From the May 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Towards the end of his life, Kafka was shrinking. He first spat blood in 1917, and by 1924 he was lying in a sanatorium, unable to swallow properly because of tuberculosis of the larynx, and gradually becoming thinner and thinner as a result. In some ways it was a fitting end for a writer who had often thought of his flesh as something he needed to escape. He had sad fantasies of being sliced up like roast meat, or of being a log and having shavings drawn off him, or of lying down on a railway track to have his head and legs amputated by a passing train. Even his own insides appeared to be ready to shrink back from the parts of him that other people could see and touch. ‘I feel so loose inside my skin,’ he once complained, that ‘it would only have needed someone to give it a shake for me to lose myself completely.’

Towards the end of his life, Kafka was shrinking. He first spat blood in 1917, and by 1924 he was lying in a sanatorium, unable to swallow properly because of tuberculosis of the larynx, and gradually becoming thinner and thinner as a result. In some ways it was a fitting end for a writer who had often thought of his flesh as something he needed to escape. He had sad fantasies of being sliced up like roast meat, or of being a log and having shavings drawn off him, or of lying down on a railway track to have his head and legs amputated by a passing train. Even his own insides appeared to be ready to shrink back from the parts of him that other people could see and touch. ‘I feel so loose inside my skin,’ he once complained, that ‘it would only have needed someone to give it a shake for me to lose myself completely.’

Some of his most popular stories attempted to give these ideas a narrative shape. The last work he revised was ‘A Hunger Artist’, about a man who starves himself to death; the last he wrote was about a singing mouse called Josephine, in which Kafka wondered, ‘Is it her singing that charms us or isn’t it rather the solemn stillness that surrounds the feeble little voice?’ He might have been describing himself. Ashamed of taking up so much space even on paper, and exhausted by what he called ‘the impossibility of writing, the impossibility of not writing’, he had abandoned many earlier stories unfinished, seemingly unwilling or unable to fulfil their potential. Repeatedly, he treated his sentences like the sensitive feelers of an insect, reaching out enquiringly into the world, before shrinking back in horror at the prospect of being fingered by the strange hands of his readers.

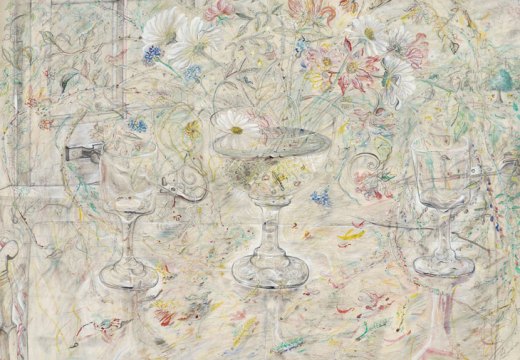

There is a similar imaginative pattern in his surviving drawings, now assembled and published together for the first time in a sumptuous volume edited by Andreas Kilcher, with a catalogue raisonné by Pavel Schmidt. Many of these drawings feature human bodies that have been reduced to a handful of lines sketched in pen or pencil. Ghostly heads hover in mid-air, like distant relatives of Lewis Carroll’s Cheshire Cat. A few figures cluster in groups – anonymous crowds and faceless soldiers on parade – while Kafka was also attracted to images such as an acrobat wobbling on a tall ladder supported by another acrobat’s feet: a memory of some Japanese equilibrists he had seen at Prague’s Théâtre Variété in 1909, and a powerful visual metaphor for his own wariness at having to depend on other people. Perhaps that is why most of the other figures in his drawings are alone: fencers thrusting at invisible opponents, or dancers caught mid twirl, or, perhaps most tellingly, someone sitting at an empty desk with their legs splayed and their head in their hands: a caricature of the writer at work, and perhaps the closest Kafka ever came to a truly candid self-portrait.

Figure cut out of sketchbook (c. 1901–07), Franz Kafka. Courtesy National Library of Israel, Jerusalem

The survival of these drawings can be attributed to Kafka’s friend and literary executor Max Brod, who chose to ignore the writer’s last wish that any unpublished manuscripts ‘or drawings that you have’ should be burned. However, it turns out that Brod was also indirectly responsible for the fact that only now is it possible to see the full range of what he once described as Kafka’s ‘double talent’ at work and at play. At some point, Brod chose to bequeath these notebooks and diaries to his former secretary Ilse Esther Hoffe, who grimly clung on to them until her death in 2007 at the age of 101. It was not until the Supreme Court of Israel ruled in 2016 that Brod’s papers should be entrusted to the National Library in Jerusalem, a decision accepted three years later in Switzerland, where the papers were being stored in a bank vault, that they became accessible to the wider public for the first time.

Were they worth preserving? According to this volume’s contributors, the answer is an unequivocal yes. Kilcher argues that the drawings represent ‘the last great unknown trove of Kafka’s works’, and in a long and detailed historical essay he outlines Kafka’s fascination with visual art – the university lectures he attended, the pictures he bought, the exhibitions he attended – and its influence on his writing. (He is especially persuasive on the deep impression made on Kafka by the stripped back aesthetic of Japanese drawing and printing techniques.) In a second essay, Judith Butler offers a beautifully intricate meditation on Kafka’s desire to sketch fantastical bodies that are suspended in mid-air, as if untethered from gravity, leaving behind a world in which real bodies need food or shelter or other people to survive. ‘Becoming line is becoming lean,’ Butler observes, ‘but also becoming impossibly light, leaving the ground.’

Such lyrical flights won’t convince everyone that Kafka was a serious artist, any more than earlier comparisons with Paul Klee or Alberto Giacometti had persuaded many readers that his drawings were anywhere near as important as his writings. Some of them – a few squiggly lines found on a piece of scrap paper, some elaborate cross-hatching on a postcard – barely qualify as drawings at all. Describing such productions as ‘imageless images’, as Kilcher does, sounds like a slightly hopeful attempt to add some intellectual heft to what seem far more likely to be distracted doodles rather than masterpieces of minimalism. But still, as windows into Kafka’s elusive, elliptical imagination they are fascinating. To borrow the writer’s own description of his short-story collection Contemplation (1912), they show his commitment to ‘sticking finger-tips into the truth’ and sharing what he found there.

Franz Kafka: The Drawings, edited by Andreas Kilcher with Pavel Schmidt and Judith Butler and translated by Kurt Beals is published by Yale University Press.

From the May 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

When the Nazis pilloried modern art