From the April 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

By the early 1970s Yoko Ono was probably the most famous visual artist alive. Yet such was the prejudice against her that she struggled to get exhibited. So, in December 1971, Ono took matters into her own hands. Without waiting for such trifles as a formal letter of invitation, she put up a sign announcing a show by the entrance of MoMA, took out an ad in the Village Voice and printed a catalogue – all for an exhibition that contained no work and was not officially taking place (she did release a pitcher full of flies out the back but it’s unclear how many entered the galleries). ‘It’s a conceptual show!’ a cameraman, Bob Fries, would explain to puzzled visitors outside the building. Their reactions, recorded in a short film shot by Fries, vary. ‘I think it’s a bit bonkers,’ says a woman with a Scouse accent and a grey bouffant. ‘Neato!’ exclaims a school-age boy in a green parka who totally gets it. ‘You can imagine it however you want!’

The Japanese musician and multimedia artist has been letting us imagine her work however we want for more than 70 years now. In the autumn of 1955, long before Sol LeWitt declared that ‘ideas alone can be works of art’, Ono’s Lighting Piece consisted of a simple injunction: ‘Light a match and watch till it goes out.’

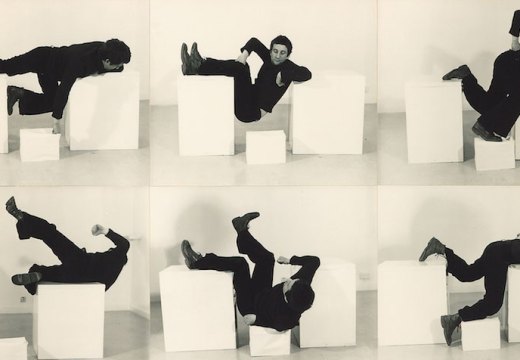

Yoko Ono performing ‘Lighting Piece’ (1955) at the Sogetsu Art Center, Tokyo, in 1962

Evidently it was an idea with legs. The first room of Tate Modern’s exhibition features three different realisations of that simple sentence: neatly typed on a yellowing index card from the typescripts of her book Grapefruit (1964); as a set of photographs documenting a performance in Tokyo in 1962, in which we see the artist hunched over on a piano stool smoking a cigarette; finally, as her first film, the single-reel FILM NO. 1 (‘MATCH’)/Fluxfilm No. 14 (1966), an extreme slow-motion close-up in which the actual ignition happens just off-screen but the bloom of flame and curlicues of smoke captured on grainy 16mm still have the capacity to seduce.

A wall text claims that the work was inspired by Ono’s childhood habit of flicking matches and watching them burn to distract her from bouts of misophonia. If so, the adolescent Ono would need a full box to get through ‘Music of the Mind’. Despite the titular suggestion of sounds mentally conjured in quasi-monastic quietude, all ten rooms of the exhibition are blaring with noise: phones ringing, toilets flushing, a recording of someone coughing, gallery-goers hammering nails into a canvas (for Painting to Hammer a Nail, 1961; Fig. 1). Ono’s works invite participation, but clearly there are limits to how much participation the gallery will tolerate. You’re welcome to play a game of chess on an all-white board with no black pieces, you can draw round your own shadow or pin your hopes to the leaves of an olive tree (‘I wish to choose the right boy to fall in love with,’ reads one; ‘FREE PALESTINE’ reads another), but you’re not allowed to climb the white ladder to read the tiny ‘yes’ painted on the ceiling for Ceiling Painting (1966).

Painting to Hammer a Nail (1961, first realised in 1966 and remade in 2024), Yoko Ono. Photo: John Bigelow Taylor; © Yoko Ono

It’s difficult to imagine now, but in the 1960s art was not something you interacted with – not in a literal, physical way, as Ono frequently invites her audience to do. In an era when even the most radical artists were still hanging things on walls or putting things on plinths and asking people to look at them from a safe distance, the proposition expounded by the group of artists that would come to be known as ‘Fluxus’ – many of whom convened in Ono’s Chambers Street loft – was revolutionary. Their artistic concerns (Zen Buddhism, absurdism, the passing of time, indeterminacy, interaction, iterability) and the new media they used to explore them (film, performance, the assemblage, the event score) came naturally to Ono. As Lighting Piece demonstrates, to some extent they had always been her concerns.

On my second tour of the show one of the gallery attendants addresses me: ‘Would you like to experience what it’s like to be a soul?’ Before I know it, I’m taking my shoes off and clambering into a large cloth sack. Standing on a large white square on the floor, I am for a brief moment a sculpture: Bag Piece (1964). From the inside, the fabric is dark and soft but not totally opaque; I can see the world as if through gauze. The sound is slightly muffled. Everything seems a bit further away, somewhat abstracted. I wonder if souls always feel this self-conscious. ‘From my perspective,’ the attendant tells me after I’ve escaped, ‘you looked like something in Spirited Away.’ But beyond any spiritual associations, Bag Piece is also a work about the freedom that can come with concealing oneself. As so often in Ono’s work, she’s seeking ways to appear and disappear at the same time – or else to explore the gap between the two.

Ono would have to wait until 2015 for an official show at MoMA. By that time, her work had undergone one of the most dramatic re-evaluations in art history. In the few years prior, she had won a Grammy and a Golden Lion, exhibited her work at several major galleries and performed at Sydney Opera House in 2013. A video from that concert closes the current exhibition. She is no longer slouching beside a grand piano with a cigarette, but commanding the stage like a rock star. In black shades and designer clothes, she murmurs the words ‘I wish’, with digital echo effects making tidal waves of sound from the final sh, her singing building into a great soundscape of howls and rasps. The performance is taneously abrasive and curiously meditative, radical and slightly ridiculous, an explosive outburst and the highly controlled culmination of a lifetime’s development of a set of avant-garde vocal techniques that would influence everyone from Meredith Monk to The B-52s. For Ono, such apparent contradictions are par for the course.

Installation view of ‘Add Colour (Refugee boat)’ by Yoko Ono at MAXXI Foundation in 2016. Photo © Musacchio, Ianniello & Pasqualini

‘Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind’ is at Tate Modern, London, until 1 September.

From the April 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

How to give back looted objects