From the April 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In her ‘Thoughts on Autobiography from an Abandoned Autobiography’, a short essay she wrote for the New York Review of Books in 2010, Janet Malcolm observed that she became a journalist ‘precisely because she didn’t want to find herself alone in the room’. It is, for profile writers like Malcolm, easy enough to create an ‘I’ that can ask questions, that can be the driver of the plots of other people’s lives; harder to become a subject herself. Forty years of performative anonymity, of encouraging others to talk for her involved and involving portraits of lives in the New Yorker, had, she said, left their mark: ‘I see that my journalist’s habits have inhibited my self-love. Not only have I failed to make my young self as interesting as the strangers I have written about, but I have withheld my affection.’

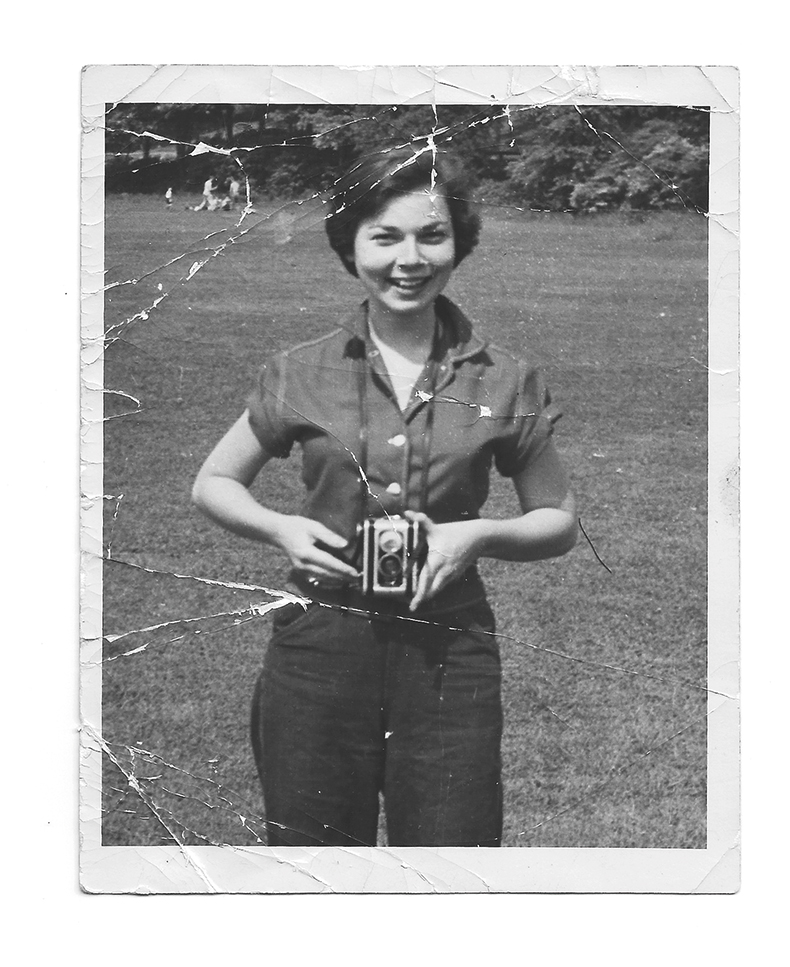

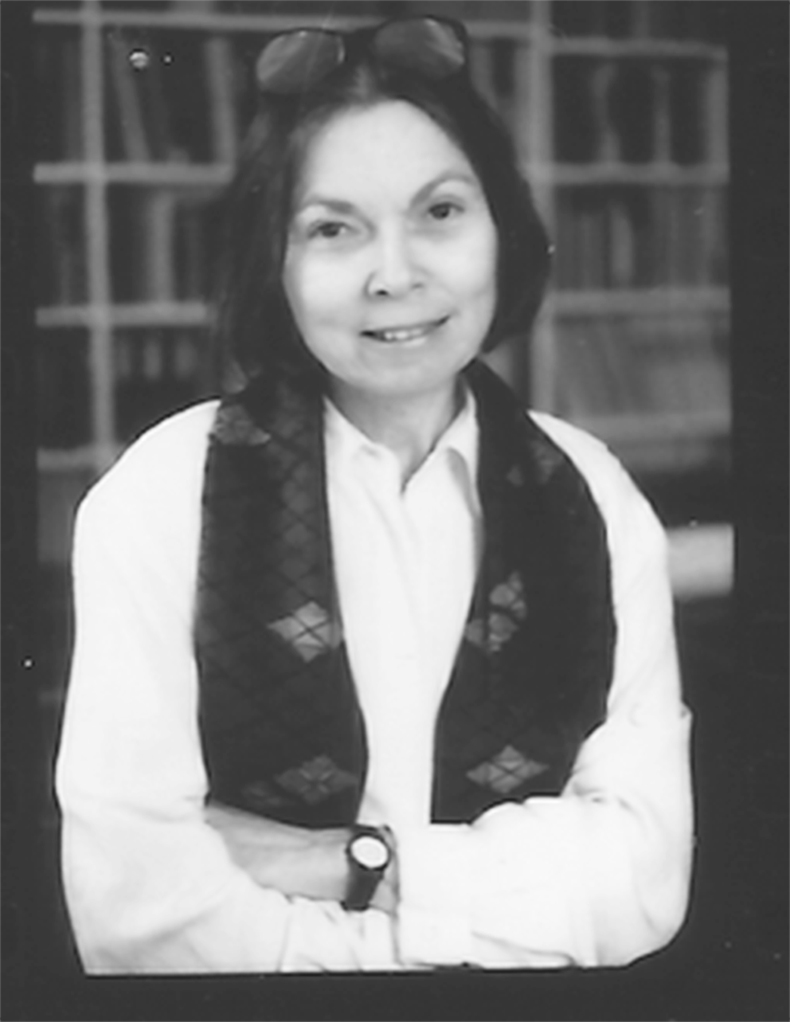

In the last chapter of her life, before she died of lung cancer, at the age of 86, in 2021, Malcolm did, however, try to give a little writerly love to her own past. In order to access that lost time, she turned to boxes of family photographs, snatched and blurred instants from the flow of memory, and examined them with the cool photography critic’s eye with which she first made her name. This book, a collection of brief essays that meditate on those images, the truths they hint at and the lies they tell, is the result of that attention. In her afterword, Anne Malcolm, the author’s daughter, notes that her mother might in another life have become a professional photographer – in among her papers Anne found a never-used typewritten price list for a planned portrait studio. Instead, Malcolm developed a kind of dark-room magic with words on a page. No one was more alive to the ethical questions of putting anything down on paper at all – there is an almost scientific care to these pieces. The author of The Journalist and the Murderer (1990), who could famously write that ‘Every journalist who is not too stupid or full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible’ was not about to indulge any anecdotal licence where her own past was concerned.

In the last chapter of her life, before she died of lung cancer, at the age of 86, in 2021, Malcolm did, however, try to give a little writerly love to her own past. In order to access that lost time, she turned to boxes of family photographs, snatched and blurred instants from the flow of memory, and examined them with the cool photography critic’s eye with which she first made her name. This book, a collection of brief essays that meditate on those images, the truths they hint at and the lies they tell, is the result of that attention. In her afterword, Anne Malcolm, the author’s daughter, notes that her mother might in another life have become a professional photographer – in among her papers Anne found a never-used typewritten price list for a planned portrait studio. Instead, Malcolm developed a kind of dark-room magic with words on a page. No one was more alive to the ethical questions of putting anything down on paper at all – there is an almost scientific care to these pieces. The author of The Journalist and the Murderer (1990), who could famously write that ‘Every journalist who is not too stupid or full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible’ was not about to indulge any anecdotal licence where her own past was concerned.

The result is a wary almost-memoir, as much about the lacunae of memory as about memories themselves. Perhaps that wariness is rooted in the precarious luck of her life. Her book begins in escape from far too much reality: the second picture here sees her as ‘the girl on the train’, five years old and between her mother and father, leaning out of a carriage window, en route from Nazi-occupied Prague in July 1939. The family story had it that her Jewish father, a doctor, had bribed an SS officer for visas allowing passage to America with the gift of a racehorse.

The personal consequence of that uprooted past is the theme that Malcolm nags at here. Who were those aunts and uncles and family friends from back home who found themselves spared and adrift, staring into Kodak Brownie camera lenses in New York in the 1940s? What particular Czech-ness did they imbue her with? She senses both a Bohemian quickness of wit, and a familial desire never to be tainted by other caricatures, of being ‘boorish and ham-fisted’. She sifts through what family letters remain to try to catch the tone of those years – the forgotten car trips in which she told dirty jokes to her cousin, say – and examines how honestly she can reinhabit them: ‘The past is a country that issues no visas. We can only enter it illegally.’

Courtesy Granta Books; © Anne Malcolm

Somewhere near the heart of all these stories is Malcolm’s father, with his ‘preposterous ambitions for his daughters [and] the bestsellers he expected us to write’. He is pictured grinning broadly in middle age, with the wicker basket he took on country walks to collect wild flowers. The short essay she devotes to him alone is the simplest expression of love here; a catalogue of his own loves – ‘opera, birds, mushrooms, poetry, baseball’ – and the singular space he occupied in her mind. His death gave her the understanding that seems to inflect her thinking about her own mortality, the knowledge that haunts all family albums: ‘When we die our species dies with us. Nobody like us will ever exist again.’

As the book advances, Malcolm’s memory finds fewer pictures on which it wants to snag. The story of her second marriage, to New Yorker editor Gardner Botsford, is told in two fleeting images. The first is a thought of a specific piece of Italian china with a ‘faux-folk art flower design’ which she had bought for an apartment she and Botsford rented when they were conducting a secret adulterous affair; the second is a snapshot of an unknown couple on a tennis court, which Botsford prized for its hopeless composition (and which Malcolm subsequently delighted in smuggling into a published introduction to the street-art pictures of Garry Winogrand and William Eggleston). That those two stories are all that remains, or all that she cared to share, of the lasting love of her life is characteristic. It is a measure of her understanding of detail that you might build from them an entire portrait of a marriage.

Courtesy Granta Books; © Anne Malcolm

Malcolm wonders at this habit of discrimination in herself. She traces it in her first identifiable memory. She wants to join in a procession of nursery school girls, strewing rose petals from baskets, but she has no basket of petals. Her aunt gives her some white peony petals from a nearby bush but, she recalls, ‘I feel cheated that I have not been given the real thing, but something counterfeit.’ Malcolm is inclined to believe she never forgot that feeling, that her memory gave it status because it informed her sensibility from that day on. But then, of course, as this book also knows, memory works by its own rules, and the most honest thing writers can really do is report on them, follow their leads.

‘Still Pictures: On Photography’ by Janet Malcolm is published by Granta Books.

From the April 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

What the dismantling of USAID means for world heritage