The Love Potion. (1903; detail), Evelyn De Morgan. © 2025 De Morgan Foundation, Cannon Hall, Barnsley

‘Four things to see’ is sponsored by Bloomberg Connects, a free arts and culture platform that provides access to museums, galleries and cultural spaces around the world on demand. Explore now.

Each week we bring you four of the most interesting objects from the world’s museums, galleries and art institutions, hand-picked to mark significant moments in the calendar.

‘Drink Me!’ commands the tiny bottle that transforms Alice’s fortunes in Wonderland. In Lewis Carroll’s masterpiece, published 160 years ago this week, the contents of that miniature vessel launch Alice into an adventure in which scale – and reality itself – is always shifting. From ancient Egyptian perfume vessels to Venetian glass masterpieces, decanters of all kinds have proven not only useful as vessels but captivating as sculptural objects, often crafted with exquisite attention to detail.

Beyond their physical beauty, these objects serve as powerful symbols in art and literature: the communion chalice, Socrates’s hemlock cup, the alchemist’s transformative elixirs. Artists have employed bottles, glasses and potions as visual shorthand for intoxication, enlightenment, danger, healing and metamorphosis. In Jan Steen’s cautionary tavern scenes, Picasso’s absinthe glasses or René Magritte’s surreal wine bottles, these vessels represent transitions between states: sobriety to inebriation, illness to health, the ordinary to the extraordinary. This week we explore four works that celebrate or embody the role of drink in both fictional narratives and social settings.

Kayserzinn drinking set (c. 1905), Hugo Leven

Denver Art Museum

A pewter decanter in the shape of an auk, its spout resembling a beak, stands at the head of a gaggle of pewter cups. It was designed by the German maker Hugo Leven, who trained in Düsseldorf and made jewellery and tableware in an art nouveau style; most of his work is now considered lost. With their thin, curving handles and shapely, elegant bodies, Leven’s creations remind us that functional objects can be full of personality; the Kayserzinn drinking set is a prime example. Click here to find out more on Bloomberg Connects.

Drink Me (1870s), John Tenniel, made by York and Son with permission of MacMillan and Co

National Media Museum, Bradford

Alice contemplates a mysterious bottle in this hand-painted glass slide, originally part of a 42-piece set created for ‘magic lantern’ entertainment during the Victorian era. Tenniel’s illustration, authorised by and produced in collaboration with Carroll, anticipates Alice’s transformation and demonstrates Tenniel’s gift for subtle character detail – he was also a remarkable satirist and caricaturist. Click here to find out more.

The Drunken Couple (c. 1855–65), Jan Steen

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

A pewter jug and a barrel are prominent in the foreground of this cautionary scene, in which an inebriated couple are blissfully unaware of thieves entering behind them. Steen’s meticulous rendering of the drinking vessels makes them seem like mute witnesses to the unfolding misfortune. The painting is an example of the kind of moral commentary often found in art of the Dutch ‘Golden Age’; here it’s underscored by the owl portrait on the wall – a symbol of blindness and folly. Click here to read more.

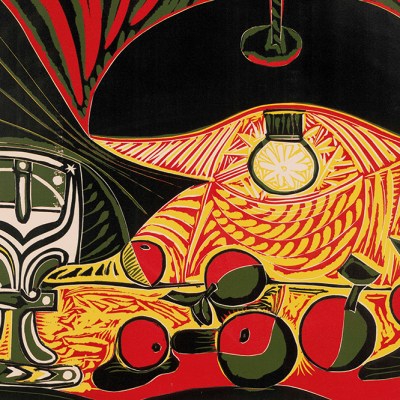

The Love Potion (1903), Evelyn De Morgan

De Morgan Collection, Barnsley

A golden-robed figure prepares an alchemical mixture while distant lovers appear through a window. Despite incorporating traditional witch-related iconography such as the black cat, De Morgan subverts expectations by presenting a learned scholar surrounded by philosophical texts. In alchemical colour symbolism, yellow signifies spiritual enlightenment; its prominence in the painting is indicative of De Morgan’s spiritualist belief in the progression of the soul towards transcendence. Click here to discover more.

‘Four things to see’ is sponsored by Bloomberg Connects, a free arts and culture platform that provides access to museums, galleries and cultural spaces around the world on demand. Explore now.