From the July/August 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Back when she was still a struggling artist, before landing the commission to paint a portrait of former first lady Michelle Obama, Amy Sherald imagined her own major museum retrospective. She even dreamed up its name: ‘American Sublime’, a reference to the beauty and terror of her roots in the South. That vision has now manifested at the Whitney after travelling from the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. In September it will open at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., despite President Trump’s order for the removal of ‘divisive, race-centered ideology’ from the Smithsonian, of which the gallery is part.

The survey reveals the development of Sherald’s distinctive visual style across 42 oil paintings exalting the dignity of everyday Black folks. It also arrives at a grim chapter in US history when the progress made since the racial reckoning of 2020 is under broad federal assault, while in the art world, the boom in Black portraiture has reportedly gone bust. Against this backdrop of devaluation, Sherald’s bold, bright portraits register as defiant, optimistic and occasionally triumphant. In a recent interview, she described each painting as a ‘counterterrorist attack’.

Saint Woman (2015), Amy Sherald. Private collection. Photo: Joseph Hyde; courtesy the artist/Monique Meloche Gallery/Hauser & Wirth; © Amy Sherald

The Whitney’s iteration of ‘American Sublime’ begins with an artwork called Four Ways of Being (2025) that hangs on the facade of a building across the street from the museum, visible to those with a ticket and those without. It features four portraits of Black men from different generations posed in fashionable outfits like models from a catalogue, each of them set against a monochrome colour field that makes their clothing pop. Sherald’s style is immediately recognisable and has been praised on the one hand for capturing the interiority and individuality of her subjects and criticised on the other for a lack of emotional range. She has a chronic interest in how fashion communicates identity and a refined, coherent, method of composition. (A pleasure of this exhibition is noticing how the clothing of museum-goers interacts with the attire in the artworks.) We see Sherald’s repeating habits: the single subject, the steady gaze, the attention to posture, the pristine if idiosyncratic adornment, the spare flat plane, the retro look, the whimsical prop, the literary title, the talent for geometric design and, most prominent of all, the rendering of skin in grayscale, or grisaille.

Sherald uses grisaille to decentre race and highlight the humanity of her subjects. At least, this is what the wall texts tell us. But in my view, that narrative seems off. Black experience is anything but monolithic, yet upon first glance her body of work can feel just that. Trading the expression of warmth, variety and beauty reflected by brown skin while focusing so much on clothing risks a flattening effect. (Indeed, this was a common criticism of the Michelle Obama portrait when it was unveiled in 2018.)

Miss Everything (Unsurpressed Deliverance) (2014), Amy Sherald. Private Collection. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth; © the artist

The exhibition includes a short documentary called Everyday Icons (2023) produced by Art21 about Sherald’s practice. We see the black-and-white family photographs in the artist’s childhood home in Columbus, Georgia, and hear her talk about these self-stylised pictures and their emotional energy, especially in a portrait of her grandmother, Jewel, looking dapper in a tilted hat. The look is echoed in Miss Everything (Unsuppressed Deliverance) from 2013. It seems to me that Sherald uses grisaille to imitate the hauteur of Black studio portrait photography much as Renaissance painters used it to imitate sculpture.

Most of the portraits in the show are formatted exactly alike: three-quarter length, vertical, 137 by 109cm, hung at eye level, cut off by the knees. Notwithstanding the portraits of Michelle Obama and Breonna Taylor (the latter commissioned by Vanity Fair to eulogise the Kentucky medical worker shot in a botched police raid), none of the subjects are famous. In the aggregate, they take on a certain repetitiveness, like a deck of trading cards, or so many bugs frozen in amber.

I found myself most drawn to the paintings that subtly break Sherald’s mould, such as Saint Woman (2015), which shows a guarded woman in a turquoise dress against a yellow backdrop looking not at the viewer but off to the side. What is she looking at? There is a sense of mystery and uncharacteristic dynamism here. The pleats of her skirt appear ruffled by wind. What’s different about Alice is that she has the most incisive way of telling the truth (2017) is similarly arresting. A poised woman in a peach-coloured top and patterned skirt set against a sage green backdrop holds a 35mm camera at the level of her sternum. Her stare is inscrutable. Her manicured pointer finger rests on the shutter button, inviting the viewer to imagine the photograph she is about to take of them.

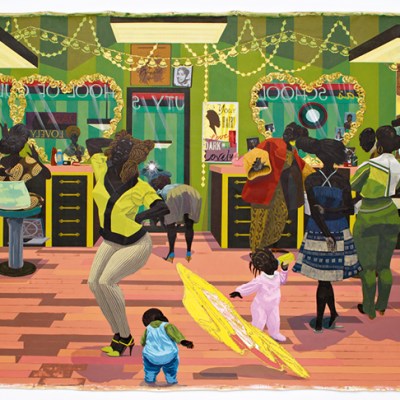

Kingdom (2022), Amy Sherald. The Broad, Los Angeles. Photo: Joseph Hyde; courtesy the artist/Hauser & Wirth; © Amy Sherald

More recent works, such as As American as Apple Pie (2021) attempt to subvert American archetypes, situating Black bodies in mid-century contexts typically associated with whiteness. Sherald’s corrective symbolism can sometimes tilt into preachiness, for example with American Grit (2024) which depicts a legless boxer in a ring bordered by red, white and blue ropes. A more subtle picture of freedom and defiance is the knockout Kingdom (2022). In this large-scale masterwork, a boy of about nine in a striped t-shirt under a denim jacket stands at the top of a shiny playground slide set against a blue sky, looking like a pioneer on a mountain peak. As the mother of Black boys, I found that this painting’s simple exuberance took my breath away.

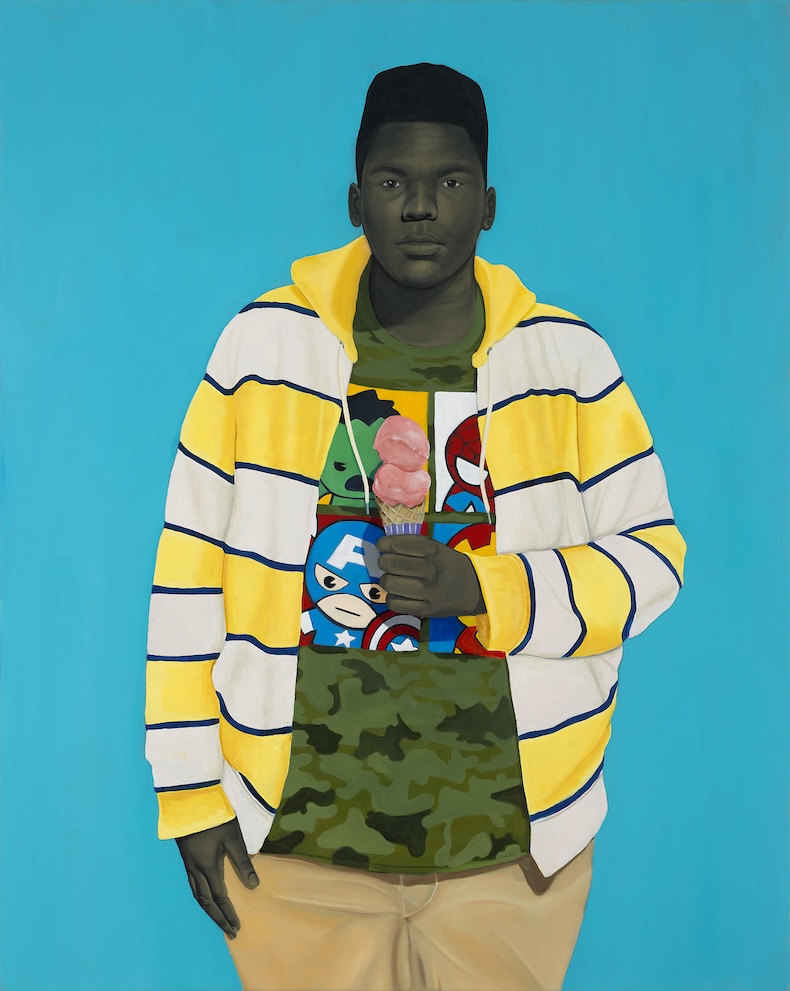

Sherald excels at painting the innocence, imagination, playfulness and potential of youth, liberated from the context of state-sanctioned violence. These may read as counterterrorist attacks, or anti-mugshots (since the Black body cannot be unpolitical), but the details here do more than humanise. How grateful I felt for the quirkiness of the flight goggles on the skinny teenager wearing a button-down shirt in The Boy with No Past (2014) and the ice-cream cone in the hand of the kid in Innocent You, Innocent Me (2016) looking so much in size, shape and sweetness like my eighth-grade son. Sublime, indeed.

Innocent You, Innocent Me (2016), Amy Sherald. Private collection. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth; © the artist

‘Amy Sherald: American Sublime’ is at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, until 10 August.

From the July/August 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.