In a small museum on the rugged coast of north Cornwall resides a notable collection of objects associated with the occult. The director of the Museum of Witchcraft and Magic (MWM), Simon Costin, talks to Apollo about the rising interest in the supernatural.

What is the Museum of Witchcraft and Magic, and where is it?

The MWM is a collection pertaining to magical practice not just in the United Kingdom, but all around the world. It makes reference to the magical practices of other cultures by drawing comparisons between what happens here and what happens elsewhere. It [includes] over 4,500 objects and 9,500 manuscripts and books. It’s the largest collection of such items in Europe and probably the largest occult library in Europe, too.

We have an artist residency and a temporary exhibition space where we mount a new show each year. The current exhibition is work by the artist Lisa Ivory; topics they’ve previously explored include [the 17th-century Scottish witch] Isobel Gowdie and Cornish folklore.

[The museum] is located in north Cornwall, in a small harbour village called Boscastle. The building was an old pilchard-pickling factory back in the 1930s and ’40s; it’s a heritage building with narrow corridors – we can’t install anything like a lift – and lots of character.

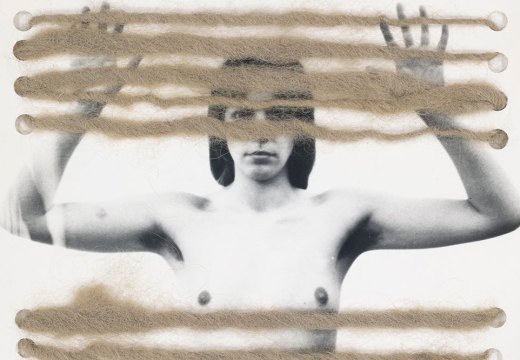

Inside the Museum of Witchcraft and Magic, Boscastle

How did it come into existence?

The museum was set up by a man called Cecil Williamson. He was a fascinating character who lived many lives: he was a spy for MI6, a film producer, an occultist and a collector. Williamson first founded a Museum of Witchcraft in Stratford-upon-Avon but after local opposition (including a firebomb and a dead cat nailed to the door), he moved to the Isle of Man and in 1951 opened the Folklore Centre of Superstition and Witchcraft. He installed a friend, Gerald Gardner, as its ‘resident witch’.

Gardner had written a novel called High Magic’s Aid (1949) that contained a lot of occult practice. He was also propagating a new religion called wicca, which later became known as ‘Gardnerian wicca’. [Williamson and Gardner] were both very strong characters who had their own collections of occult objects. After a period of about five years, they parted company and Williamson returned to the mainland to reopen the museum elsewhere. He eventually settled in Cornwall and opened the museum here in Boscastle. In 1996, he sold the place to my predecessor, Graham King, who helped develop it into a successful independent museum.

How did you come to be the director of the MWM?

I had always wanted to visit but hadn’t been able to. It’s in quite a far-flung place and I don’t drive. In August 2004, I turned on the news and saw the terrible flash floods that had hit Boscastle – I assumed the museum was no more. But thankfully Graham was also a coast guard, and he knew that something was seriously wrong about an hour before the waters hit the building. He used that time to move as much as he could to the top floor; as a result not much was lost from the collection. I kept ringing the museum, hoping there was something I could do. Eventually Graham called me back to say that unless I had dozens of antique display cases to replace those that were damaged, he wasn’t sure I could help. It just so happened that a friend of a friend of mine was decommissioning all the Victorian display cases at the Geological Museum [in London]. I acted as a go-between and we became friends. Eventually, when he was looking to pass on the reins, Graham asked if I would be game to take the museum on. At that point, I was director of the Museum of British Folklore (I still am). I thought about it for all of two seconds and said yes. That was in 2013; this is my tenth year.

What is the mission of the MWM?

We aim to represent the diversity and vigour of magical practice respectfully, accurately and impartially, through entertaining and educational exhibitions drawing on cutting-edge scholarship and the insights of magical practitioners. That’s it in a nutshell.

During my tenure, I’ve wanted to raise greater awareness of the collection among the museum fraternity. I’m very pleased with how that’s worked – none of them had heard of us before I took over. We now loan objects all over the world; it’s been a key part of what I do as director. Due to the enormous increase of interest in witchcraft and the occult in general, many museums are hunting around for objects to complement their exhibitions, and we are the be-all and end-all for magical items.

Simon Costin. Photo: Crista Leonard

In your opinion, what’s the reason for the rise in public interest in the occult?

There are many different strands feeding in. Young people, in particular, are looking for a spiritual dimension to their lives – one that doesn’t come from an organised religion. The ecological movement is also adding to the growing interest in witchcraft, because witchcraft is very much rooted in seasonal changes and in Mother Nature. Then there’s the increasing number of nature writers within the last 10 years – think of people like Robert MacFarlane or the Dark Mountain Project. We’ve noticed many more young women reclaiming the word ‘witch’ as a form of empowerment – think of ‘Hex the patriarchy’ and all those terms that have come about. It’s also been fed by the rise of social media. #WitchTok has 40 billion hits or something ludicrous like that.

Who visits the MWM?

Tourists passing by make up about 70 per cent of our visitors, because we’re on the trail of Boscastle to Tintagel to Padstow. The other 30 per cent range from academics to practitioners. We’re up to about 51,000 annual visitors, which for a small museum is extraordinary. In summer, we’re at capacity here. When people say, ‘We’d love to do this project to advertise your museum’, we have to be like ‘No, no, we don’t want any advertising!’ We also have demands on our time from academics wanting to come and use the library. We’re a very small team – to keep all the plates spinning is quite a feat.

How does the museum fund itself?

We’re independent and we aim to remain so. The minute you become publicly funded, there are so many hoops you have to jump through and you lose autonomy. We’ve managed to keep going on our door takings, basically.

Weighing chair (early 1700s). Museum of Witchcraft and Magic, Boscastle

Which object from the collection gets the most comments from visitors?

People always have the most visceral reactions to the curses. Some people, if they’re particularly sensitive, report feeling faint or nauseous. The difference between a museum that contains magical objects and, say, somewhere like the V&A is that a lot of these objects have been used in ritual practice over generations. So they’re still very much alive, if you like.

Curses are a form of sympathetic magic – a poppet, as it’s called, is often formed in the likeness of the individual who is to be cursed. In popular culture (for example, in horror films), they are usually made of wax and contain hair or nail clippings, something belonging to that person. But they can also take other forms – an item of clothing can be taken from the person being cursed, say. But this conception that witches are evil and always doing bad things is totally erroneous. They can heal as well as harm. So a poppet can also be made to in the form of a person who’s ill, for instance, and washed in curative herbs or doused with healing oils.

One of our star objects is a weighing chair from the early 1700s. It’s an iron chair that looks something like an upright cradle on one side and on the other side is a Bible. After the period of the prosecutions, when authorities were keen to disprove the practice of witchcraft, they would say, ‘Okay, you’re accusing this individual of being a witch. This man or woman, if they weigh less than the Bible, they’re a witch.’ And of course, nobody weighs less than a Bible. Every time a judge would get this device out, the person would be found not guilty. So it was a positive device, used by the authorities to disprove the practice of witchcraft. It was loaned to the Ashmolean Museum for their exhibition ‘Spellbound: Magic, Ritual and Witchcraft’ (2018–19).

How is Halloween marked at the museum?

We don’t mark it; we’re all shattered by the end of the season. There was a group who organised something called the Dark Gathering, which happened in the harbour outside the museum for some years. But there were health and safety concerns – it’s not lit at night and 700 people turned up to the last one, so it’s moved to Tintagel. It’s even bigger now, which is a real indication of the level of interest.

The Museum of Witchcraft and Magic is open from 1 April until 31 October every year in Boscastle, Cornwall.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Pilgrims’ progress? The Vatican Jubilee has frustrated Romans and tourists alike