There are many different kinds of museum directors. Some are essentially scholars, others bureaucrats. A third group belongs to those who are by nature collectors – or would be if given half a chance. Firmly in the acquisitive camp, though no negligible art historian himself, is Dr Kjeld von Folsach. As director of the private Davids Samling (David Collection) in Copenhagen since 1985, he has certainly been afforded the kind of opportunities that most of his peers could only dream of. As a result he has transformed his institution into one of the greatest Islamic art museums in the world.

It is, of course, easy enough for any collector – private or institutional – to acquire works of art, as long as funds are available. The difficulties lie in choosing the right ones, and in understanding how best to present and interpret them. Sound scholarship is no prerequisite for a good ‘eye’ – and there are plenty of art historians out there without one. What is so striking about the Davids Samling, which was expanded and remodelled from 2005–09, is that in von Folsach’s unashamedly connoisseurial approach almost every piece more than justifies its place and holds its own in installations that are as dramatic and beautiful as they are illuminating. This gem of a small museum deserves to be far better known.

The Davids Samling began life as a museum in 1948 and its collection was built around the 18th-century European decorative arts and 19th-century Danish paintings beloved by its founder, the prominent lawyer and collector C.L. David (1878–1960). His early 19th-century townhouse on Kronprinsessegade and the neighbouring no. 32, which was acquired by the C.L. David Foundation and Collection in 1986 in order to house a growing collection, overlook the gardens of Rosenberg Castle in the centre of the city. There is a festive air when I visit during the hottest September for a century – the gardens opposite are strewn with sunbathers and picnickers and the banners for the Davids Samling and its current ‘Shahnama’ exhibition flutter in the breeze.

I meet the lively von Folsach in his office overlooking the park at no. 32 to discuss the evolution of the collection, his collecting strategies and the increasingly pertinent – and sometimes contentious – role of an Islamic art collection in contemporary culture.

Portrait miniature of Sultan Ibrahim Adil Shah II of Bijapur (c. 1590), India, Deccan, Bijapur. David Collection, Copenhagen

The roots of the Islamic collection, he is quick to point out, predate him. Emil Hannover (1864–1923), a former director of Copenhagen’s then museum of decorative arts – an institution which, since it changed its name to the Designmuseum Danmark, has tripled its visitor numbers – liked to apportion different responsibilities to individual private collectors in the hope that their holdings would end up in the museum. He persuaded Mr David to collect Islamic works of art which were not represented in any Danish museum. ‘He did,’ von Folsach grins, ‘but I can’t say it was with any enthusiasm. When he [David] died in 1960, the Foundation appointed my predecessor André Leth, and it was he, in collaboration with the trustees, who decided that the David Collection should not be just another house museum with a pretty installation of a kind you see everywhere.’ During Leth’s tenure (1962–85), half of the collection’s acquisition funds went on Islamic art, the other half on rounding off the European collections.

‘When I took over in 1985, I had the clear directive from my board that we should concentrate even more on Islamic art. Although I knew nothing about it, the idea did not frighten me – I thought it was a challenge,’ von Folsach enthuses. ‘The question was whether to focus on particular areas or not. We were, for instance, much stronger in Persian than in Arab or Islamic art from Spain. In the end it was my decision – slightly against the preference of the trustees – that we should try to become encyclopaedic so that the collection could be used in context with teaching at the university. So the collection we have today covers all aspects of Islamic art but we do consider ourselves first and foremost an art museum, and aesthetic qualities are of paramount importance to us.’

‘That means that there are certain areas in which we do not collect. We do not collect simple pottery from the villages, for instance, or the art of the nomads, and we are not buying unillustrated manuscripts – text rather than expression,’ he tells me. A conscious decision was also made to exclude the art of sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia – ‘too different from the rest’ – and art after 1850, which von Folsach firmly believes should be seen in the context of international modern and contemporary art.

On his first international trip as director he met Michael Rogers, then a curator at the British Museum, and asked him whether he should plunge into the languages of the Islamic world. ‘He recommended me not to, pointing out that after a decade I would only speak one of them like an 11-year-old child. He advised me to concentrate on what I was good at. We have been lucky over the years to have a young visiting scholar – Will Kwiatkowski – who is brilliant at languages, and if he cannot read something, he knows someone who can.’

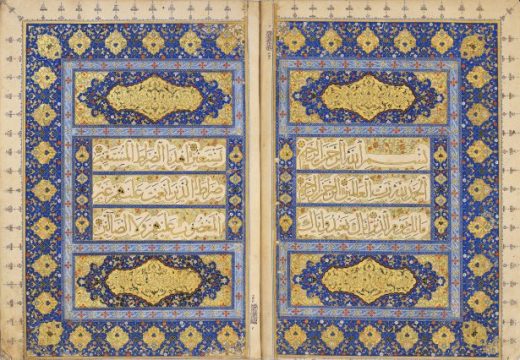

Von Folsach began by discreetly looking to fill gaps in the collection. ‘There was only one piece here from Muslim Spain, and we were quite weak in painting and very weak in calligraphy, and while calligraphy is not the thing closest to my heart I do realise its importance in Islamic culture. In this field I decided to play it safe – buying pages from famous Korans like the celebrated Blue Koran. You could argue that these were not very imaginative purchases but I have been more inventive in other areas where I could trust my own instincts more.’

Casket (c. 966–68), Spain, Cordoba. David Collection, Copenhagen

In over 30 years he has experienced ever-changing patterns in the collecting of Islamic art. ‘At the beginning, the Arab buyers were very strong. Then Mr [Nasser David] Khalili started to collect in a way quite different to others, and then Sheikh Saud began hoovering up whatever he could of great objects. All of these buyers have left only little pieces for us.’ I protest at his modesty, and quite rightly. ‘Our best piece, I would say, is the fantastic Cordoban ivory casket made for the Spanish Umayyad court around 966–68 and showing all kinds of semi-symbolic scenes of hunting and power. Perhaps the only example of better quality is the Pyxis of al-Mughira in the Louvre, but this casket is more monumental. Of course it was first offered to Sheikh Saud – he realised his mistake too late and turned it down. So even in a very strong market there is potential – and a very strong market brings out very wonderful works of art.’ This piece came from a Rothschild collection.

‘I would say that the period when the Sheikh was buying for Qatar was the most dispiriting period for me as a buyer. It was always hard for me to persuade my board that we should be prepared to pay ten times the estimate published in a catalogue of a serious auction house, but even then Sheikh Saud would just bid on.’ He pauses, brightening: ‘On the other hand, it helped my reputation in the eyes of my chairman because he could see that I was not a complete idiot.’

He will not be drawn on the size of the Foundation’s well-invested endowment but does concede that it is probably larger than it was during Mr David’s lifetime. ‘We are rich but not in international terms, or even as rich as many other Danish cultural foundations, but it would be a very bad year if we could not bring at least one masterpiece to the collection.’ Normally they never acquire entire collections – ‘I want every piece to fit’ – but in 2006 they added around 180 Persian paintings from the Benkaim Collection; most years, however, it is about 20 objects.

Their agility as an institution has also been a keen advantage. ‘If I am offered something by a dealer I will usually have an answer from my board in three or four days and the money would be paid immediately,’ explains von Folsach. ‘Most large museums have a long acceptance procedure and then they have to find the money. As for private collectors,’ he pauses to find a tactful phrase, ‘some of them never pay or return an object after six months.’ The Davids Samling chooses not to deaccession: ‘It is dangerous when museum directors start selling things they are not personally interested in.’

Medallion (first half of 14th century), Iraq or western Iran. David Collection, Copenhagen

One major change has been the institution’s attitude to acquiring works of art without a watertight pre-1970 provenance outside their source country. ‘Although the UNESCO convention on the illicit traffic of cultural property was in place when I began, there was a generally more relaxed attitude to buying unprovenanced objects. If we were assured that something came from a perfectly good source, then we would probably accept it. That is no longer the case, but it did allow us to buy things that we had never seen before and we have not seen since.’

He cites the apparently unique tapestry roundel from early 14th-century Iraq or Iran. At first, everyone thought it was a fake – I thought it looked like a cushion-cover that a German housewife might have made for Otto von Falke’s 70th birthday. Then it came here and I looked at it under a microscope and realised that what looked like brown thread was in fact gilded animal gut spun around cotton which would have been all but impossible to fake. We had it carbon-14 tested and it came out exactly to the period I had placed it art historically.’

‘This was a period when a lot of fabulous textiles also came out of Tibet,’ continues von Folsach, ‘and although we have not been able to buy on as grand a scale as Cleveland or the Abegg-Stiftung, for example, we have still been able to acquire magnificent textiles which are one of the greatest treasures of medieval Islam. I suppose if I had been a curator in the British Museum, I would not have been able to buy these things and perhaps I would hesitate to buy them today, but I am very pleased that I did. Here they are preserved, published and accessible to the entire world on our website. I cannot feel too guilty.’

Rosewater sprinkler (second half of 12th century), eastern Iran or Afghanistan. David Collection, Copenhagen

A favourite piece he admits that he would not buy now is the astonishing and technically complex brass rosewater sprinkler from 12th-century Iran or Afghanistan, bearing bands of repoussé lions and birds in incredibly high relief. Nearby is possibly the earliest piece of Islamic furniture in the world, a little wooden hexagonal table dating to the 11th or 12th centuries apparently found in a cave in Afghanistan and which came to the museum in pieces in a plastic bag. ‘Again a story I am proud of but should not be.’

Von Folsach is keen to emphasise that interesting things are not necessarily expensive, leaping to his feet to illustrate the point by picking up a glass carpet weight from a table beside his desk. ‘I would not say this was extraordinary but it is a type of glass from India that I have never seen before and I think it is a very sexy little object. It is very abstract but you can still see the flowers that you find in the much more refined earlier pietra dura work.’ As von Folsach speaks, he is weighing the tactile glass in his cupped hands and caressing its surface. When I point this out he laughs: ‘Most people can only look at objects in a museum but I have fondled all of them. I love this contact.’ It is a feel for objects that began during his childhood in remote northern Jutland, where his own ‘museum’ consisted of a series of shells, snails, insects, fish, butterflies, Stone Age artefacts, and even old farm utensils.

Hexagonal table (11th–12th century), Afghanistan. David Collection, Copenhagen

Returning to the subject literally in hand, he frowns slightly: ‘A trained Islamic art historian was as rare as a coelacanth in the 1960s. Now we have professors all over the place generating two or three doctoral students each year, but these Islamic art historians are becoming ever more theoretical. I understand this is needed to bring the field closer to what is going on in European art history but many of these young people have never had the opportunity to handle a pot. I hope that some of them will turn out to be great objects people.’

Von Folsach’s passion for objects is evident as we walk around the Islamic collections which, since the remodelling, have expanded over two floors of both the listed buildings. Here light levels suddenly drop. In part this is to allow for the dynamic and resonant mixture of all media – textiles, works on and of paper, woodwork, glass, ceramics, stone and metalwork – but also to highlight the objects themselves, glowing against rich, deeply coloured walls. However striking the display, the museum is committed to telling a narrative of Islamic art through its 20 galleries devoted to historical periods and geographical areas, with additional galleries dedicated to textiles, calligraphy and painting, and another to techniques.

Coins, usually isolated and condemned to oblivion in separate galleries, here provide the historical framework for every room, their touch-screen displays containing a wealth of information about the dynasties and periods in which the surrounding works of art were made (further information is available on every exhibit in English and Danish through the iPad label-reader that visitors are given on entry to the museum, also free). Von Folsach is rightly proud of the fact that two-thirds of the collection’s 3,500 objects are on display – considerably more than at the British Museum, ‘and I would not say the quality of ours is much lesser’.

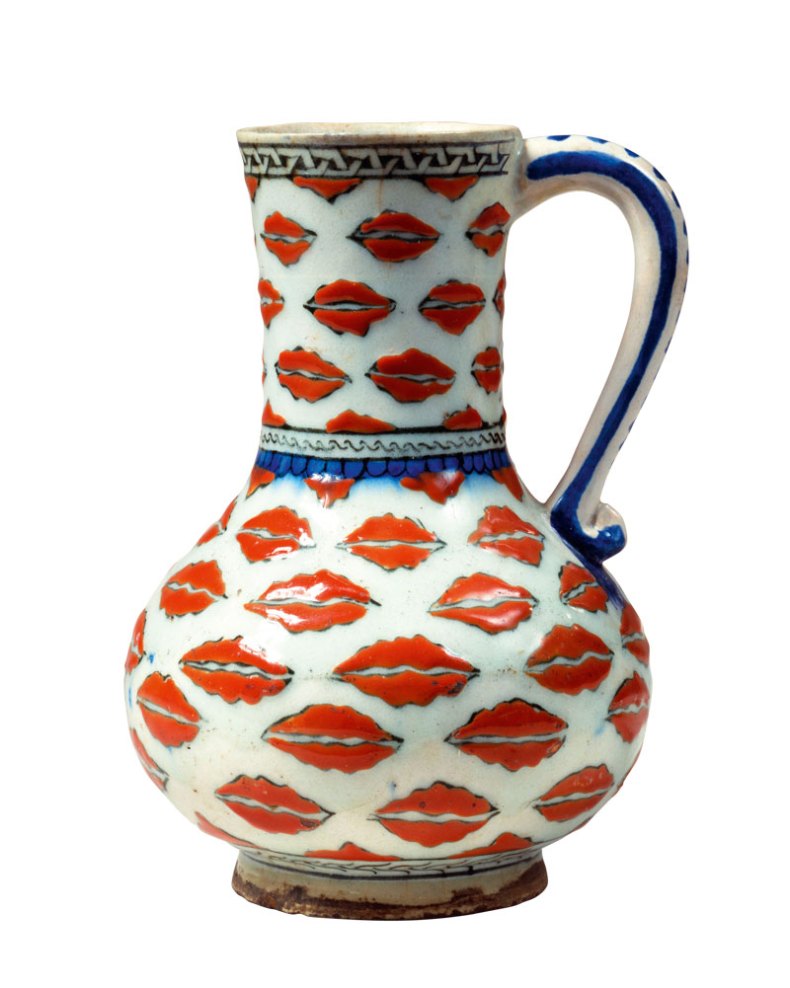

Jug (c. 1575), Turkey, Iznik. David Collection, Copenhagen

Key to all is the introductory wing which offers a cultural and historical background to Islam, and is of use not only to schoolchildren and people of other faiths but to Muslims too. ‘When this collection began, no one thought that Islam would be on everyone’s lips, or could have imagined that there would be 100,000 Muslims in Copenhagen. While our visitor numbers have risen from around 10,000 visitors a year to around 50,000, interest from this sector of the population unfortunately remains low. Those who do come are surprised to discover that Spain had a great Muslim culture, for instance, and to see things they thought were forbidden in the Koran or at least by the mullahs.’ He cites images of wine-imbibing princes and quotations about lips as red and delicious as the finest Shiraz.

Self-censorship, however, is not on his agenda. ‘Earlier this year I was astonished to discover that the V&A had taken an Iranian image of the prophet Mohammad off their website. I cannot understand that and I have to say that I do not want to. We are respectful and we try not to offend anyone but we cannot allow our displays to be influenced by contemporary attitudes.’ He continues: ‘Next year we will stage an exhibition around the representation of man in Islamic art. Many say there are no such images but that is absolute nonsense – there are billions of them – and the show will include depictions of the prophet too. These paintings were commissioned by the likes of the Ottoman sultans who also happened to be the caliphs of the Sunnis. What is the problem?’

From the November issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Suzanne Treister’s tarot offers humanity a new toolbox