Stammtischler doesn’t have a direct translation to English. It’s a German word used to give the impression of a man who might be one of a few regulars in a pub. They’d be found at their usual table (a Stammtisch), putting the world, as they would see it, to rights.

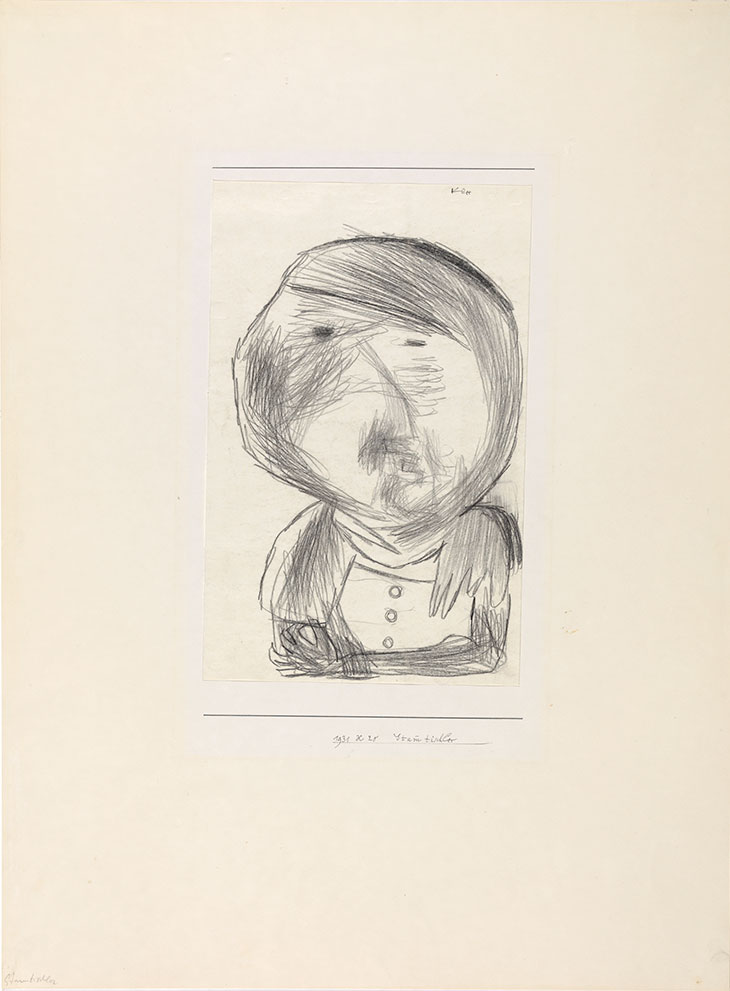

In 1931 Paul Klee titled a drawing Stammtischler, which was included in the (now temporarily closed) exhibition ‘Beyond Laughter and Tears’ at the Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern, Switzerland. It’s a messy scrawl of a drawing in black chalk, as if done by a child gripping the chalk in a tight fist. In it a man’s head balloons from a torso shown leaning on an unseen table top, as if the man sits across from the viewer. Two small dark eyes stare out from under sharp marks depicting hair plastered tightly into a side parting. Beneath a Picasso-like profile of a nose sits a smudge of black showing a small square moustache. On the invisible table top, lines curl into a claw-like hand, which appears tiny and weak beneath the comically bulbous head.

Stammtischler (1931), Paul Klee. Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern

This is Klee’s depiction of the man who would go on to become the most notorious leader in the world. Hitler’s brand of populism had, by 1931, already drawn considerable support from German people trying to deal with the consequences of the depression of the 1920s. Klee, as a university tutor and a ‘degenerate’ artist, would become one of the villains used to unite the Stammtischlers. He had taught at the Bauhaus for 10 years until 1931, when he moved to Düsseldorf to take up a professorship at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. In 1933, after his home was searched by the Gestapo and he was named as ‘a typical Galician Jew’ in a Nazi newspaper (although he wasn’t Jewish or Galician), he moved his family to Bern, where he had grown up.

Klee’s time back in Bern would turn out to be his most prolific period: in 1939 alone he recorded 1,253 new works. Completed in 2005 and housing around 40 per cent of the artist’s work in an undulating Renzo Piano-designed building, the Zentrum Paul Klee has made it part of its mission to highlight the influence Klee’s huge and broad oeuvre has had on others – witness its recent showing of ‘Lee Krasner: Living Colour’, an artist who never met Klee, and other exhibitions of Klee’s friends, recently Kandinsky and Arp.

Much of Klee’s art, similar to Stammtischler, consists of works on paper. Throughout his life Klee had produced these drawings, not as preparation for larger pieces but as works themselves. His friendship with Jacques Ernst Sonderegger, whose works are shown alongside Klee’s in ‘Beyond Laughter and Tears’, had introduced him to the idea of drawings and caricature as a valid and effective visual language for the time. Their directness allowed Klee to speak more directly to subjects, as opposed to his more nuanced abstract and Surrealist paintings.

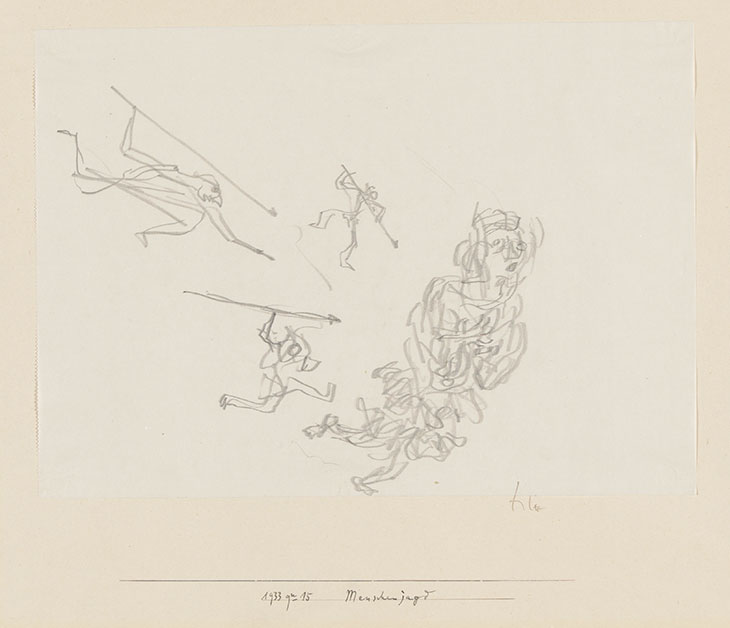

Menschenjagd (1933), Paul Klee. Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern

A work called Menschenjagd, created in 1933, has a person fleeing three smaller spear-wielding pursuers. The fleeing person is a mess of wiggly lines giving the impression of a woman in a toga fleeing a scene in a classical painting. The pursuers, however, are drawn with less intricacy; their wide strides and lack of facial expression could have been taken from a hunting scene on a cave wall. Menschenjagd translates as ‘hunting people’ or ‘man hunting’ and speaks to how Klee must have felt about those who were pushing him out of the country that had been his home for more than 30 years. The diminutive size of the chasers makes their aggression feel somewhat ridiculous: they appear like small, angry chihuahuas alongside the fleeing woman.

This ridiculous element to some of Klee’s works, and the satire found elsewhere, is likened in ‘Beyond Laughter and Tears’ to the comedy of Charlie Chaplin, someone whose films Klee wrote about watching. It’s a further example of how the Zentrum Paul Klee is setting its namesake into a broader context. Stammtischler, for instance, is hung alongside a clip from Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940), in which a Hitler-like character juggles with a globe of the Earth. Klee and Chaplin both sought to combat Hitler and his ideology through satire – Chaplin by portraying him as a childlike fantasist and Klee as a sad drunk in a pub.

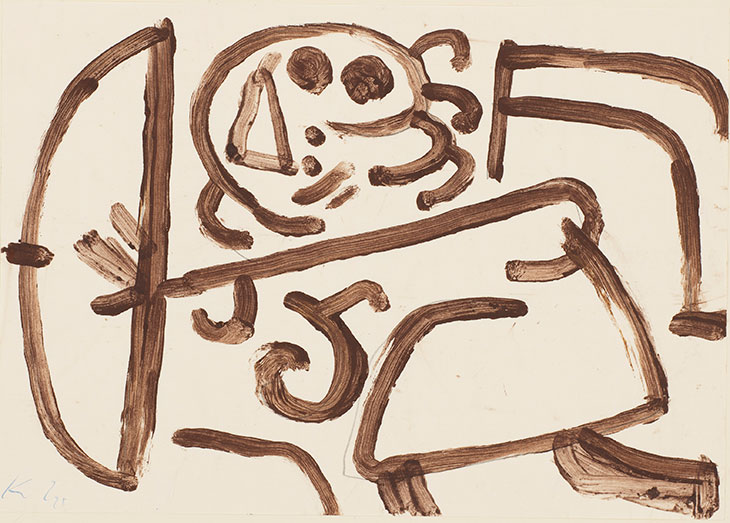

Regen=und Sturmangriff (‘Rain and Storm Attack’) (1939; detail), Paul Klee. Photo: Kerry McFate; Courtesy David Zwirner; © Klee Family

Humour in Klee’s drawings continued until the end of his life. David Zwirner’s (temporarily closed) London exhibition of ‘Late Klee’ focuses on his time of great productivity in Bern. (Zwirner has represented Klee’s family since April 2019, whose holdings are regularly loaned to both the Zentrum Paul Klee and David Zwirner Gallery.) After a five-year struggle with an unknown illness (now thought to have been scleroderma), Klee died in 1940. Regen=und Sturmangriff (‘Rain and Storm Attack’), made the year before, is composed of thick brown lines of paint swirling around the paper, whipping up a scene that wouldn’t feel out of place in a Chaplin film: a person pitched comically, umbrella first, against a storm.

The Zentrum Paul Klee is temporarily closed to the public due to the Covid-19 outbreak. For more information on ‘Beyond Laughter and Tears: Klee, Chaplin, Sonderegger’ (scheduled to run until 24 May) visit the institution’s website. David Zwirner, London is closed for the same reason. For more information on ‘Late Klee’, visit the gallery’s website.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘He wasn’t edgy. He was honest’ – on the genius of David Lynch