If the term ‘2 Tone’ is not immediately familiar to you, the music it’s associated with almost certainly will be. None more so perhaps than ‘Ghost Town’, released by The Specials 40 years ago this month: a lament for a Britain that, at the dawn of the 1980s, was haunted by recession, unemployment and inflation, and seemingly without any hope for the future. ‘Ghost Town’ might well rank as the bleakest song ever to have hit number one – and the more remarkable for being genuinely infectious too. A fixture on soundtracks and playlists ever since, it remains the acme of a genre that was – as the exhibition ‘2 Tone Lives and Legacies’ at the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum in Coventry demonstrates – a transformative moment in British pop culture.

A bundle of things all at once, 2 Tone was always about more than music. From a record label set up in Coventry in 1979 by the musician Jerry Dammers, it swiftly became a look, a political stance, and a banner to gather round; a movement with loyalties and aspirations way beyond the ska-inspired hits the label produced. Born in 1955 in India, to an Anglican dean, Dammers had come of age in a Coventry that was, for the time being, a boom town – redeveloped after the Second World War, thriving on industry, and growing on waves of migrants from Britain’s former colonies. By the late 1970s, the boom was over. The Midlands’ car factories stuttered and shut, jobs disappeared; crime went up, and racial tensions grew. As Britain was sliding into its Winter of Discontent, Margaret Thatcher was advocating ‘an end to immigration’ altogether, before the country should become ‘rather swamped by people with a different culture’.

For Dammers this was a moment of real fear and loathing. An animated film and triptych of drawings from his art school days, both on view in the exhibition, show Coventry’s streets as a Groszian nightmare of violence and civil decline. But Dammers had no fear of being swamped. A skinhead in the days before the style was fetishised by the far right, he was part of the wave of British kids inspired by Black youth culture: skins who had adopted the fashions, slang, and the music of Jamaica’s ‘rude boys’. While the major musical subculture of the generation – punk – remained a white affair, the original skinheads were proudly multiracial. Dammers’ inspiration was to bring these two scenes together, with a new style of music that mixed punk and reggae. When he realised just how uneasily punk’s literal speed-freak tendencies fit with reggae’s stoned slowness, he turned instead to its older, faster cousin: ska. The 2 Tone sound was born, incarnated in The Specials.

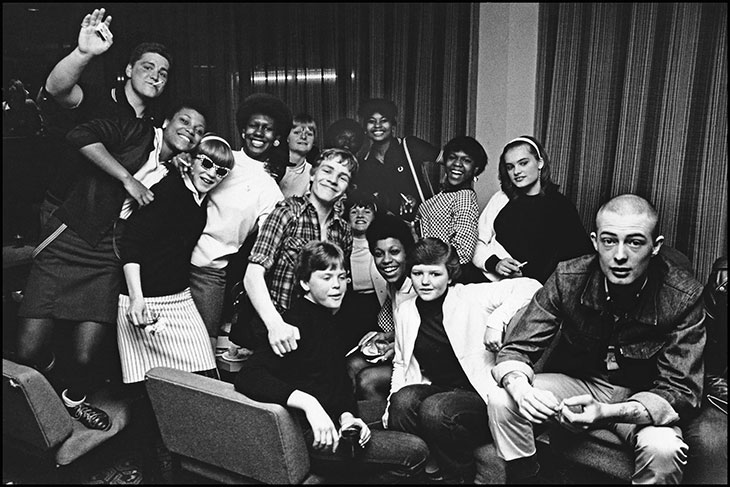

Photo: © Toni Tye

With his manic toothless grin, the young Dammers hardly presented the classic image of a Svengali, but what the exhibition makes clear is how focused he was on creating not just a group, but a whole scene. The Specials package was crafted with the maximal coherence. With members hailing from both the UK and the Caribbean, they were a picture of a Britain made richer in every sense by its former colonies. Dapper in rude-boy polos or tonic Mod suits, frontmen Terry Hall and Neville Staple were backed by a seven-man line-up that included veteran reggae trombonist Rico Rodriguez. When labels started to show interest, Dammers leveraged the group’s appeal into the deal that led to the creation of his own 2 Tone label, backed by the larger label Chrysalis, which he used as a launching pad for other groups. He then put his art-school training to use crafting a signature graphic identity. Everything 2 Tone featured the same black-and-white check and the same rude-boy mascot. Called ‘Walt Jabsco’ after the name on a bowling shirt owned by Dammers (a tattered artefact that has made its way into this show), the mascot was the perfect image of 2 Tone cool: insouciant in skinny suit, shades, and pork pie hat.

The image would have counted for little if the music had not lived up to it so fully. The Specials’ singles were a striking mixture of infectious good-time tunes and political paranoia precisely pitched for an audience who wanted to dance their way out of despondency. ‘Why must you record my phone calls?’ asks Hall on the debut single ‘Gangsters’. ‘Are you planning a bootleg LP?’ Reaching number six in the UK charts in May 1979, ‘Gangsters’ was the first in a run of hits that took on topics ranging from racial violence and unemployment to teen pregnancy without ever being anything less than danceable. The streak culminated in ‘Ghost Town’, but the song proved too much for the band itself. While its members continued to make music under various other guises, the original line-up split soon after its release, disagreeing over direction, exhausted by touring, and depressed by audience fights at their gigs.

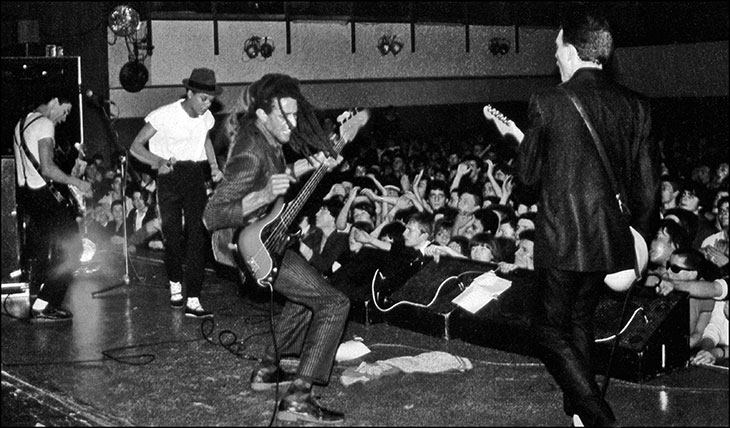

The Selecter gig. Photo: © Toni Tye

In the meantime, 2 Tone had taken Britain by storm, launching The Selector, The Beat, Bad Manners, and – biggest of all – Madness, whose ‘nutty nutty sound’ discarded overt politics in favour of invincible knees-up pop. In one episode of Top of the Pops in November 1979, no fewer than three 2 Tone groups were featured, marking the moment it went mainstream. Chaotic tours and high-energy gigs – immortalised in the documentary Dance Craze (1981) – left their mark on the bands’ members, but took the gospel far and wide. And for fans – captured here in a series of photos by Toni Tye and others – this was a religion, complete with a motley pantheon that ran from The Selector’s elegant Pauline Black through to Bad Manners’ bulldog frontman Buster Bloodvessel. This is, quite rightly, a fan-centric show: the curators have made space not just for band relics, but fan mementos too. A chequerboard dress handmade by a mum for her daughter and a black Harrington jacket larded with badges take pride of place in two spotlit vitrines.

Installation view of ‘2 Tone: Lives & Legacies’ at the Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, Coventry, 2021. Photo: © Garry Jones Photography

What had grown out of fear for community in Britain ended up a community all of its own – one that campaigned relentlessly for equality on and off the dance floor. While a song like Bad Manners’ ‘Ne Ne Na Na Na Na Nu Nu’ was never going to get mistaken for a protest anthem, other 2 Tone songs were at the forefront of raising consciousness of racism in Britain and abroad. Until Dammers and The Special AKA hit Top of the Pops in 1984 with ‘Free Nelson Mandela’, many of those watching hadn’t even heard of the African National Congress and its leader. The single made it to number nine in the charts. The term ‘legacy’ occasionally feels overblown in the context of pop, but here it does not. Without ever losing their sense of fun, 2 Tone groups and their fans knew this would be music that mattered; and it did.

‘2 Tone: Lives & Legacies’ is at the Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, Coventry, until 12 September.