The Aga Khan IV, who has died this week at the age of 88, was the spiritual leader of the world’s Ismaili Muslims, a sect of Shia Islam. His love of horse racing and his entrepreneurialism in business is well-known, but the late Aga Khan also directed some of his fabulous wealth to cultural heritage projects in, for example, Cairo, Delhi and Kabul, and to promoting a greater understanding of Islamic culture. In Toronto, the Aga Khan Museum opened in 2014 as a permanent home for his important collection of Islamic art. In 2007, the year of his 70th birthday, Prince Karim Aga Khan IV was Apollo’s Personality of the Year, and profiled by Lucian Harris.

Religious leader, philanthropist, diplomat, horse breeder, business tycoon, jet-setter, patron of architecture and heritage preservation: at 70 years old, Prince Karim Aga Khan IV is many things to many people. Currently celebrating his 50th year as Imam or spiritual leader to a global community of around 20m Ismaili Muslims, the Aga Khan may be a familiar figure in the winners’ enclosure at Epsom or in paparazzi photographs on the Costa Smeralda, yet he remains an extremely private person, leading a life that few understand well.

He assumed the Imamate on the death of his grandfather in 1957. The title was synonymous with fabulous wealth, luxury and glamour, not least thanks to the exploits of his father, Prince Aly Khan, whose marriage to Rita Hayworth and taste for fast cars and fast women contributed to his being overlooked in the succession.

The twice-married – and currently single – Aga Khan has continued many of his family’s traditional interests. Not only is he a major breeder of racehorses at his Aiglement estate in France but, like his grandfather, who served as President of the League of Nations, he has assumed an important role on the world stage. This has been manifested primarily through the activities of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), an umbrella group that co-ordinates a wide range of agencies and projects. With a presence in 27 countries employing 57,000 people, it is one of the largest private development organisations in the world.

Culture has long played a key role in the Aga Khan’s activities. Together with economic and social development, it is one of three main areas covered by the AKDN, which is structured to reflect the Aga Khan’s belief in the interconnectedness of many of its goals. In this context the cultural programmes carried out under its aegis are widely framed as tools of social reform, either directly linked to the economic regeneration of some of the poorest Muslim communities, or designed to encourage better understanding of the cultural achievements of Islamic civilisations.

Nevertheless, according to Luis Monreal, the director of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKCT), the body which administers all his cultural activities, the Aga Khan has been very careful to keep a clear division between his role as Imam of the Ismaili community and the work for the AKDN, which maintains a secular front despite its deep involvement in the Islamic world.

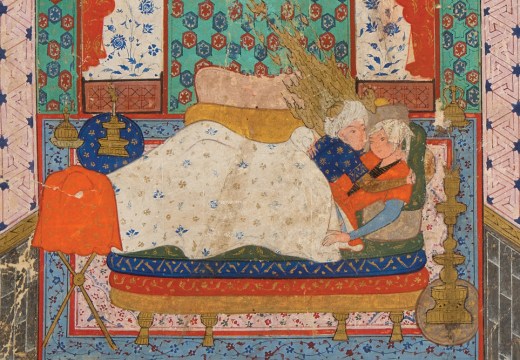

The main projects administered by the AKTC include the Aga Khan Award for Architecture – a flagship endeavour established in 1977 – the Historic Cities Support Programme; the Museums Project; the Music Initiative in Central Asia; and the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture, with its online presence Archna. This year, a series of exhibitions in Parma, London and Paris presented highlights of a collection of Islamic art that will find its permanent home when the Aga Khan Museum opens in Toronto in 2010. On display were many star lots from recent London auctions, purchases that revealed the extent to which the Aga Khan has become a major presence in the Islamic art market. ‘His Highness owns and appreciates beautiful objects from all cultures and is as interested in European art as he is in Islamic art,’ says Benoît Junod, head of the Aga Khan’s Museum Support Unit. ‘But he is not an obsessive collector like his uncle Prince Sadruddin, who would never miss a sale.’

‘He has a notion that in the west there is still an incredible ignorance of the cultural achievements of the Islamic world and that the best way to bridge this gap of understanding is through education,’ adds Junod. ‘He sees that objects can be the carriers of a non-textual message, allowing a glimpse into a Muslim world that is very different from that which we see on television.’

The Aga Khan Museum in Toronto opened in 2014. Photo: Lachance/Toronto Star Nick Lachance/Toronto Star

For London, the exhibition ‘Spirit and Life’ gave a taste of what could have been if the Aga Khan had not failed in two attempts to secure sites for the museum in the British capital. In 2002 an offer of £24m for a disused part of the St Thomas’s Hospital on the Lambeth Embankment fell foul of local opposition, as did another proposed site next to Tate Britain. Frustrated, the Aga Khan switched his focus to Canada, where a large Ismaili community has lived since the 1970s.

The 10,000-square-foot museum by Pritzker-Prize-winning Japanese architect Fumihiko Maki will share a seven-hectare site with a new Ismaili centre by veteran Indian modernist Charles Correa. When it opens it will be the first dedicated museum of Islamic art outside the Muslim world.

‘Building the collection for the museum started in earnest around six or seven years,’ says Monreal. Initially it was with the assistance of the Aga Khan’s brother Prince Amyn as well as his uncle Prince Sadruddin, a passionate collector of Persian, Arabic, Indian and Turkish miniatures, and manuscripts since the 1950s. His highly important collection of the arts of the Islamic book was acquired for the museum shortly before Prince Sadruddin’s death.

With Sheikh Saud al-Thani of Qatar spending limitless amounts on treasures for the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, which opens next year, the past decade has not been the easiest time to build a high-quality collection. Nevertheless, the Aga Khan has continued to buy discreetly and astutely. ‘The range of material is impressive,’ says Sheila Canby, curator of Islamic art and antiquities at the British Museum. ‘The Aga Khan appears to appreciate these objects not only as works of art but also as touchstones of the material culture of the Muslim world in earlier centuries.’

The collection covers all the major Islamic civilisations, with a particular focus on areas related to the Aga Khan’s religion and ancestry. The arts of the various Shia regimes that have ranged from Iran to India are well represented, including the Persian Qajar dynasty, whose ruler Fath Ali Shah first conferred the title of Aga Khan in the 19th century. However, it is the Fatimid caliphate, a Shia Ismaili dynasty that ruled much of North Africa and North Africa and the Middle East between the 10th and 12th centuries, that is perhaps the most important reference point for the Aga Khan, who traces his ancestry to Fatima, the daughter of the Prophet Muhammad.

The Aga Khan’s identification with Fatimid culture is also reflected in his wide-ranging involvement with the regeneration of the fabric of medieval Cairo, which was founded in 969 as capital of the Fatimid caliphate. The work there exemplifies a holistic approach that runs through the work of the AKTC, in which architectural restoration is linked with the improvement of social conditions and economically stimulating for-profit ventures.

In an interview with Philip Jodidio, published in a new book, Under the Eaves of Architecture – The Aga Khan: Builder and Patron, the Aga Khan describes how his interest in architecture was stimulated by visiting impoverished communities in the 1960s. ‘It was driven by the question of what to do to improve the quality of life of the ultra poor,’ he says. ‘Architecture is the only art that is a direct reflector of poverty […] in it there is an inherent and unavoidable demonstration of the quality of life or its absence.’

The work in Cairo arose from a 1984 scheme to provide the Egyptian capital with much-needed green space. The result was the creation of Al-Azhar Park, which was finally completed in 2005. This $30m transformation of a 30-hectare former municipal rubbish dump in a depressed area close to the citadel was the first of a series of AKTC-funded projects to regenerate this historic part of the city. These included the excavation and restoration of the original walls of the fortified city built in the late 12th century for the Ayyubid ruler Salah al-Din (Saladin), as well as the recently completed restoration of two medieval complexes in the Darb al-Ahmar district: the 14th-century Umm al-Sultan Sha’ban mosque and the Khayrbek complex, which encompasses a 13th-century palace, a mosque and an Ottoman house. At the inauguration ceremony, the Aga Khan explained that the project had given him ‘a profound sense of connection with my own ancestors’.

Cairo is also the location of the second of the Aga Khan’s three major museum project (the third is the Indian Ocean Maritime Museum in Zanzibar). At the north end of Al-Azhar Park the AKTC is building the Museum of Historic Cairo in collaboration with the Supreme Council of Antiquities of Egypt. The museum, which will house artefacts drawn from the reserves of other collections in Cairo, will be part of the Urban Plaza, a mixed-use complex.

Prince Karim Aga Khan IV laying the foundation stone of the country’s first sunken museum at the site of Humayun’s Tomb site in 2015 in New Delhi. Photo: Ajay Aggarwal/Hindustan Times via Getty Images

Another country in which the Aga Khan has extensive ongoing cultural projects is Afghanistan. In Kabul, the AKTC has focused on historic districts in the old city threatened by unscrupulous development. The most high-profile project has been the restoration of the war-damaged Bagh-e Babur, the 16th-century gardens and tomb of Muhammad Zahiruddin Babur, founder of the Mughal empire in India. The project, carried out with the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, was completed in 2006. The Aga Khan has also funded the restoration of the late 18th-century mausoleum of Timur Shah, the ruler regarded as the founder of modern Afghanistan.

While projects range from northern Pakistan to Zanzibar, the Aga Khan’s presence in the field of cultural heritage is not exclusively devoted to the Islamic world. He has recently collaborated with World Monuments Fund (WMF) to undertake various renovations on the estate of the château of Chantilly, close to his home at Aiglemont in France.

According to Bonnie Burnham, president of the WMF, which has worked with the AKTC on many projects, the Aga Khan’s cultural programmes are unique because of the way that he approaches each one through a deep understanding of the basic social and economic conditions, working up to engage with the whole project on the appropriate level: ‘They really are very broad-based and visionary. There are not many institutions that have the capacity to do this. He is incredibly energetic. He really does seem to have his finger on the pulse of life in the global Islamic community embracing every sect and manifestation of culture and he’s interested in all of it.’

From the December 2007 issue of Apollo.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

The Mughal emperors who forged a new artistic tradition

The Mughal emperors who forged a new artistic tradition

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

How artists respond to disaster