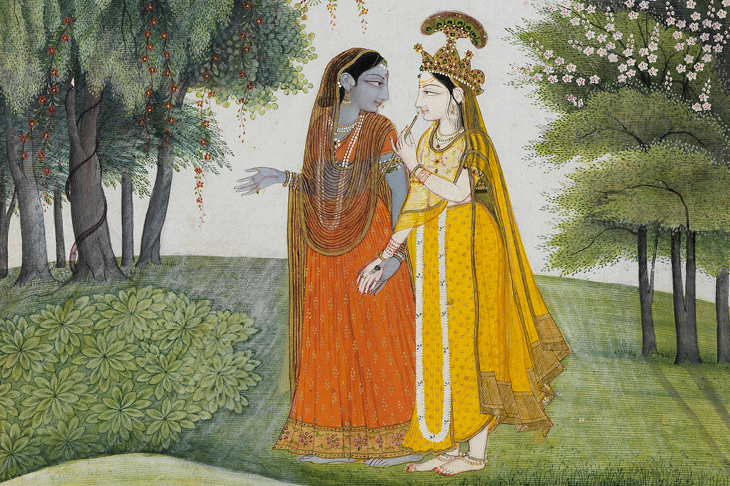

The lovers’ hands are entwined. Over the back of her hand rests his thumb; his index finger teases her fingertips. Out of sight, we imagine his middle and little finger caressing the root of her palm. She wears his lungi – he, her dupatta. He looks at her directly and she, a little coy, a little submissive, but unashamed, returns his gaze. It is a relationship not quite of equals but both are complicit. Tonight, they seem to say.

The 19th-century miniature from Kangra, a town in the Himalayan foothills of north-east India, depicts Krishna and Radha having exchanged clothes before spending the night together. Around them, nature seems to celebrate. Birds roost in lushly leafed trees and fine, almost invisible horizontal lines across foliage suggest a playful wind that toys with hems and the strands of blossom festooning the canopies. The quality of the workmanship marks it out as having been made for a member of the elite; its heart-stopping force is clearly the work of a distinct artist. Yet Kangra miniaturists seldom signed their paintings, and while efforts have been made to identify particular workshops and individuals, the artist is unknown.

It is just one of more than 30 objects on display in a new exhibition at Kettle’s Yard comprising art and artefacts whose makers’ names have been lost. Thirteen of the University of Cambridge’s museums and collections have contributed to the show, and while the reasons for objects’ makers remaining anonymous varies enormously, within their respective collections, all bear the same attribution: ‘artist unknown’.

Krishna and Radha walking by the Jumna by moonlight having exchanged clothes (detail; c. 1820), Kangra. © The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

The exhibition quietly establishes a kind of visual democracy that reflects the principles that have historically governed collections while also reflecting upon them. At the gentle end, a pair of enamelled rings from the Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences entered the collection not because of their fine floral chasing but because their original collector, naturalist Dr John Woodward (1665–1728), found their central quartzes interesting. That they weren’t decoupled from their settings is a reminder of how easily perceptions are shaped by extrinsic forces – as objects of geologic interest they also remain items of jewellery.

On a sharper note, a carved wooden head and an extravagant thumb piano from the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology throw into relief the historical treatment of ethnographic objects while simultaneously gesturing towards how those treatments are being revised. Both sculpture and instrument were brought from southern Nigeria by Northcote W. Thomas, whose habit of commissioning pieces was subject to criticism from fellow anthropologists. Whether they might have been considered artworks at the turn of the century didn’t figure – according to the discipline, commissioned objects were not genuine. Yet in the contemporary context that recognises their skill and invention, there exists no bar to the pieces being considered art. Still, their creation as works and their history as collected artefacts cannot be cleanly separated. They remain complex, complicated pieces.

Carved and painted wooden head, collected by Northcote W. Thomas in 1910, southern Nigeria. Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

Another effect of bringing together so many arbitrarily connected objects is to lend a sense of wonder to the show. It becomes a catalogue of human ingenuity and a barometer of particular circumstances. This can take quite different forms. On one wall, the lower cuff of a pair of Zoroastrian women’s trousers from Iran is stretched out flat and hung in a frame. Vertical strips of cloth in yellow, green, red and black are embroidered with chevrons and minutely detailed animals and plants – including cypress trees, which symbolise eternal life in Zoroastrianism. Their patchwork patterning tells of the Iranian sumptuary laws that forbade Zoroastrians from purchasing lengths of cloth. Equally, however, the cuff demonstrates the artistry of tailors from a persecuted minority in the face of discriminatory restrictions.

An astrolabe, a globe and a sundial in a nearby vitrine suggest a different talent for contrivance. The three intricately engraved scientific instruments purport to be from the 16th century but, like the cuff, actually date from the early 20th. They are forgeries. Quite successful ones, too – the globe, for instance, only fell under suspicion in the 1990s when the director of the Whipple Museum of the History of Science noticed that it didn’t tarnish. X-ray fluorescence analysis revealed it to be rhodium-plated, a technique invented in the 1920s. All three objects perform the functions of the originals on which they would have been based – indicating both the skill of the unknown forgers and the birth of the market for scientific instruments as collectibles. That the originals would also have been treated as decorative objects rather than put to use as scientific instruments touches the fraudulent enterprise with additional irony.

Gilt-copper astrolabe, purportedly by Johannes Bos of Rome, dated 1597, but now identified as a modern fake from c. 1920. Whipple Museum of the History of Science, University of Cambridge

Tastes and preferences are often shaped by proximate, circumstantial forces. In featuring items not often on display, ‘Artist: Unknown’ encourages visitors to reconsider institutions’ priorities while also asking themselves what they consider to be art, and why. Caught in the middle of picking fleas from its coat, a stuffed, putty-nosed monkey from the Museum of Zoology glances sideways, as if disturbed by the visitor’s presence. Yet its shop-bought eyes seem lost in thought. Should not exquisite taxidermy be considered art when it can imply the existence of a soul? In the absence of certain types of information, how much can be accurately intuited largely reflects our own partiality, or bias. Nevertheless, it’s those very biases that allow pieces like the miniature of Radha and Krishna to truly strike home.

‘Artist: Unknown, Art and Artefacts from the University of Cambridge Museums and Collections’ is at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge, until 22 September.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

What the dismantling of USAID means for world heritage