Peering through the holes of a pierced canvas by Lucio Fontana, one glimpses a dark space where one knows a wall to be. What must it be like in that narrow yet seemingly infinite space behind the stretcher? Fontana himself provided an answer in his Ambienti Spaziali (Spatial Environments), a continuation of his spatial experiments with canvas. He produced 18 site-specific installations between 1948 and his death 20 years later, yet all but one have been destroyed. At HangarBicocca, in the most ambitious project of its kind to date, 11 have been reconstructed.

Strictly speaking, only nine are Environments. Fontana called the two imposing neon ceiling installations that feature here Structures as they illuminated and transformed open architectural spaces. The two ceiling pieces, a looping lyrical white neon gesture originally designed for the staircase at the IX Triennale di Milano (1951) and a sea of green and blue neon stripes for the Esposizione Internazionale di Torino (1961) are positioned at either end of HangarBicocca’s enormous hall. This refreshing luminous bath is practical as well as pleasurable, lighting the path between the series of closed rooms.

Struttura al neon per la IX Triennale di Milano (1951/2017), Lucio Fontana. Installation view at Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan, 2017. © Fondazione Lucio Fontana. Photo: Agostino Osio. Courtesy Pirelli HangarBicocca

Each room has been diligently based on the dimensions of the original sites. Fontana’s first Environment was exhibited in Galleria Del Naviglio in Milan in 1949: the artist suspended from the ceiling a biomorphic form, painted in fluorescent colours and illuminated only with UV light. Even those familiar with photographs of this installation may be surprised by the form’s sculptural complexity and its domination of the small space. The papier-mâché structure dates from 1976, when the architect Andrea Franchi recreated the installation for an exhibition in Bologna, but other Environments are reconstructed here for the first time.

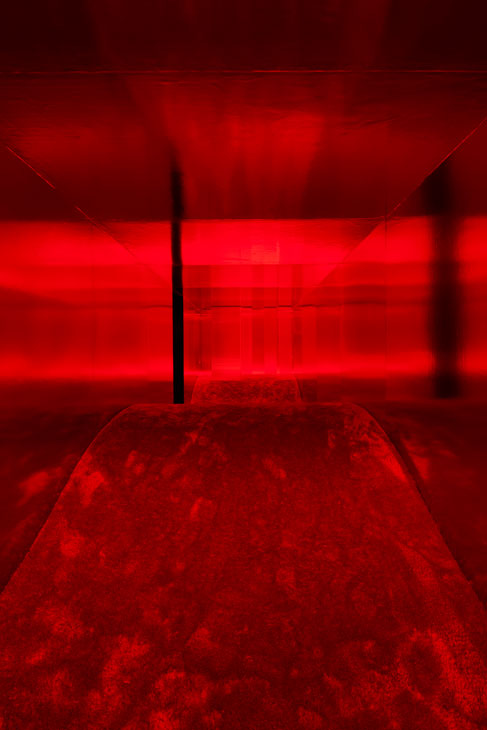

Of Fontana’s two collaborations with Nanda Vigo for the XIII Triennale di Milano (1964), the one never previously reconstructed, and here overseen by Vigo herself, is a revelation. A corridor with red metallic ceiling and walls, is illuminated by red neon light filtered through ‘quadrionda’ glass. An undulating floor, carpeted in soft red pile, forces one to stoop or even crawl to reach the exit. This physical, as well as sensorial, destabilisation recalls Japanese Gutai and anticipates conceptual and performative practices.

‘Utopie’, nella XIII Triennale di Milano (1964/2017), Lucio Fontana in collaboration with Nanda Vigo. Installation view at Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan, 2017. © Fondazione Lucio Fontana. Photo: Agostino Osio. Courtesy Pirelli HangarBicocca

The same can be said of the Environment made for Fontana’s exhibition at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis (1966), here also restaged for the first time. After entering through a short, dark tunnel, the visitor sinks into the soft rubber floor. The black walls are punctuated by small lights, which seem to cut a rectangle through the space, creating an intangible barrier, obliquely recalling the artist’s Little Theatres. Fontana’s ongoing project to meld dimensions is writ large.

The show includes four more Environments that were realised outside Italy: three made for the Fontana exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam (1967) and one for Documenta 4 in Kassel (1968). These international projects increased both the works’ influence and the possibility of their recreation, as Fontana sent plans, which the curators here have carefully studied.

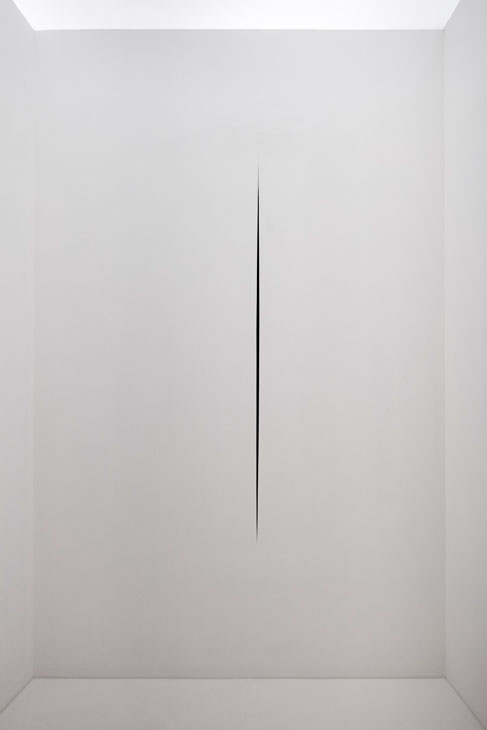

Ambiente spaziale in Documenta 4, a Kassel (1968/2017), Lucio Fontana. Installation view at Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan, 2017. © Fondazione Lucio Fontana. Photo: Agostino Osio. Courtesy Pirelli HangarBicocca

This philological care has led to some amendments to previous reconstructions. For example, the Kassel white labyrinth incorporating a single slashed canvas at its centre has not two entrances but three. The third one leads directly to the cut, while – in stark contrast – the thin wall separating it from the adjacent entrance creates a dark slice protruding between the brightly illuminated openings.

This exhibition is playful and pleasing. Yet its scale, ambition, and precision ensure it also illuminates Fontana’s spatial experimentation, emphasising his legacy in light and space from Flavin to Turrell, Kaprow to Miroslaw Balka’s Turbine Hall installation.

‘Lucio Fontana. Ambienti/Environments’ is at Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan, until 25 February 2018.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

The threat to Sudan’s cultural heritage