Marking the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth, this display includes handwritten scores and period instruments to show how he composed key works. Through prints and paintings it also looks at the changing society in which his music was performed. Find out more from the Bundeskunsthalle’s website.

Preview the exhibition below | View Apollo’s Art Diary here

Masked ball in the Bonner Hoftheater with musicians and dancers (1754), François Rousseau. Photo: Horst Gummersbach; © UNESCO-Welterbestätte Schlösser Augustusburg und Falkenlust Brühl

François Rousseau of Bonn was court painter to the electors of Cologne in the decades before and after Beethoven’s birth in the city in 1770. This painting, with its typically illusionistic rendering of space, shows a masked ball in the court theatre of Bonn – the kind of aristocratic scene which, the exhibition contends, would gradually come to be replaced during Beethoven’s day by public opera and concert halls, reflecting the rise of the middle classes and the corresponding growth of popularity in orchestral music.

Paper theatre with a scene from Beethoven’s opera Fidelio, first performed in 1805. Photo: © Peter Schauerte-Lüke/Burgtheater

Beethoven moved from Bonn to Vienna in 1792, initially establishing a reputation as a virtuoso pianist in the salons of the nobility, before the wildly successful performance of his First Symphony in 1800 established his reputation as Mozart’s heir. In 1803, he was appointed composer-in-residence at the Theater an der Wien – a new, lavishly built venue, at which his Second Symphony received its premier in 1803. This paper theatre – a form of entertainment popular in the early 19th century, sold at performances as souvenirs – depicts a scene from Fidelio, the composer’s only opera, which premiered at the Theater an der Wien in 1805.

Quartet of string instruments (1820), Franz Geissenhof. Photo: © KHM-Museumsverband

Sometimes called the ‘Stradivari of Vienna’, Franz Geissenhof was the leading luthier during Beethoven’s day. As the city became the focal point of music on the Continent, Geissenhof adopted and adapted the Italian model for string instruments. This quartet, featuring a rare example of a Geissenhof cello, was made in 1820 – when Beethoven was working on his Missa Solemnis.

Large ear trumpet (1813), Johann Nepomuk Mälzel. Photo: © Beethoven-Haus Bonn

By 1811, Beethoven’s hearing had deteriorated to a point of almost complete deafness, and he had ceased all public performances – though he continued to compose. This ear trumpet was made for him by the inventor Johann Nepomuk Mälzel, with whom Beethoven put on several concerts – Beethoven’s music performed by Mälzel’s musical automatons – before the composer initiated legal action against him for staging unlicensed performances of Beethoven’s work.

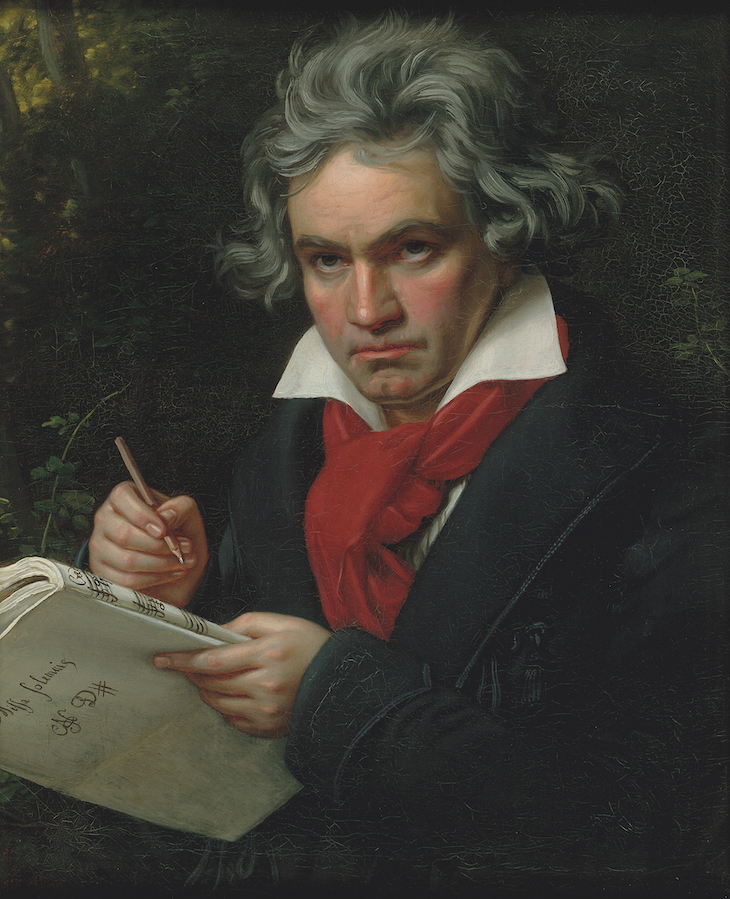

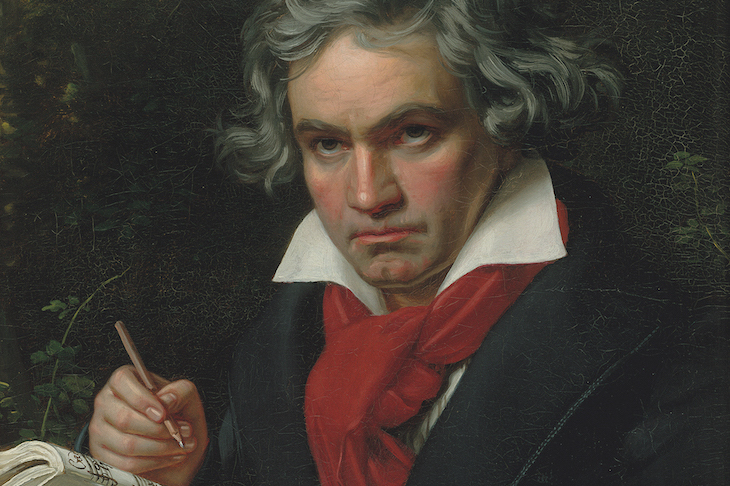

Beethoven with the manuscript for Missa Solemnis (1820), Joseph Karl Stieler. © Beethoven-Haus Bonn

This famous portrait depicts the composer working on his Missa Solemnis – his last great choral work, completed in 1823, which preceded his Ninth (and final) Symphony. It is said that the artist, Joseph Karl Steiler, had to paint the hands from memory, since the composer refused to sit for his portrait any longer.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

How to give back looted objects