The opening ceremony of this year’s Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts took place outside the ‘Swiss House’ (Svicarija Creative Centre), a large, chalet-style building in Tivoli Park with commanding views of the city and the historic castle on the facing hill. Built as a hotel in the early 20th century, it reopened recently earlier this year following a major project to restore its details and convert it into artists’ studios and residency spaces. Before then, one local told me, the ‘creepy’, run-down house on the hill was something of a no-go area. To see it open and busy at the centre of the biennial was as new to her, a long-term resident, as it was to me, a first-time visitor to the city.

Ljubljana’s biennial has been around since 1955, but a sense of novelty pervades its 32nd edition (until 29 October), which benefits not only from the added venue, but an experimental curatorial direction. There is no lead curator, and little by way of an overarching theme, to structure this year’s event. Instead, the organising committee invited the last five winners of the biennial’s grand prize to nominate a participant, who in turn would nominate another, in a series of self-selecting artists’ chains. Twenty-seven artists are taking part, their only creative guidance being to respond to the ideas and imagery in ‘Birth as Criterion’, a poem by the Slovenian writer Jure Detela after which the exhibition is named. The participants’ work is displayed throughout the Swiss House and the International Centre of Graphic Arts just a short walk down the hill, which has been the biennial’s main home since the 1980s.

This organisational method was adopted as a corrective to more heavily curated contemporary biennials. There are a few drawbacks: ‘Birth as Criterion’ features no Slovenian artists and a disproportionate number of American ones, as a perhaps inevitable accident of the selection process. Those brought in at the end of a chain had significantly less time to create or ship works – as little as a month in some cases – and as a result, some engage only superficially with Detela’s poem. (The poem itself ranges widely, from evocations of cosmic grandeur, to sensory descriptions of the body, and a condemnation of war; many exhibitors have ended up focusing on details.) But the biennial’s structure does foster a strong sense of collaboration, self-organisation and exchange that is particularly fitting for an event dedicated to graphic arts.

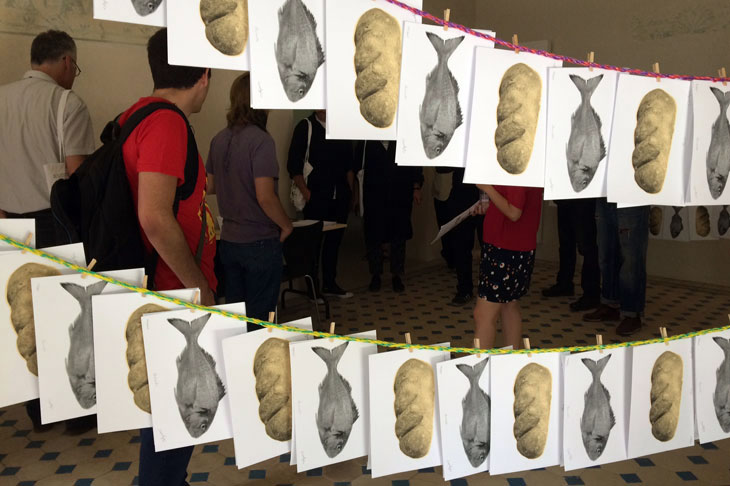

33 (2017), Mario Santizo. Photo: the author

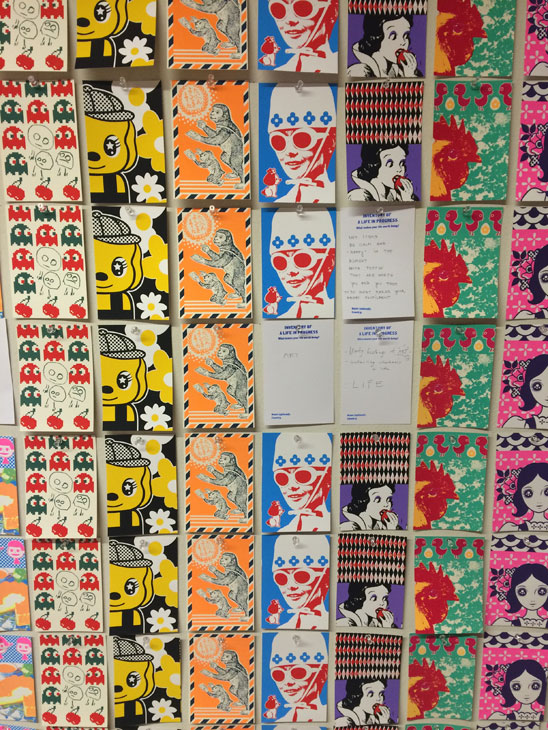

Some of the most successful contributions make these qualities explicit. Spanish artist Mario Santizo has strung prints of loaves and fishes throughout one of the Swiss House rooms. Visitors can take them home, in exchange for writing or sketching their response to the project. Upstairs, Asuka Ohsawa’s installation operates along similar lines. Inspired by one of her father’s last letters, in which he mused on the simple things that made him happy, she has plastered the walls with colourful postcards, on to which visitors are invited to jot down comparable thoughts of their own. It’s an eye-catching departure for Ohsawa, who usually makes artists’ books, and only came about, she tells me, because of the generous space and technical assistance that this relatively small yet established biennial can offer.

Inventory of a life in progress (2017), Asuka Ohsawa. Photo: the author

Language features prominently in the exhibition, as artists respond to both Detela’s poetry and the traditions of graphic art and design. Michelle Andrade, for example, has painted a line from ‘Birth as Criterion’ directly on to the wall in bright, graffiti-like bubble text. ‘Here I am, smaller than I ever was,’ in this context, seems less of a musing on mankind’s cosmic insignificance (as Detela meant it) than a statement drawing attention to those who are marginalised from, or choose to reject, mainstream and ‘sanctioned’ forms of visual culture.

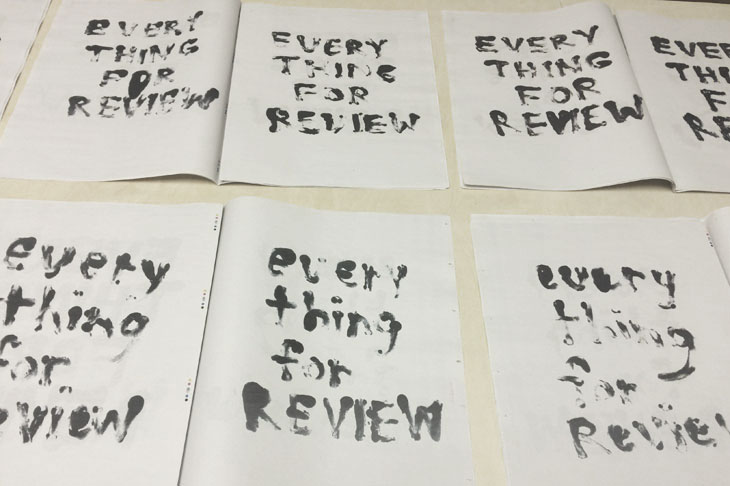

Reviewing the Review, Everything for Review (2017), Jennifer Schmidt. Photo: the author

Jennifer Schmidt’s installation, Everything for Review, is inspired by Dieter Roth’s ‘Review of Everything’, a journal that printed all images and texts submitted to it from 1975 to 1987, by which point it was receiving too much content to be publishable. Among the stacks and piles of newsprint sheets in Schmidt’s display are numerous renditions of the work’s title, rendered in monotype. The artist applied the ink for these by hand onto the plates, leaving smudges and fingerprints visible – a method that, like Roth’s experiment, collapses the usual filters between the people making and distributing printed matter, and those consuming it.

Ljubljana has its own lively zine and self-publishing community, which has its roots in the proliferation of underground printing houses that sprang up during the Second World War and persisted under Soviet rule. But it has been a long time since the biennial confined itself purely to the graphic or printed arts, and this year’s exhibition encompasses performance, video, sculpture, animation and painting as well.

Carlos Monroy performs outside the International Centre of Graphic Arts, Ljubljana

Carlos Monroy’s series of videos, in which he dons devil-like carnival outfits from various countries, and performs their attendant folk dances alone in the streets of Ljubljana in the dead of night, are a highlight. So are the works of Jarrett Key and Jelsen Lee Innocent, both New Yorkers, who explore how black identity and methods of resistance have been passed down through generations. Key creates his performative ‘hair paintings’ to a soundtrack of his family’s recollections of his grandmother, while Innocent’s powerful sculptural installation evokes the fences and pickets that have structured black experience throughout modern history.

Pickets of Purpose for The People of Perpetual Protest (2017), Jelsen Lee Innocent. Photo: the author

At the centre of all these works is a sense of how potent creativity can be as a means of communication – how art can bring communities together when official methods fail. Because this belief also underpins the structure of the show, ‘Birth as Criterion’ feels surprisingly coherent for something so self-consciously un-curated. Additional exhibitions throughout the city expand on the ideas raised by the main displays: Kresija Gallery presents ‘The Void’, a print portfolio made with five of the exhibiting artists that reflects on the relationships and friendships resulting from the project. ‘THIS IS NOT A NAME’ at Skuc Gallery ties the experimental structure of ‘Birth as Criterion’ more closely to Detela’s poetry and his flexible approach to language and form.

Jarrett Key at the Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts. Photo: the author

But the best of these secondary events is Maria Bonomi’s solo exhibition at Jakopic Gallery. The Brazilian artist and activist is a long-term supporter of the biennial and a strident champion of printmaking as a radical, democratic form of art. Her abstract woodcut works are extremely powerful: in one, a rising column of red ink cuts through incised black lines in a disturbing evocation of political violence. In her tour of the display in the opening week, she summed up something of the spirit of this determinedly experimental biennial. ‘Print is a form of communication and also revolution,’ she explained. ‘It is a conversation.’

The Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts continues until 29 October 2017.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

What happens when an artist wants to be anonymous?