What does the opening of the Met Breuer mean for the display of the Met’s modern and contemporary collections? How does it fit in with the brief you were given when you were appointed in 2012?

My recruitment by Tom Campbell [the director of the Met] was not to replace the existing position exactly, but to expand it, both geographically and historically. So that has to be brought to bear on the shaping of the collection and the installation.

I should perhaps correct an assumption that the collection will be transferred lock, stock and barrel into the Breuer Building. The Breuer was linked to our plans, already determined by the trustees, to build a new wing for modern and contemporary art at the main building at the Met. So these two projects were in tandem with one another.

How have you approached the programming? And how does the modern and contemporary department relate to the rest of the museum?

What I proposed after I arrived and I’d had some time to take stock, was to have a programme of temporary exhibitions that would allow us to do a number of things. Firstly, to do the kind of show that we are doing with ‘Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible’, which draws on the historic collection; secondly, a programme that would reflect the diversity of the collections at the Met. So through the programme and through the parallel collecting strategy that I established when I arrived, we would build up a collection of work that responded to, but took a very different pathway from the Asian department, the Islamic department, the African department, the Oceanic department – but all in conjunction with colleagues from those departments.

We are solidly based in the 20th and 21st century: my background and the expertise and experience of every single member of my team comes out of this period. But the richness of the programme we can present at the Breuer can be seen in shows like ‘Unfinished’, which brings all of our colleagues together round a table, where we can demonstrate what we can do in the context of an encyclopaedic museum.

You began your career in the Breuer building, when it housed the Whitney. What is it like to work there now?

I was on the Independent Study Programme, which is a postgraduate fellowship that the Whitney still runs, but in those days it had eight art historians and eight artists, who were selected from an international submission. We were able to come up with ideas for exhibitions – for the public – and bring in all sorts of works, if we could manage to borrow them.

It was a building where there were still offices on the top floor, the staff was much smaller, and where Tom Armstrong [then director] had a terrace outside his office where he would grow tomatoes. The Met is at an advantage in having its central services back at the main building, so we can really work with the galleries as they are – we’ve been buffing them up over the last couple of months.

Can you explain why you chose Nasreen Mohamedi as one of the two opening exhibitions?

‘Unfinished’ focuses on the Western tradition of painting and sculpture, because it reflects the collecting history of the Met in those media. It was important, nevertheless, to stage an exhibition of an artist who has made an enormous contribution to the history of modernism in its international context. I’ve known Nasreen Mohamedi’s work for a long time – I love it. It involves the essence of art-making in that it’s an exhibition about graphic work, but it has another narrative as a corollary – that of photography, which she didn’t show in her lifetime as art.

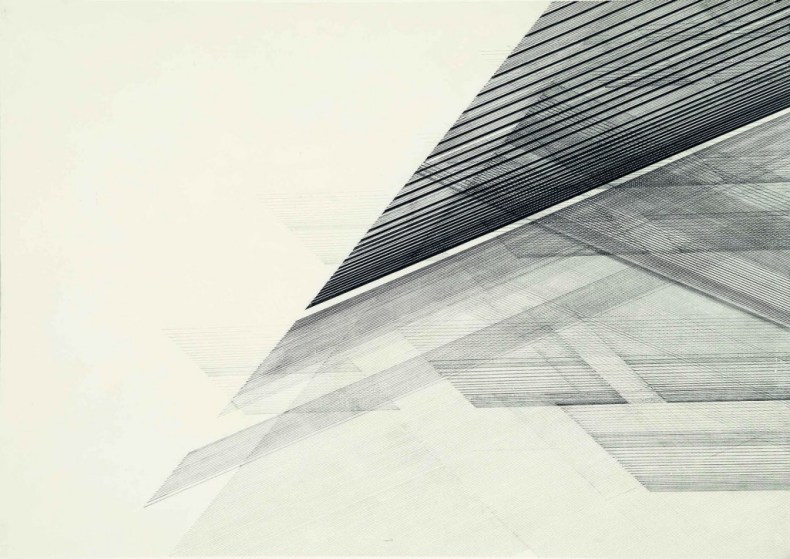

The show is a counterpart to ‘Unfinished’ in many ways, but it is more specific in its relationship to the architecture of the building. Mohamedi starts in her mature period with the grid; the Breuer building is built on the grid. The exhibition installation uses as its cue the ceiling grid, although this won’t be apparent to most visitors – but it’s an important aspect for me to pay respect to the building with one of the opening shows. From the reproductions it is impossible to understand the texture [of the work] and there is a kind of sensuality about it. The Breuer building is rich with texture and colour, and you realise what an amazing sensualist [Marcel] Breuer was. And that’s what the Mohamedi show reflects to some extent.

What is the thinking behind the artists’ commissions?

The point is that the artists deal […] with the real meaning of the encyclopaedic museum. We’ve asked Kerry James Marshall to make a selection on one of the floors of his show [in October], and that will be an artist’s view of the Met. It goes from furniture to artefacts, from African and Oceanic to some pretty amazing 17th- and 18th-century European and American paintings.

And how are you going to add to the modern and contemporary collections?

We’re working with artists on a different kind of programme, which I’m going to launch in September. That will be a much more light-footed programme, which will hopefully feed into our collection in terms of gifts, or some kind of long-term commitment to the Met. This will allow us to represent a number of artists across the world, without whom we cannot tell a history of art in the 20th century effectively.

We cannot cover an encyclopaedic story of the world – we’re not in a position to do that. But we are in a position, through the expertise-collective that is the Met – I cannot emphasise enough how brilliant it is working with scholars of different periods – to decide who those great artists are and to work towards an appropriate and deep representation of their work. That’s the way that I feel we should be going – and that is the way we are going.

The Met Breuer opens on 18 March.

‘Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible’ runs from 18 March–4 September;

‘Nasreen Mohamedi’ runs from 18 March–5 June.

From the March issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘He wasn’t edgy. He was honest’ – on the genius of David Lynch