The opening of the Postal Museum in London last July marked a significant moment in the history of the British postal system. The Post Office traces its origins to 1516, when Henry VIII appointed his secretary Brian Tuke as Governor of the King’s Posts. It was, so to speak, a soft launch (not least because Tuke had been running Henry’s diplomatic correspondence for several years already) and it would be another century before the general public was permitted to consign its own correspondence to the royal mailbags. One constant feature, however – ever since Tuke commissioned his own portrait from Hans Holbein in the 1520s – has been the association between the postal system and the artists for whom it has played the various roles of subject, patron, gallerist, and employer.

By the end of the 17th century, the ‘General Post Office’, as it had become after the Restoration, was firmly established in headquarters in the City of London, where a small army of red-frock-coated clerks undertook to sort and dispatch the nation’s correspondence. The scene is nicely captured in Thomas Rowlandson and Augustus Charles Pugin’s illustration of the Lombard Street Sorting Office, made for Rudolph Ackermann’s collection of colour plates in The Microcosm of London (1808–10). But the mail carried more than letters. These were the years of Aboukir Bay and Trafalgar, and Rowlandson and Pugin’s clerks call to mind those other armies of red-coated Britons, news of whose victories and defeats would travel through such rooms on the way to the corners of the nation. At the height of the Napoleonic Wars, according to Thomas De Quincey, it was the carriages of the Post Office ‘that distributed over the face of the land, like the opening of apocalyptic vials, the heartshaking news of Trafalgar, of Salamanca, of Vittoria, of Waterloo’. In The English Mail-Coach (1849), De Quincey describes the chaotic scene outside the Lombard Street office, where drivers and passengers gathered to convey correspondence – and national sentiment – to the provinces, where ‘horses, men, carriages – all are dressed in laurels and flowers, oak-leaves and ribbons’.

The Post Office (1809), Thomas Rowlandson after Augustus Charles Pugin. Yale Center for British Art, New Haven

Decked out in the pomp of victory, stamped with the livery of the king, the mail-coach came to emblematise the nation itself in images like Stage Coach With the News of Peace (1815) by James Pollard, who made rather a speciality of coaching scenes. The bustling urban spectacle of the mail is nicely illustrated in Pollard’s North Country Mails at the Peacock, Islington (1821), and a print of his depiction of the Winterslow Lioness incident of 1817 – when an escapee from a travelling menagerie had savaged the lead horse of the Exeter Mail – is a star attraction in the Postal Museum’s permanent exhibition.

Stage Coach with the News of Peace (1815), Robert Havell after James Pollard. Yale Center for British Art, New Haven

To De Quincey, the mail was more than just an image of nationhood or a spectacle in its own right. Mounted on the box, the attentive passenger underwent a new kind of training in aesthetics. Like his beloved opium, the mail-coach introduced the young De Quincey to previously unimaginable visions, not only the ‘glory of motion’ engendered by its sheer velocity, but subtler effects, too: the ‘animal beauty and power’ of the coach-horses, and the way the eye of the wakeful mail-rider would glance ‘between lamplight and the darkness upon solitary roads’. Unlike the railways, which by the 1840s had begun to supersede it, the mail-coach was Romantic in the proper sense, tinged with the sublime, an image of reason’s precarious survival ‘in the midst of vast distances – of storms, of darkness, of danger’. The dashing modernity captured in images like George Robertson’s The Mail Coach (c. 1786) – in which a streamlined official vehicle tears past the skittish horses assembled outside a tumbledown country inn – had by the 1830s been replaced by the garish, self-conscious Romanticism of Charles Cooper Henderson’s Mail Coach in a Snowstorm (c. 1835–40) or any number of nostalgic scenes by the genre painter Henry Alken. De Quincey’s mail-coach was fast disappearing into the mists of memory.

The Post Office itself, meanwhile, was about to undergo the greatest expansion in its history as a result of the reforms proposed by the campaigner Rowland Hill, the most significant of which was the introduction of the Uniform Penny Post in January 1840. At a penny per letter, postal communication came within the reach of most literate citizens while giving others a definite reason to strive for literacy, and the resulting explosion in the volume of correspondence very nearly overwhelmed the capabilities of the service. For a contemporary account of the 19th-century’s famed information explosion one need look no further than Hill’s diary entry on the day after the introduction of the penny post: ‘January 11th.—The number of letters despatched last night exceeded all expectation […] Great confusion in the hall of the Post Office, owing to the insufficiency of means for receiving the postage.’ The General Post Office – relocated from Lombard Street to Robert Smirke’s grand neoclassical building at St Martins-le-Grand in 1829 – soon became a hub of activity for all classes of people, who gathered not, as in De Quincey’s youth, to watch the departure of the evening coaches, but to catch the day’s last collection.

If the Georgian mail-coach had helped to unify the nation, disseminating the image of sovereignty along with letters and news, the Victorian crowd assembled in George Elgar Hicks’s The General Post Office, One Minute to Six (1860) might be thought to display a very different kind of postal scene. Intent on their own private purposes, Hicks’s diverse and jostling citizenry scatters packages this way and that, jockeying for position, an assortment of self-interested persons rather than a community united in fellow-feeling. And yet it is precisely the system of the mail itself – in the rhythm of communication ordained by its schedule – that brings together, though unconsciously, this ragtag bunch of individuals, each lost in contemplation of his or her own aim. The movement of the painting, the current of its attention, flows this way and that; yet taken as a whole the energy of the crowd – duly directed by the post-master’s pointing finger – carries it, and the gaze of the viewer, from left to right, to the mailboxes or receiving clerks who must be waiting beyond the frame to receive the items borne by each supplicant. What unites these people is the shared medium through which they are about to reach out across distance to other individuals, in other, unseen locations. Come six o’clock, when the office closes and the crowd is obliged to disperse, each taking their solitary way, the heterogeneous mass of their letters and packages will remain here to be collected, sorted, packed and carried, before emerging elsewhere, each missive’s unique character magically restored.

The General Post Office, One Minute to Six (1860), George Elgar Hicks. Museum of London

This compelling story of how we are brought together through the mail not only with our intended correspondents but also, inadvertently, with the untold masses of others whose letters and packages sit cheek-by-jowl with our own in the intimate spaces of mailbag and sorting-tray, may be one reason that the Post Office occupies such an important place not only in the public iconography of British nationhood, but also in the private spaces of the British imagination. It is surely no coincidence that the golden age of British postal art coincided with the febrile political climate of the years between the world wars, when the relationship between the individual and the mass became the crucial political question both for the fascist right, whose supporters had been emboldened by the rise of Mussolini and Hitler, and for the communist left, whose world view (though not, in most cases, its practical aims or methods) had found favour among British artists and intellectuals.

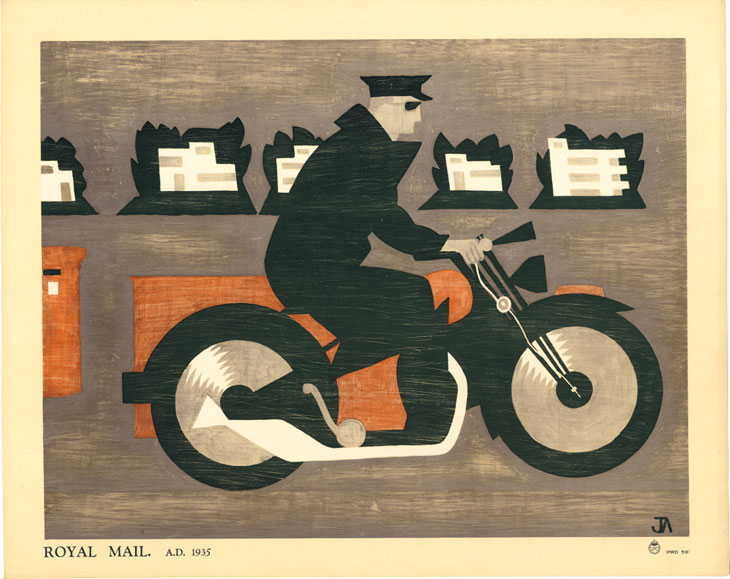

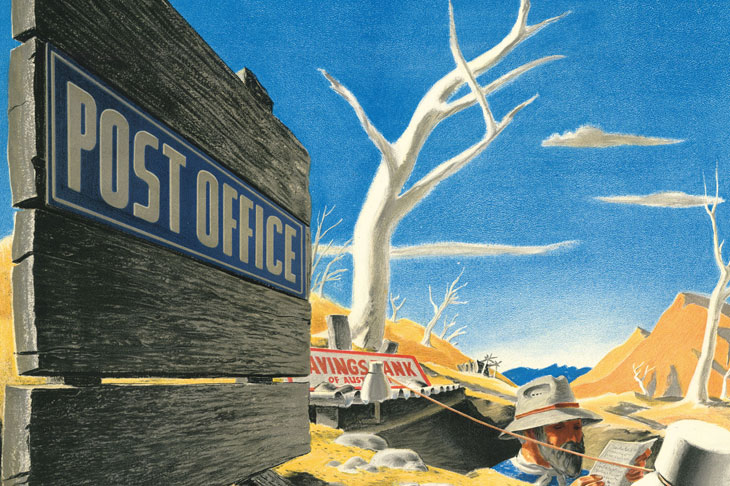

Throughout the 1930s the GPO hired modernist painters and illustrators like Duncan Grant, John Armstrong, E. McKnight Kauffer, and John Vickery to burnish the image of the Post Office, to inform the public about changes, and to publicise new services such as the expansion of airmail routes throughout the empire. But there was more at stake than mere publicity. Like the documentary films produced by the GPO’s film unit in this decade under the pioneering producer John Grierson, these artworks were designed not only to convey information, but to bind together disparate territories and communities within Britain and beyond in a shared history, a shared sense of identity and purpose, and a shared image of the liberal, inclusive modern society. The series of prints commissioned by the GPO from Armstrong in 1935, for instance, consists of four gouache illustrations of scenes from the history of human communication, ranging from a red-figure style depiction of the Athenian courier Pheidippides through a medieval messenger and a Georgian mail-coach to a 1930s postman mounted on a motorcycle. Where Armstrong’s sequence stresses the historical continuity of communication, in which the contemporary post office not only carries packages and letters but also transmits tradition, others emphasised spatial continuity. Kauffer’s Outposts of Britain series (1937) depicts the work of urban and rural postmen from Land’s End to the Scottish highlands, while Vickery’s Outposts of Empire, created for the same line of educational posters, works to establish a circuit of postal exchange connecting the heart of the empire with the colonial zones understood as its distant periphery. Local postmen in Ceylon, Southern Rhodesia, and Barbados carry mailbags on foot, by bicycle, and by horse-and-cart respectively. Meanwhile, Vickery’s Australian postman – whose outback dugout does double duty as a branch of the Savings Bank of Australia – reads a letter behind the taut wire of the telegraph or telephone disappearing out of frame, a symbol of the network of technology and capital through which this exemplary imperial pioneer is integrated into a global community of British subjects.

Royal Mail A.D. 1935 (1935), John Armstrong. Royal Mail Archive, Postal Museum Royal Mail Group, courtesy the Postal Museum

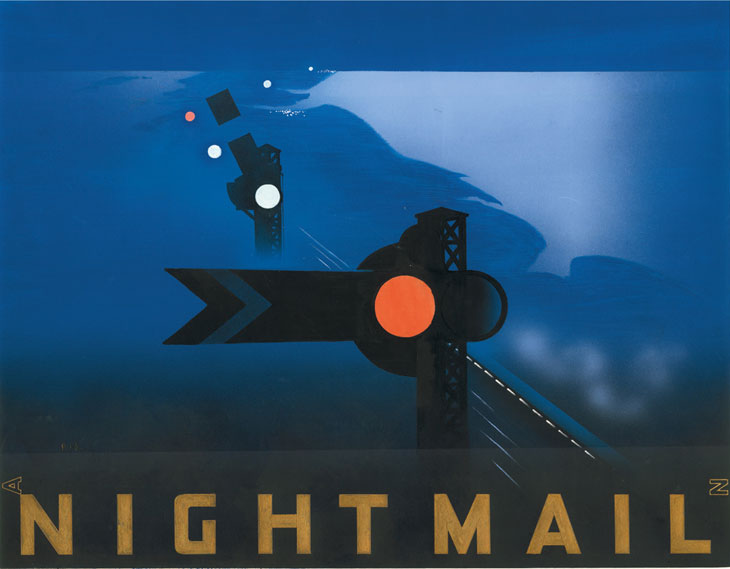

These images can be understood as portraying an updated, global version of the same scene depicted by Hicks, in which the Post Office contributes to the production of a social world by mediating indirectly between the private individual and the mass of society. The obligation to tell that story, in as many media as possible, was one that the GPO of the 1930s took very seriously indeed. Perhaps the most celebrated GPO work of these years – perhaps the most famous of all artefacts of British postal culture – is Basil Wright and Harry Watt’s film Night Mail (1936). Publicised with the help of an atmospheric poster by Pat Keely, the film follows the outbound mail north from London to Scotland, borne through the night to the sound of verses specially composed by W.H. Auden:

This is the night mail crossing the Border,

Bringing the cheque and the postal order,

Letters for the rich, letters for the poor,

The shop at the corner, the girl next door.

In common with much of the GPO’s public art in the 1930s, Auden’s poem, together with the film it accompanies, celebrates not only the unity of purpose and technical achievement represented by the postal system, but also – and no less importantly – the diversity of those who ‘wake […] and long for letters’, whose innate sociability and desire for communication make the service both necessary and possible.

Poster for Night Mail (1936), designed by Pat Keely. Royal Mail Archive, Postal Museum, London. Royal Mail Group, courtesy the Postal Museum

This consistent message of unity in diversity remained the central pillar of the GPO’s contribution to public morale after the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939. While Grierson’s documentarists went into khaki as the Crown Film Unit, Kauffer and other GPO artists provided publicity materials to the Ministry of Information and other wartime departments. The GPO kept letters moving even at the height of the Blitz, despite repeated targeting of postal depots, telephone exchanges, and other parts of the national communication system. Struck on 18 June 1943 by incendiary bombs in an attack that killed two, the gutted frame of the main sorting office at Mount Pleasant – where the Postal Museum now stands – is captured in L. Francis Nichols’s Smouldering Mail Bags at Mount Pleasant (1943), in which the heaped sacks, twisted rafters, and perspective may be designed to recall John Lavery’s famous First World War depiction of the Army Post Office 3 at Boulogne (1919).

After the war, the GPO briefly saw a late flowering of design as artists returned from wartime service with government ministries, but the postal aesthetic never regained the dynamism and excitement of its interwar modernist heyday. When the willingness to experiment finally did return, it came in a somewhat unlikely form. Since the introduction of the Penny Black in 1840, plain stamps had been issued with the image of the monarch in profile or three-quarter view. From 1924, occasional pictorial ‘commemoratives’ began to appear, marking events of national significance like that summer’s British Empire Exhibition. By the late 1950s, the Post Office had begun tentatively to relax its rules on stamp design, and commemoratives began to be issued with increasing frequency. This new visual liberality received a boost under the oversight of Tony Benn, who became Postmaster General in 1964. Benn’s contribution to the history of the Post Office is in itself worth noting: not only did he oversee the completion of the GPO Tower in Fitzrovia, a lasting symbol of the Post Office and of the London of the 1960s, but he also helped to set up the National Postal Museum, a forerunner of the new institution.

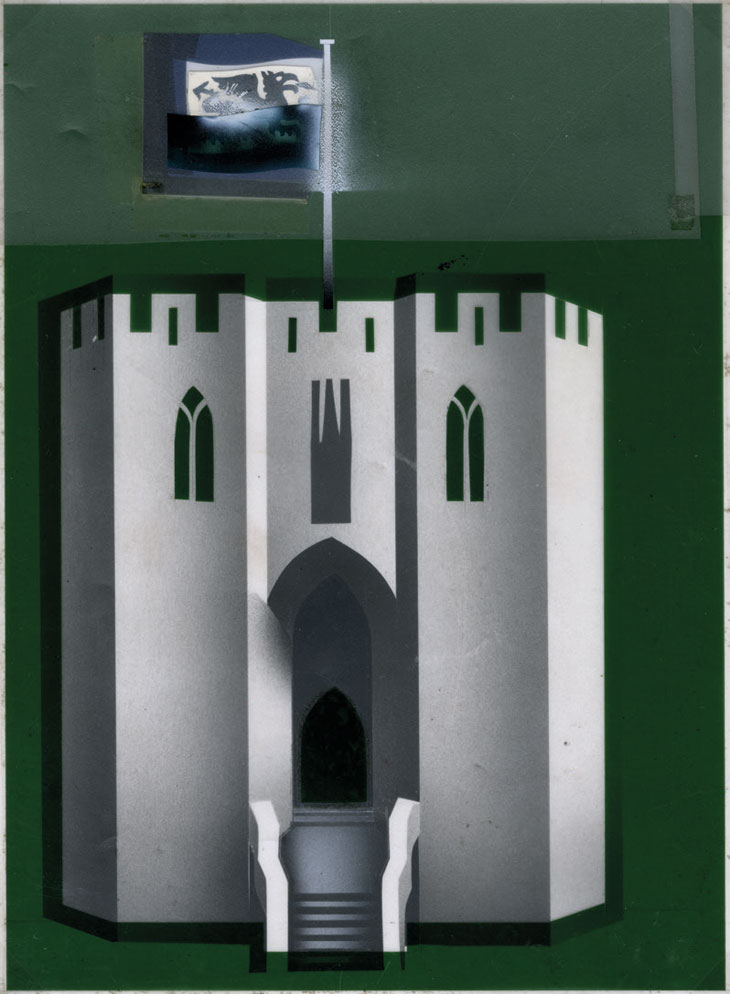

It was a chance letter from the artist David Gentleman, in response to Benn’s announcement of a public consultation on stamp policy, that was to lead to the Post Office’s farthest-reaching and longest-running programme of public art. Gentleman had already been responsible for a number of commemorative stamps issued by the GPO, but felt constrained as a designer by the requirement that the queen’s head should be included in its full form on all stamps issued. Together, Gentleman and Benn laid plans for reform. Their radical, even republican, proposal – that the queen might disappear from British stamps altogether – was never likely to pass muster at Buckingham Palace. But they did reach a compromise: from now on, artists proposing stamp designs would be permitted a relatively unobtrusive silhouette of the monarch’s profile in the corner of the image. Thus freed from one of the main impediments to innovation, Gentleman, along with other designers including Ann and David Gillespie, Andrew Restall, Reginald Lander, and Jerzy Karo, produced countless striking and inventive designs which, once approved for use, brought minuscule works of GPO modernism to the recipients of letters and parcels across the nation.

Preliminary drawing by David Gentleman of the King’s Gate at Caernarvon Castle, for use on stamps to honour the investiture of the Prince of Wales in 1969. Royal Mail Archive, Postal Museum, London. Royal Mail Group, courtesy the Postal Museum

Gentleman, more than anyone else, was responsible for demonstrating the possibilities of the postage stamp, a tiny shard of visual pleasure and interest that could make art a natural accompaniment to the everyday act of communication for millions of people. But the most compelling use of the stamp as a medium for contemporary art seems destined never to enter into circulation at all. Commissioned as an official war artist by the Imperial War Museum in 2003, Steve McQueen produced a set of 136 sheets of commemorative stamps, each bearing the face of a British soldier killed in Iraq since 2003 and multiply reproduced on a 12 x 14 sheet (168 stamps per sheet). Despite a campaign supported by the families of the dead, as well as the request of the artist himself, Royal Mail has so far declined to issue McQueen’s designs; the sheets, along with the wooden casket in which they are displayed, were acquired by the IWM in 2007.

When I visited the Postal Museum shortly after its opening last summer, there was no mention in the exhibition gallery of McQueen’s work, nor any recognition of those moments in the history of the Post Office that might unsettle the narrative of national unity. There was no mention, for instance, of the satirical letter-seals produced and distributed by Punch in protest at government postal surveillance in the 1840s, nor any reproduction of Walter Paget’s Birth of the Irish Republic (1916), depicting the interior of the occupied Dublin Post Office during the Easter Rising. No doubt the Winterslow Lioness, complete with dubious sound-effects, is a more family-friendly exhibit. But given the Post Office’s previous success in projecting through art a national image that depends on diversity and dissent as well as on unity, it perhaps isn’t absurd to hope that the museum, as it carries on the tradition of postal art, might find ways to tell a wider and bolder set of stories, too.

From the January issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Seeing London through Frank Auerbach’s eyes