Last year almost every museum and gallery in the land focused on the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War. Pallant House Gallery, however, had the bold idea of honouring another but related conflict: the Spanish Civil War. The British artists of the First World War are well known, and the Second World War had its roll call of official war artists, but as far as the UK is concerned the Spanish Civil War was ‘the poets’ war’, to borrow Stephen Spender’s term. British and Irish writers including W. H. Auden, David Gascoyne, John Cornford, Sylvia Townsend Warner, Julian Bell et al) were stirred to fight or write in support of one or other faction in this bitter conflict.

In fact, as this thoughtful exhibition reveals, many British artists were similarly moved. Some, such as landscape painter Wogan Phillips, artist Clive Branson and sculptor Jason Gurney, joined some 40,000 men and women from 53 countries in the International Brigades, fighting for the democratically elected Republican government against General Franco’s Nationalist rebels. Some, including the artist Felicia Browne (the only female British combatant, whose strong, dynamic drawings of fellow militiamen and women feature in the show), lost their lives. Many others used their art to raise public awareness in Britain of the plight of civilians in Spain, and to express their own anguished response to the events unfolding there. Among them were the extraordinary Surrealist printmaker and painter S. W. Hayter; the artists Eric Ravilious and Edward Burra; sculptors Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore; and the teenage prodigy Ursula McCannell, who used Robert Capa’s photographs of refugees, published in magazines such as Picture Post, as source material for her poignant paintings.

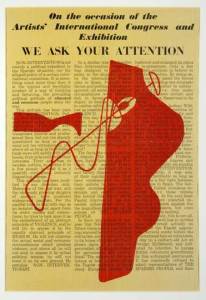

Design for ‘We Ask Your Attention’, Henry Moore. Published by the Farleigh Press, 1938. Reproduced by permission of the Henry Moore Foundation

As the gallery’s artistic director, Simon Martin, explains in the Pallant House magazine, Britain was officially neutral. But for many British artists and writers, the local conflict between the Republicans and Franco’s insurgents was emblematic of a much greater Europe-wide battle between radically opposed ideologies. It offered an apparently clear confrontation between democracy and various forms of fascist authoritarianism, however complicated by atrocities on both sides, and stimulated the political and social conscience of a whole generation of artists.

This exhibition offers a correspondingly eclectic mix of materials, ranging from documents of purely historical interest to major artworks that transcend their context absolutely. Here there is no art for art’s sake. There are political posters, political cartoons, prints, photographs, props for political rallies, textiles, book covers, sculptures and paintings, reflecting how deeply the conflict and the ideological passions it aroused penetrated all aspects of visual culture.

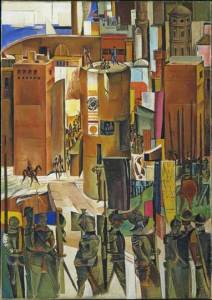

The Surrender of Barcelona (1934–7), Wyndham Lewis. Photo © Tate, London 2014 © the Estate of Mrs G. A. Wyndham Lewis

What is immediately striking moreover is the variety and complexity of response. Clive Branson, a communist, painted factory workers in Battersea buying the Daily Worker and taking part in demonstrations, explicitly linking events in Spain with the greater struggle of world revolution. Frank Brangwyn, also pro-Republican but a devout Catholic, based his poster, SPAIN, which calls for non-partisan aid to women and children in Spain, on the conventional iconography of the Madonna and child. Among the many responses from English Surrealists (who rallied mostly to the Republican cause) is S. W. Hayter’s Paysage Anthropopage (1937), which draws parallels between the contemporary violence in Spain and the destruction of the ancient Roman city of Numancia.

Meanwhile Wyndham Lewis, a critic of communism, pointedly invoked the 15th-century Siege of Barcelona – in which John II of Aragon crushed Catalan constitutionalists – in his coolly geometric Surrender of Barcelona (1934–7) commemorating the fall of the city to Franco’s troops. Perhaps the most prodigious artworks are the macabre, indecipherable images of Edward Burra, who had witnessed horrifying violence at the opening of the war and remained ambiguously aligned. But John Armstrong, far less well known, is a great rediscovery. His intense, enigmatic architectural images of destroyed buildings, the wallpaper still flapping, offer haunting evocations of loss and destitution.

At this traumatic period in European history, the exhibition suggests, the public turned actively to art as both witness and a source of understanding. The works of Henry Moore, F. E. McWilliam and Merlyn Evans reveal the immediate impact of Picasso’s Guernica, which toured through Britain in 1938/9. In 1938 the Victoria & Albert Museum exhibited, controversially, a set of Goya’s Disasters of War prints, which are displayed at Pallant House alongside Burra’s marvelous The Watcher. The final room, containing works by R. B. Kitaj and Ron King, reveals how the political passions aroused by the Spanish Civil War have continued to reverberate in subsequent British art. This is a fascinating exhibition – an illuminatingly rich weave of history, art and visual culture.

‘Conscience and Conflict: British Artists and the Spanish Civil War’ is at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, until 15 February.

Related Articles

Talk: ‘Modern Figures: The Body in Contemporary British Painting’ at the London Art Fair (featuring Simon Martin, artistic director at Pallant House)

12 Days: Simon Martin’s highlights of 2015

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

What would Jane Austen say?