There are few fans of Donald Trump among the management and boards of New York’s cultural institutions. Personal distaste aside, they are the beneficiaries of the trends that President-elect Trump has railed against: globalisation, and the unequal distribution of wealth that it has pulled in its train. They have been served well by the policies pursued from Bill Clinton’s presidency onward, of the liberalisation of trade and financial deregulation – policies that Donald Trump identified so forcefully during the election as responsible for the assault on middle America that he (ostensibly) and his voters (genuinely) wish to reverse.

While New York’s financial, real estate, and business elites may be accommodating themselves to the prospect of a president who will soft-peddle on banking regulation, they are equally discomfited by one who could stoke inflation through pursuit of an irreconcilable combination of tax cuts and public expenditure increases, or scapegoat them in a single late-night tweet. Meanwhile, Trump has declared war on the New York Times, the house newspaper of New York’s cultural and social elite, as the Times has on him. There is therefore an entrenched culture war developing that could make that of the George H.W. Bush years look like a playful skirmish. How then are New York’s great museums of art likely to fare financially during the next four years?

Federal funding itself is not a significant line item for these institutions, and the Obama administration was never very enthused by high culture. In recent years, there was nothing like the welcome for the established cultural icons, institutions, and art forms that was extended under, say, President Kennedy. At city level things are already difficult. The three-term Bloomberg administration prioritised high-profile, expansionist cultural institutions – most of which are in Manhattan. Bloomberg helped capital projects through direct funding and through zoning regulations to incentivise developers. His private philanthropy worked in tandem with his priorities as mayor, and together this constituted an impressive, focused arsenal of cultural support. You could cavil at specific decisions but the cumulative impact was incontestable.

The de Blasio administration differs in three respects. Firstly, it does not have Bloomberg’s philanthropic follow-through. Secondly, it is less obviously competent than its predecessor, so the impact of policy is simply more attenuated across the board, cultural policy included. Thirdly, the strategic framework through which it views culture is broadly around social access and equity rather than branding and global resonance. It therefore tends to be more engaged with smaller organisations, often in the outer boroughs. This makes the City of New York in the current administration less of a player in the future of the major Manhattan-based museums than it has been for some time.

What about trusts and foundations? Many of the more established national foundations – Ford, Rockefeller, Pew, Gates etc. – are edging politely but firmly away from what they now call ‘legacy’ institutions that cannot demonstrate a significant contribution to solving or soothing specific social or economic traumas. A museum educational programme in a socially disadvantaged area may get a look in, but the heavy grind of helping with a museum’s operating budget is no longer a priority for most – especially if the museum is a few thousand miles away from the West Coast communities where many of the newer foundations are located.

Meanwhile, corporate philanthropy shrivelled up in parallel with the intensifying search for shareholder value in the 1990s and early 2000s. Corporate funding is accessible if and insofar as a cultural institution can demonstrate – with robust metrics – the contribution that sponsorship makes to the sponsor’s bottom line. This can be tough territory for the arts. There are therefore three other critical sources of income support: endowment, earned income, and individual philanthropy.

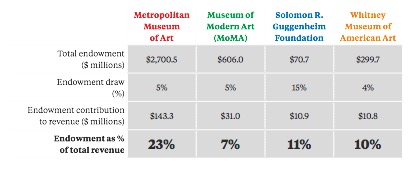

Source: 990 forms 2014. Note: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation drew approximately 4.2 per cent from temporarily and permanently restricted endowment funds; additional spending came from unrestricted board-designated endowment funds.

Endowment

The endowments of the Metropolitan Museum of Art ($2.7 billion); the Museum of Modern Art ($606 million); the Whitney Museum of American Art ($300 million); and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation ($71 million) generate respectively, depending on the draw policy – usually set at around 5 per cent – some 23 per cent, 7 per cent, 10 per cent and 11 per cent of their total annual operating revenue. Their contribution to the annual budget is helpful but, with the exception of the Met, not decisive. The crash of 2007–08 underscored to endowment managers for museums and universities the challenges of a business model based on endowments that are volatile when the world is volatile. The next president’s term is quite likely to be a prolonged period of volatility, global retrenchment, conservative investment strategies, and cash-holding – and therefore lower returns.

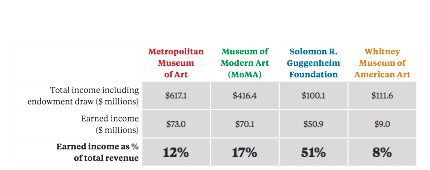

Earned income

Table Two shows earned income in absolute and percentage terms for the Met, MoMA, the Whitney, and the Guggenheim. This comes from admission charges or, in the case of the Met, ‘recommended contributions’ – voluntary donations in lieu of admission charges, the description of which was recently challenged and as a result refined in a court case – and from catering, facility rental, retail, and some rights income.

The percentages are modest as a percentage of the total, although higher in New York than elsewhere in America because New York museums enjoy some 58 million tourist visits each year. The Guggenheim is the outlier here, with higher earned income in both percentage and absolute terms than its peers. When tourism flags for the Guggenheim – for example after 9/11 – the impact is immediate. The Guggenheim’s earned income also includes some $12 million in programme collaborations – franchise and related fees, a critical element in its business model. The business model is closely tied to wider trends in the global economy.

Source: 990 forms 2014

Individual donors

So back to individual donors. The great museums of New York are highly dependent on the benevolence of the 1 per cent to 0.1 per cent of wealth-holders, combined with the tax deductibility of their generosity. On the critical role of the tax regime, we need to watch carefully how the so-called ‘Senator Grassley’ agenda – the senior senator from Iowa – will fare under President Trump. Grassley questions persistently and persuasively the legitimacy of tax privileges for organisations whose beneficiaries are already well above the median tax payer, such as museum visitors.

The withdrawal of tax privileges for museums could prove an irresistible weapon in any recrudescence of the culture wars, especially as the president-elect has no record of interest in the stewardship of material culture, scholarship (witness Trump University), community engagement, or any of those things that are the last resort of the museum director under pressure to legitimate their institution’s tax status.

The long-term viability of New York’s major museums is therefore significantly dependent upon the willingness and ability of their boards to underwrite them. These boards have been willing and able to do so for three reasons: their fabulous wealth, which is why they are sought as board members; the tax regime under which their support is organised; and the social legitimacy and standing they accrue from their philanthropic efforts. These factors have driven them towards a broadly energising and expansionist agenda.

The Met, of course, has taken out an eight-year lease on the Whitney’s Breuer building on the East Side. This is part of a complicated shuffle, arranged in large part to accommodate the wishes of Leonard A. Lauder, former chair of the Whitney and recent donor to the Met of an unparalleled collection of cubist and modern painting, valued at over $1 billion. The Met is also planning for a David Chipperfield-designed extension of the southwest corner of its main building on Fifth Avenue. Meanwhile MoMA is engaged in a Diller Scofidio + Renfro-designed expansion that includes an increase in gallery space by one third. International growth via franchises has been the Guggenheim Museum’s basic modus operandi since the success of Bilbao – most recently with a bumpy reception for (and eventual rejection of) a franchise in Helsinki. The Whitney moved to its new, enlarged home in Chelsea, designed by Renzo Piano, in 2015.

Earlier this year, however, the Met also announced a dramatic course correction: high-profile voluntary and compulsory redundancies to address a loudly advertised underlying structural deficit; the reversal of a trend of heavy investment in the expansion of the digital domain; and a slow-down of the Chipperfield project. The immediate budgetary shortfalls were modest for an organisation with an endowment of $2.7 billion – only around $10 million over a year – although the stated trend line of growing annual deficits was more ominous. The explanation offered was incremental staff costs growing faster than income. The lease taken out on the Breuer building, and associated costs, were explicitly excluded from the explanation as they are met directly by… board philanthropy. That is of course exactly the point: there is more pressure than before on a narrow constituency.

MoMA also announced some layoffs at around the same time, and these were linked in some commentary to the Met’s challenges. However, they are more likely related to the senior management’s changing sense of its needs. Painfully for the Met, its announcement of retrenchment coincided with MoMA’s announcement of a gift of $100 million from entertainment mogul David Geffen. The gift is for general operating and reserves, not capital – the holy grail of fundraising, as it can be used at the discretion of the institution to fund areas of activities that are toughest to raise. The scale and focus of MoMA’s development strategy and director Glenn Lowry’s skill in managing and encouraging his board’s philanthropic impulses (i.e. ‘managing up’) remain formidable.

The Whitney has tripled the size of its building to 200,000 square feet and although its visitor numbers have increased, the burden of annual fundraising has also increased more than commensurately. The board here appears content to put its collective shoulder to the wheel, enthused by the overwhelmingly positive reception given to the move, the building, and the exhibition programme. The main risk is longer-term donor fatigue. The Whitney also has the prospect of receiving back on to its books the Breuer building, if it proves too expensive for the Met.

So the outlook for New York’s largest art museums is a little unsettling. A Trump presidency is anxiety-inducing not because of any direct financial impact, but because of its potential impact on the world economy, and therefore on New York philanthropy and tourism. Perhaps more significantly, a culture war between scapegoated elite liberal and humanities institutions and a populist presidency seems likely. This climate may in turn affect both their overall appeal to the narrowing band of philanthropists and put at risk the fiscal privileges they enjoy under section 501(c)(3) of the federal tax code.

The sides of ‘pyramid of giving’ for culture grow ever steeper and the funding base narrower. New York’s large art museums will need to rally – and will probably succeed in rallying – that small group at the top, and keep it on side. But the maintenance of the formidable development apparatus they have created for this purpose has a high opportunity cost, in the time, money, and the emotional reserves of board, management, and staff. The longer-term risk of continued expansion in this environment is that institutional momentum – the sine qua non of successful fundraising – becomes the mission itself.

Additional research for this article was by Antoni Durski (AEA Consulting).

From the January 2017 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Cultural leaders must resist being brought into line