From the November issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here

Who was the greatest artist of the 20th century? A teacher once asked this question in a class I was taking. Half the room answered Duchamp, the other half Picasso. I remembered this question while taking in the Museum of Modern Art’s magisterial survey of Picasso’s sculpture. If Duchamp was the ego of the 20th century, than Picasso was the id – intuitive, sensual, impulsive. And yet the show reveals that Picasso may have been more in tune with Dada than history suggests.

Unfolding chronologically and episodically, dividing Picasso’s works into sections based on his location, collaborator, or muse, the exhibition delves into the artist’s life. It slowly reveals the compulsive personality who lived to make things (4,500 in total and some 700 sculptures, according to the exhibition catalogue), and thus did not always take himself or the things he made terribly seriously. Picasso rarely exhibited his sculptures and liked to keep them close.

The show opens with several sculptures made from wood. The origin story of Picasso’s visit to the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris and its result in his making the landmark Les Demoiselles D’Avignon (1907) is well known; less known is that the show also encouraged him to take up wood-carving. Influenced by African and Oceanic sculptures, Picasso whittled pieces of wood into jagged figures, moving sharply away from realism. What did he see in primitivism? Aside from a raw, talismanic quality, he appreciated the way that the anonymous artists worked with their material, rather than forcing it to describe an object perfectly. (He shared this appreciation with Matisse, who introduced him to African sculpture.) A plaster apple from 1909 is composed of a series of ridges and angles; it looks as though it were hurtling through space, blending futurist speed with cubist deconstruction of perspective.

Glass of Absinthe (Paris, spring 1914), Pablo Picasso © 2015 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The next section explores the cubist years, from 1912 to 1915, and is the location of an enchanting assortment of Picasso’s absinthe glasses, in a bronze edition of six from 1914. Just a year earlier, Duchamp had stuck a bicycle wheel into the seat of a stool and declared it art. Picasso was also experimenting with found objects: he bestowed each absinthe glass with its own absinthe spoon, atop of which rests a bronze sugar cube. The bronze ‘goblets’ sway and twist woozily, each painted with a spritz of polka dots or vivid swathes of colour. As the curators are quick to point out in the show’s extensive catalogue, Picasso used real-life objects more as visual metaphors than Duchampian readymades, but both artists capitalised on a growing understanding that the rift between ‘art’ and ‘life’ was shrinking.

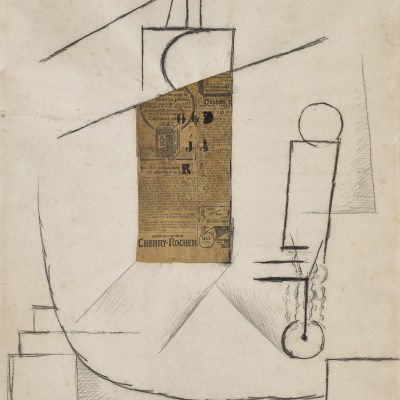

This period was also when, in 1912, Picasso assembled a totally convincing guitar from cardboard, string, and paperboard, and then two years later recreated it in sheet metal, causing his friend André Salmon to wonder: ‘What is it, painting or sculpture?’ At the time, and even today, the definition of ‘true’ sculpture is that it should exist in the round (or on a pedestal), yet both Guitars persuade viewers to reassess these terms. In his readiness to discard traditional methods and pick up whatever objects happened to be lying around that might serve his purposes, he abandoned categories and convention, becoming a post-media artist avant la lettre.

As soon as he mastered one style, he moved on to another, this restlessness captured by his jittery iron-wire sculptures, composed in response to a request for a monument to his friend, the writer Apollinaire. (None of his proposals were accepted.) The culmination of these many attempts is Woman in the Garden (1929–30), a seven-foot-tall assemblage of scrap metal painted white, which resolves into an image of a figure wandering among immense tropical plants. Picasso worked on this and several sculptures at this time with his friend, the metalworker Julio González, who enabled him to work on a larger and more ambitious scale.

In 1930, Picasso purchased the Château de Boisgeloup outside Paris, where he had ample space to make work as large as he liked. For the next several years, he experimented in plaster, making rounded, sensual figures such as Head of a Woman from 1932, considered by many to be one of several representations of his secret mistress, Marie-Thérèse Walter. He continued to experiment with found objects as material, using cardboard to imprint a textured pattern, or using screws and nails to stand in for body parts. When his then-wife, Olga Ruiz-Picasso, got the property as a result of their separation agreement in 1936, Picasso moved back to Paris. He remained in the city during the German occupation, despite being deemed a ‘degenerate’ artist by the Nazis, working in his studio bathroom (it was the only room with heat), churning out numerous animals and figures, such as Man with a Lamb in 1943, a poignant composition of a male figure protectively cradling a lamb, made in a single day. Ever active, when he wasn’t sculpting or painting, he was ripping amusing shapes from paper, such as a small dog for his mistress, Dora Maar, after her lapdog disappeared. This seemingly tossed-off work, along with similarly made shapes of a skull and goat, appear surprisingly contemporary in our age of ‘deskilling’.

Vase: Woman (Vallauris, 1948), Pablo Picasso © 2015 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The show climaxes with the cheerful ceramics and raucous assemblages of the late 1940s and 1950s. Here his penchant for incorporating junkyard finds into his work comes full circle – the claws of a bird from 1958 are made from forks; a series of tall bathers, arranged in a group as though watching the waves roll in at the beach, come magically to life, made merely from stray pieces of wood. During this period, Picasso was also working on public art, such as the immense sculpture in Daley Square in Chicago, supposedly a portrait of his mistress at the time, and which is represented here by maquettes. Yet it is the smaller, ad hoc pieces, that have more impact, pushing aside the mantle of ‘genius and ‘master’ and allowing viewers a close look at one man’s restless, antic creativity.

‘Picasso Sculpture’ is at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, until 7 February 2016.

—

Catalogue by Ann Temkin and Anne Umland (eds.), ISBN 9780870709746 (hardback), $85 (Museum of Modern Art).