Two large, glooping, monochrome figures survey us as they waddle on tiny feet through a landscape of webbed, heat-cracked black. Their features are white-on-white, channels of shadow scored with the brush-end into the thick paint. One smiles crookedly beneath a generous swash of nose; the other is more severe, his thin, straight nose driving squinting, interrogative eyes to the top of his head. These are Life and Hope. They look like the bedsheet ghosts we imagine as children. Or perhaps a haunted salt-and-pepper set out for a night-time stroll. Beside them, scratched into the black, an upside-down angel hovers, or rather dangles: a puckish self-portrait of the artist, Franciszka Themerson (1907–88). The painting’s title, a line from Apollinaire, is Comme la vie est lente et comme l’espérance est violente (1959) (‘How slow life is and how violent hope’), and the defusing of the line’s anguish – the rendering of Life and Hope as globular and cartoonish – is pure Themerson. The painting was acquired by Tate Britain earlier this year and is now the centrepiece of a small exhibition that highlights the variety of Themerson’s work.

How slow life is and how violent hope (1959), Franciszka Themerson. Tate, London. Photo: Tate/Oliver Cowling; © Estate of Franciszka Themerson and Stefan Themerson

Themerson was born in Poland in 1907, the daughter of the Jewish artist Jakub Weinles. She trained for seven years at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts but graduated in 1931 feeling frustrated by its conventionality. It was during this time, however, that she met and married Stefan Themerson, an architecture student three years her junior, with whom she would spend the rest of her life.

In the 1930s, the Themersons began using borrowed equipment to make films together, some of the earliest works of Polish experimental cinema. On show at the Tate is Europa (1931), their bleak anti-fascist masterpiece, thought to have been destroyed by the Nazis until a print of it was discovered in a German archive in 2019. Beside this, and rather different in tone, is The Adventure of a Good Citizen (1937), an ‘irrational humoresque’ about a man who decides – to the fury of his compatriots – to see what happens if he walks backwards instead of forwards.

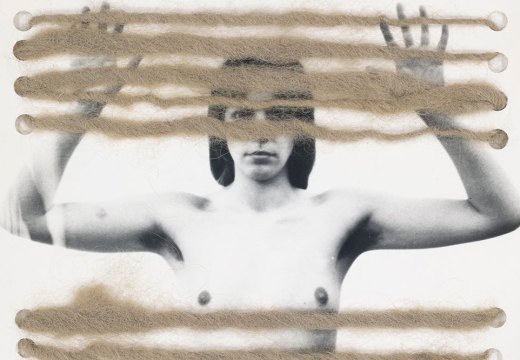

Still from The Adventure of a Good Citizen, 1937, directed by Franciszka Themerson and Stefan Themerson. Tate, London. © Estate of Franciszka Themerson and Stefan Themerson

In 1938, with five films under their belt and wanting to be nearer the action, the couple moved to Paris, only for war to break out and the city to fall to the Nazis. While Stefan enlisted in the chaotic Polish infantry division that was formed and almost immediately disbanded in France, Franciszka escaped to London, where she worked for the Polish government-in-exile while trying to arrange passage for her husband to join her in England.

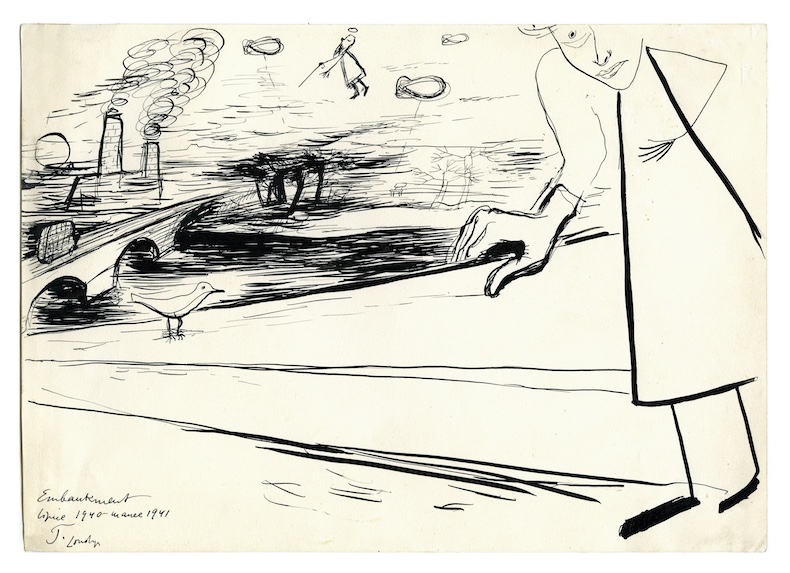

Much of the Tate’s exhibition is given over to Themerson’s ink drawings from this period, depictions of loneliness and everyday fear in wartime London. These are part of the Unposted Letters series, her one-sided correspondence with Stefan while he was uncontactable, either in hiding or in a Red Cross camp in Vichy France. Some of the drawings are straightforward: air raid sirens, or huddled sleepers on the platform at King’s Cross; in others, however, those avant-garde influences start to make themselves felt again through dive-bombed Madonnas and red suns among the barrage balloons. ‘Crawling out of me is some surrealist from under a black star,’ Themerson wrote. ‘Perhaps I will manage to control it.’

Embankment (Self portrait) (1940–41), Franciszka Themerson. © Estate of Franciszka Themerson and Stefan Themerson

In the midst of all this, Themerson developed another more surprising interest. In a letter to Stefan from 1940, she described encountering the drawings of Edward Lear for the first time: ‘I felt electrified, like someone who can suddenly feel the ground alive under her feet again.’ One can see Lear’s influence in some of the later Unposted Letters – for example, in the roller-skated secretary dashing between her tortured, self-important bosses, in the way that comedy is often only a translucent layer placed over the desperation of the characters, or that lightness and sadness can be brought delicately together.

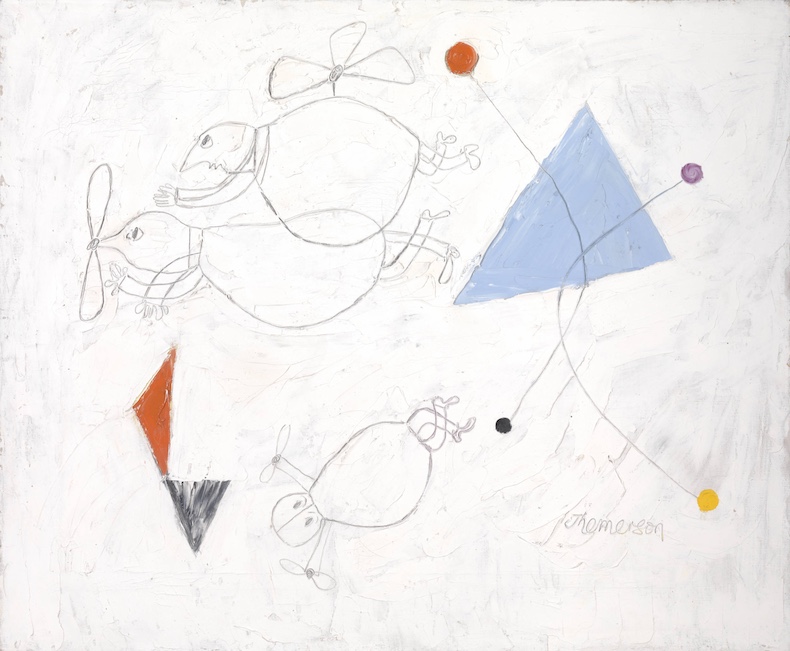

After the war, Themerson returned to painting, and the three large canvases that round off the exhibition, all from the 1950s, are its most satisfying components. Alongside the figures of Life and Hope hangs Two Pious Persons Making their Way to Heaven, one propellered, one helicoptered, with a little angel below (1951), a painting – part Malevich, part Lear – in which two figures, portly and pompous, doodle-scratched into the white paint, pass by geometric blocks of colour on their heavenly ascent.

It is a shame that the exhibition doesn’t find space for the work for which Themerson is best known: her illustrations and book designs for the Gaberbocchus Press. This was the publishing house that she and Stefan founded and ran for three decades from their home in west London, specialising in introducing the works of the European avant-garde to English readers. When Gaberbocchus published the first English translation of Alfred Jarry’s play Ubu Roi in 1951, Franciszka’s celebrated illustrations led to a sideline in set design, as well as a spin-off comic book. In Ubu, Themerson had found her ideal subject: the dictator whose cruelty and grotesqueness could be unpicked – neutralised, even – by making him soft and ridiculous.

Two Pious Persons Making their Way to Heaven, one propellered, one helicoptered, with a little angel below (1951), Franciszka Themerson. Tate, London. Courtesy Tate; © Estate of Franciszka Themerson and Stefan Themerson

‘Franciszka Themerson: Walking Backwards’ is at Tate Britain, London, until 30 March 2025.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Pilgrims’ progress? The Vatican Jubilee has frustrated Romans and tourists alike