Regentesses of the Old Men’s Almshouse (c. 1664) by Frans Hals is, at first glance, an unassuming work, lacking the rigour one might expect from a formal group portrait of the period. Arranged around a table, the Regentesses are aged and slightly stiff, but have florid complexions that seem eerily lifelike. As we return their watchful gazes it is as though we too are among them. The painting’s lack of finish was later attributed to the artist’s infirmities – it was completed two years before he died; the French critic Eugène Fromentin went so far as to describe the painter’s condition during its creation as ‘three-quarters dead’. ‘Frans Hals and the Moderns’ at the Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem, however, does not encourage us to consider the artist’s psyche, wellbeing or even artistic motives. It focuses only on how Hals was perceived by others.

Regentesses of the Old Men’s Almshouse (c. 1664), Frans Hals. Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem Photo: René Gerritsen

It is 150 years since the French journalist Théophile Thoré rescued Hals from his reputation as a peripheral painter and a debauchee. Describing Regentesses in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts in 1868, Thoré wrote, ‘The life-size figures modelled in broad, flamboyant strokes, protrude out of the frame in relief. It is beautiful and almost frightening.’ For many it was a revelation. The largest collection of Hals’s work, open to the public in the attic of the city hall in Haarlem, became a site of pilgrimage for artists, among them Fantin-Latour, Monet and Cassatt; those represented in the exhibition include Courbet, Manet, Whistler, Sargent, Liebermann – and William Merritt Chase, who made an annual visit.

Regentesses was held in particularly high esteem; elements of the painting reappear again and again in the work of Hals’ imitators. Sargent’s study of the two rightmost figures hung in his studio until his death. When Whistler arrived he asked for a set of small stairs so he might touch their faces. A copy by Manet has recently been recovered. The Frans Hals Museum makes best use of its modest space to convey Hals’s influence on late 19th-century artists not by making relentless comparisons on a grand scale, but through a close analysis of the practice of copying. The first few rooms address this as a literal act but later on it is presented as a more abstract encounter, as each painter reimagines Hals in a way that reflects their own ambitions.

Portrait of a Woman (1878), William Merritt Chase. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut

One aspect of Hals’ style that they seized on was his bravura brushwork – a bold touch that leaves a light, ephemeral impression. His unblended application of colour can seem crude at close quarters, but from afar it dissolves into endless nuance. The Impressionists were particularly keen to emulate the effect and, without relying on mechanical reproduction, copying was a way to survey a work’s surface and savour every stroke. The result was a highly personal souvenir of each artist’s communion with the work. Photographs from the period cover the walls of the museum’s adjoining rooms, one recording a row of easels against walls densely packed with paintings. It conveys an experience far more informal and immersive than our own.

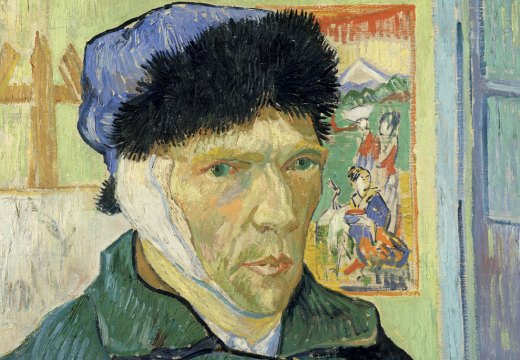

Van Gogh, who apparently revered Hals to a greater extent than is usually acknowledged, admired how he ‘dashed off a thing […] and did not retouch it so very much’. That he was wrong – Hals built up layers of paint, each of which needed time to dry – does not detract from the revelation that ‘the best pictures […] seen from nearby are but patches of colour side by side, and only make an effect at a certain distance’. This suggests the entertaining image of Van Gogh darting back and forth before the works, mesmerised by the way in which they zoom in and out of focus. The tangle of lines comprising the sitter’s limp, drooping hands in Postman Joseph Roulin (1888) explicitly recalls the gaunt extremities of the figures in Regentesses.

Postman Joseph Roulin (1888), Vincent Van Gogh. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

When Sargent visited the city hall in Haarlem in the summer of 1880 he lost track of time, staying a week longer than planned. His copies are tellingly inexact; presented beside the original work we can see how they are darker and more loosely rendered. Rather than duplicate Hals, he had hoped to capture the painter’s essence. Sargent’s success as a portraitist was in part due to his inventive compositions, which imbued the subject with a surreptitious psychological presence without resorting to symbolism. Take, for instance, his portrait of Constance Wynne-Roberts (1895), which casts her as a sophisticated but sincere and warm figure. The sense of character conveyed here echoes Hals, whose subjects are often spirited or, at the very least, sympathetic.

Also in the exhibition is a series of large-scale cartoons depicting seedy streets in 19th-century Haarlem in an attempt to indicate what the city was like at the time. For 19th-century realists, Hals’ interest in depicting typical Haarlem scenes and people merged into their wider meditations on modern life. The museum pairs Hals’ Malle Babbe (1630–35) – an ambiguous, affectionate depiction of a mentally ill local figure that evades easy categorisation – with a near identical copy by Courbet. For the French painter, Hals’ candid depictions were emancipating, the Old Master authorising a modern’s desire to record the everyday.

Constance Wynne-Roberts, Mrs Ernest Hills of Redleaf (1895), John Singer Sargent. National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

A rather less well-known artist, the American painter Robert Henri, spent what would today be an artist’s residency in Haarlem, during which he lived out a Halsian existence and painted local citizens. Hals had a gift for portraying children and among Henri’s subjects is The Laughing Boy (1910), an image of innocent elation. The sitter was recently identified as an urchin named Jopie van Slouten; the publication accompanying the exhibition recounts his life in considerable, perhaps unnecessary, detail, in an attempt to show how integrated artists were in ordinary Haarlem society.

All of the painters in this exhibition seem to have recognised a certain spontaneity and daring in Hals’ work, forging an affinity with the Haarlem painter that collapses linear assumptions about style. In 1883 a Belgian journal declared: ‘Frans Hals, c’est un moderne.’ Hastily reframed by the enthusiasm of the moderns, Hals existed anew.

‘Frans Hals and the Moderns’ is at the Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem until 24 February 2019.

From the December 2018 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?