From the Loewentheil Collection

The Stephen Loewentheil collection of early photographs of China is the largest in private hands, with some 15,000 works by Chinese and international artists. For this exhibition, the first photography display at the Tsinghau University Art Museum, a selection of 120 photographs offers a glimpse of late Qing dynasty China. Some of the earliest photographs of the streets of Beijing are shown alongside depictions of the Old Summer Palace and rural monasteries. There are also views of the Great Wall and the Min River, and portraits of various figures in 19th-century China’s diverse society, from politicians and generals to merchants, actors and students. Find out more from the Tsinghau University Art Museum’s website.

Preview the exhibition below | See Apollo’s Picks of the Week here

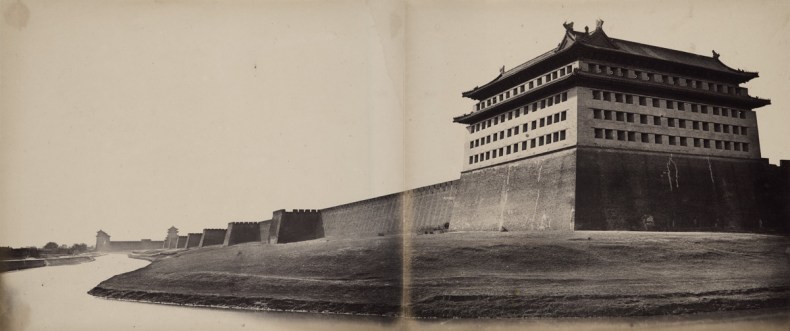

North Gate, Beijing (1860), Felice Beato. Courtesy the Loewentheil Collection

One of the world’s first war photographers, Felice Beato was sent to China in 1860 to document the Second Opium War. He disembarked in Hong Kong, and the record he immediately began to keep of his surroundings comprises some of the earliest photographs taken in China. This photograph shows a corner tower on the north side of Beijing’s Ming Dynasty city wall, which was completed in 1553, and which has since been largely demolished.

Hong Kong Harbour (1870), Lai Afong. Courtesy the Loewentheil Collection

Europeans began to establish photography studios in China’s major coastal cities from the 1850s. The Chinese soon followed: Lai Afong opened his studio in Hong Kong in 1859; he would become the country’s most significant photographer of his day, with a style influenced by literati painting as well as the Western landscape tradition. This image, which extends over three prints, depicts the Hong Kong harbour in 1870.

Li Hongzhang (1875), Liang Shitai. Courtesy the Loewentheil Collection

Li Hongzhang was China’s most famous statesman at the end of the 19th century, promoting the modernisation of the nation and playing a prominent role in conducting China’s relationship with the West. He was also possibly the most frequently photographed man in the country, using the new medium to circulate his image nationally and internationally and become, as the art historian Roberta Wue has written, ‘probably a more recognisable figure than any member of the Chinese imperial family’. This image reveals how Hongzhang used typical Chinese portrait conventions to craft what Wue calls ‘a sober, masculine public image’; he is depicted frontally, and formally seated beside a square table, on which the customary teacup has been placed.

Portrait of a Seated Woman (n.d.), unidentified Chinese artist. Courtesy the Loewentheil Collection

Photographs of Li Hongzhang are unusual in that the sitter was identified. Apart from photographs taken to be sold to tourists, the majority of images that have survived from the era are conventionalised portraits like this, in which both sitter and artist remain anonymous. They were most likely intended for private use, as domestic decoration.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Suzanne Treister’s tarot offers humanity a new toolbox