The French architect Jean Jacques–Lequeu is best known for his meticulous, visionary drawings of imaginary cities. This major exhibition of works from the National Library of France explores these architectural fantasies, as well as the inward-looking works he created in later life. Find out more from the Petit Palais’s website.

Preview the exhibition below | See Apollo’s Picks of the Week here

Hôtel Montholon. Projet de salon (1786), Jean-Jacques Lequeu. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

Born in 1757 in Rouen, Lequeu trained initially as an architect in Paris before the French Revolution. However, the Hotel Montholon in Paris, built by Francis Soufflot in 1785, is one of the only real buildings on which Lequeu is known to have worked; a number of his drawings on the project survive, including this design for the salon.

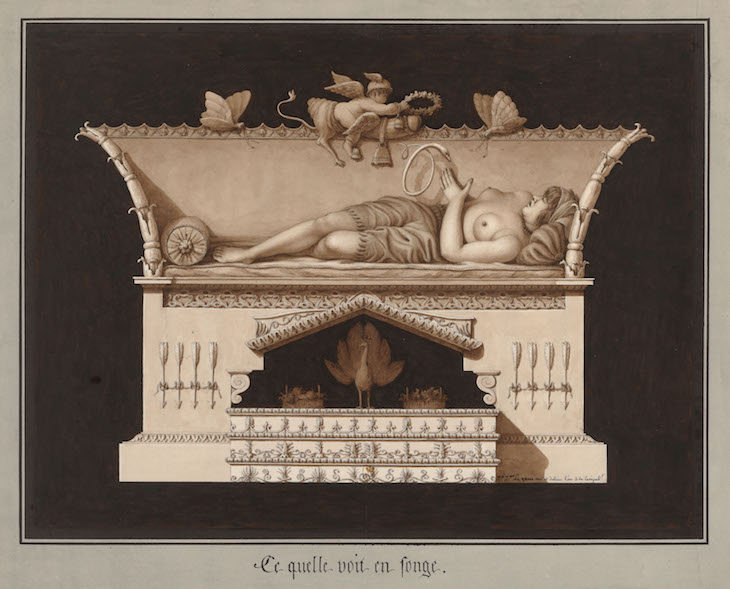

What she sees in her dreams (n.d.), Jean-Jacques Lequeu. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

After the revolution, Lequeu was employed in various government offices as a draughtsman – but he also began to produce a series of bizarre architectural fantasies, for a vast project he named Architecture Civile, and erotic drawings. Works such as What she Sees in her Dreams combine the two; it is difficult to determine whether the half-nude figure is reclining on a chaise longue, dreaming the scene around into existence, or positioned like a pediment sculpture atop a temple.

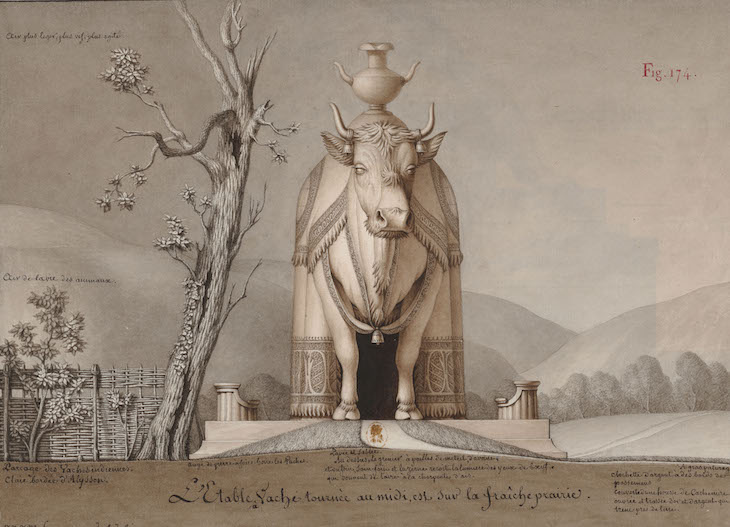

The cowbarn, turned to the south on the fresh meadow (1777), Jean-Jacques Lequeu. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

Alongside his contemporaries Claude-Nicolas Ledoux and Étienne-Louis Boullée, Lequeu has been considered as a practitioner of ‘visionary architecture’, which imagined a mode of building that could do away with the allusive nature of architecture since the Renaissance, installing in its place a kind of structure that referred directly to its function. One of Lequeu’s best-known works, accordingly, is this design for a cow shed in the form of a giant cow.

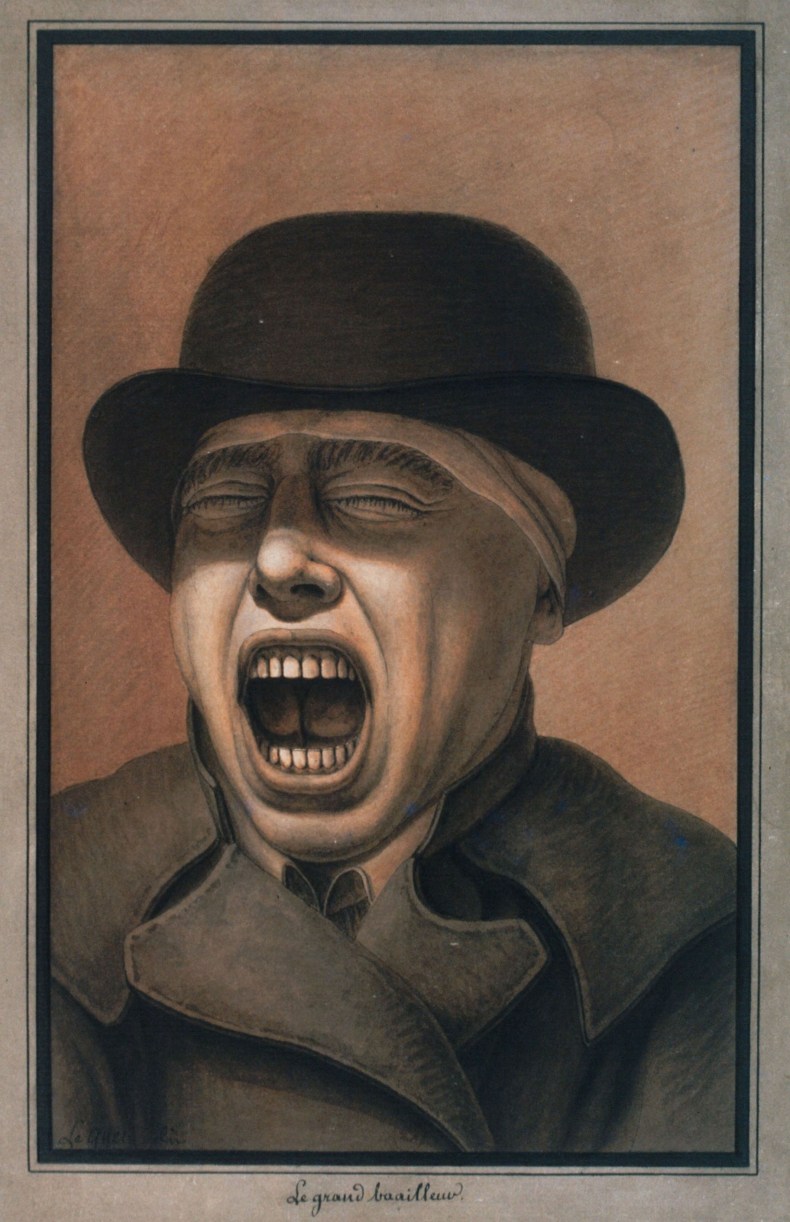

The great yawner (before 1825), Jean-Jacques Lequeu. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

In the later part of his life, during which time Lequeu lived above a brothel, the artist seems to have become increasingly mentally disturbed, producing a number of psychologically charged drawings such as this. Six months before he died in obscurity, the artist donated several thousand drawings to the National Library of France, securing his legacy as one of the most compelling and singular architects in history.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

How to give back looted objects