‘Just look at the pots on the surrounding pages.’ This sentence, or close variations, begins three of the nine chapters in Paul Greenhalgh’s new magnum opus, Ceramic: Art and Civilisation. I imagine he’d have liked to use it in the other six, too. For the exhortation would not be out of place anywhere in this passionately written book. Where ceramic is concerned, Greenhalgh is a true believer, and he wants you to be one, too. He sees the medium as a stimulating contradiction: ‘a vibrant enabler of civilisation that doesn’t really fit into the cultural scheme of things we’ve invented for ourselves’.

That word, ‘civilisation’, is the most provocative aspect of this otherwise affable book. Its use inevitably echoes Kenneth Clark’s canon-building TV series; and even if Greenhalgh’s approach is more akin to the recent reboot of that programme (Civilisations, which aired in 2018), the book is unapologetically, unfashionably Eurocentric. Despite the implied global scope of his title, he is concerned principally with the development of ‘Western’ ceramics. The technical and aesthetic achievements of China and the Islamic world are discussed, and in some depth, but only as counterpoints and sources for European traditions.

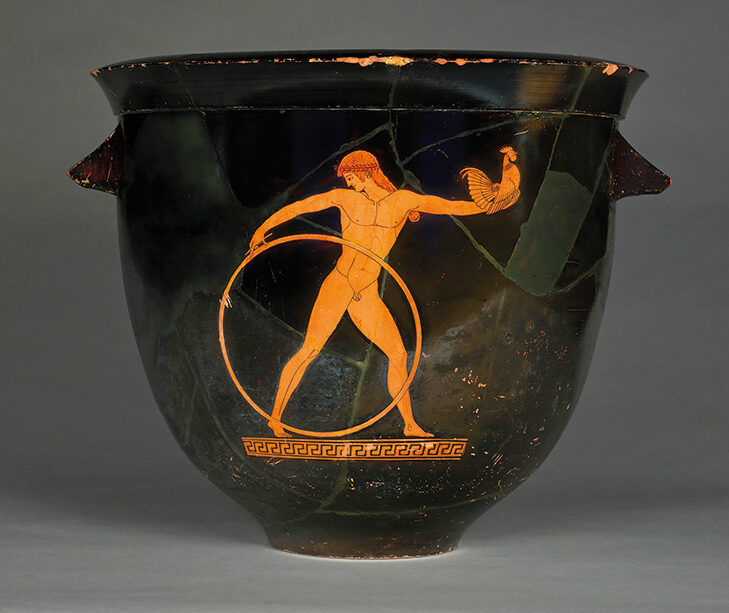

Now director of the Sainsbury Centre in East Anglia, Greenhalgh previously served in the same capacity at the ill-fated Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C., and before that, as head of research at the Victoria and Albert Museum. All along he has remained a prolific author, on topics ranging from art nouveau to world’s fairs. His narrative here begins with the red- and black-figure wares of ancient Greece. (The very word ‘ceramic’, he reminds us, comes from Kerameikos, an Athenian pottery-making district.) It ends right now, when ceramics are in the ascendancy in the fine-art world. In between, Greenhalgh manoeuvres skilfully through large-scale developments and fascinating anecdotes. At some 500 pages, the text is propelled by images, of uneven quality but impressively numerous, and often brilliantly described. Greenhalgh is a world-class phrasemaker, never more than when he has a great object in view. The vessels of the so-called Berlin Painter, active in the 5th century BC, have ‘surfaces emptied out with a dense glossy black [and] a terse, engineered, single figure planted in the middle’. On little Lydia Dwight, dead at the age of six in 1674, hauntingly captured in the then-innovative material of stoneware by her father John: ‘We can see him in our mind’s eye, eaten away, day-on-day, all the guile and cleverness in the world unable to help him.’ A Picasso vase, shaped and painted to look like an owl, is ‘so owl-like in every respect, simultaneously the staring creature sitting in the rafters of the barn, [and] the symbol, proxy and essence of Pallas Athene’.

Red-figure bell krater (c. 480 BC), the Berlin Painter. Musée du Louvre, Paris. © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée du Louvre)

No book this size could succeed on the strength of description alone, however. The best writers remember what it was like not to know everything about their field of expertise. Greenhalgh is no exception. He presents even technical matters in a simple and arresting manner. Comparing Chinese stoneware to ancient earthenware, he comments, is ‘like comparing bronze to cardboard’. But even so, ‘One’s first instinct with a good Roman red-gloss pot is to eat it. Or at least lick it all over.’ Sophistication and seduction do not necessarily run in parallel.

When Greenhalgh arrives at the key contribution of Islamic pottery – the introduction of white tin glaze, the ideal canvas for lustre or polychrome decoration – he puts the key point perfectly: these were the first wares ‘premised on glaze’, inverting the previous polarity of form over decoration. He goes on to offer a nice comparison of lustre glazes to iPads – there’s no way to tell from looking at either technology how it is achieved. ‘Thus,’ he concludes, ‘the growth of lustre in Spain came after the importation of the potters, not the pots.’

T’ang bactrian camel (c. 760), Chinese. Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City

The story of tin glaze also exemplifies the advantages of the book’s broad view. We follow the diffusion of the technology to Italy, where it made Renaissance maiolica possible; and thence to the Netherlands, where the look of Chinese blue-and-white porcelain was combined with tin glaze to produce Delftware. It is a familiar story but, even for the well-acquainted, it is useful to have it in its full context, and Greenhalgh extends the tale to less common topics, such as the growth of the French faience industry in Nevers.

As the book enters the modern period, Greenhalgh has a different problem to solve: how to help the reader navigate an increasingly fragmented, globalised industry. One passage, titled ‘Ugliness and the Era’, addresses the seeming excess of 19th-century industrial production – ‘the making of some things that are hard to explain’. Greenhalgh does, convincingly, arguing that the sudden availability of new techniques was like a rush of blood to the head, leading to complication for its own sake.

The book’s section on the 20th century is, by Greenhalgh’s own admission, its least coherent. Abandoning chronology, he explores contrasting and overlapping idioms, using capsule biographies to get the reader from one setting to the next: the American art potter Adelaide Alsop Robineau, whose pots suggest ‘the accoutrements of unknown ceremonies’; Robert Arneson, whose Funk idiom inspires a comparison to satirical comic books; Eva Zeisel, whose extraordinary life of 105 years prompts one of Greenhalgh’s most reverential passages.

It’s a bit of a scramble, but all the more entertaining for being so. Greenhalgh does offer one ordering principle for modern ceramics, framing it as a contest between functionalism and aestheticism – the legacies of Morris and Wilde. But he doesn’t labour the point, clearly reluctant to impose too clear a structure on the recent past. What comes across instead is the richness of the ceramic landscape, populated in every direction with things worth seeing and thinking about, the accumulation of several millennia’s worth of innovation.

At the end of his book, Greenhalgh writes that, ‘far more than religion, or war, or academic treatises, skill shaped civilisation’. So true, and there is no better example than ceramics. One closes this compendious history with a breathless feeling: what will potters come up with next?

Ceramic: Art and Civilisation by Paul Greenhalgh is published by Bloomsbury.

From the May 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Why are fathers so absent from art history?