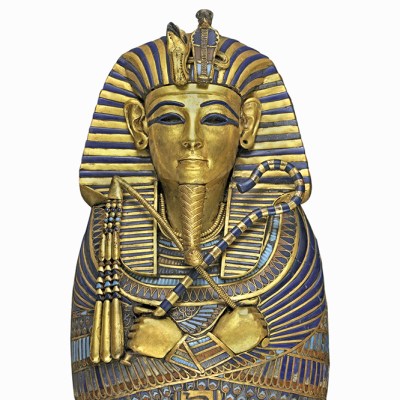

On 27 July, a London auction house will attempt to sell an exquisite 3,300-year-old Egyptian painted ivory grasshopper. Under 9cm long and estimated at £300,000–£500,000, it spent more than 50 years on display in a major museum and passed through the hands of renowned archaeologists, dealers, collectors and royalty. Some experts also believe that it comes from the tomb of Tutankhamun.

The Guennol Grasshopper, as it is known, takes its name from the collection formed from the 1940s onwards by Alastair Bradley Martin, heir to a Pittsburgh steel fortune (‘gwennol’ is Welsh for martin). He purchased ahead of the curve and exhibited and published his collections astutely. ‘Guennol’ objects have long been sought after by younger collectors anxious to establish a name for themselves. The Guennol Lioness, a 5,000-year-old Iranian statuette, 9cm high, broke all records for a sculpture when it sold for $57m in 2007. A little before this, Sheikh Saud al-Thani, a senior member of the Qatari Royal family, bought the grasshopper for a comparatively modest $1.2 million.

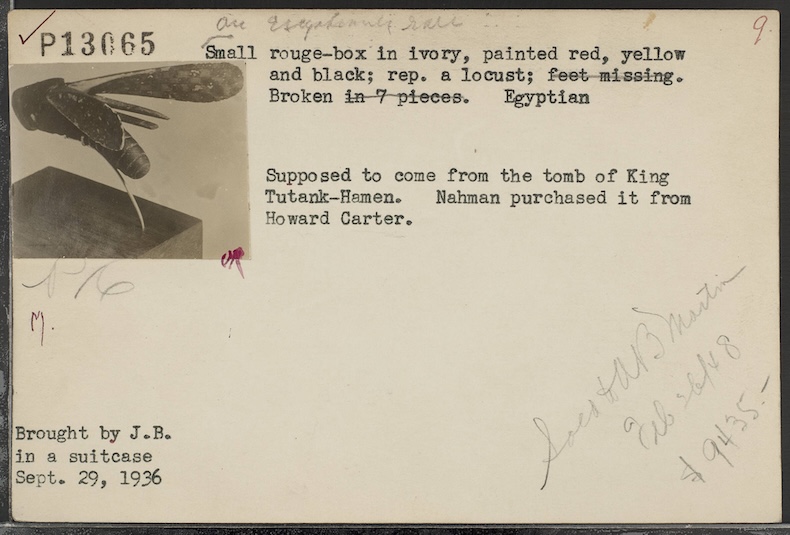

Martin himself paid just under $10,000 in 1948 (approximately £100,000 today) for the grasshopper from the estate of Joseph Brummer, a New York dealer. Brummer’s meticulous catalogue cards, now preserved in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, state that he had acquired it in 1936 from Egyptian dealer Maurice Nahman, who bought it from Howard Carter.

Carter’s pilfering of small, beautiful, valuable and mostly uninscribed objects from the tomb of Tutankhamun – a category of objects which belonged entirely to the Egyptian people, and were not his to take – has long been an open secret in Egyptology. During his lifetime Carter discreetly touted around and sold a few objects said to come from the tomb, such as the Guennol Grasshopper, and after his death in 1939 his executors discovered a hoard of objects in his Kensington flat which seemingly did: either they were inscribed with Tutankhamun’s name or were made in the refined artistic style of his reign, were of royal quality and were so well preserved they must have been buried in the tomb. Carter’s executor Harry Burton, who worked for the Met, returned objects with Tutankhamun’s name to the Egyptian Embassy in London and sold the rest. Private collectors and museums including the Met purchased objects, which Carter’s own personal notes (now missing) baldly stated came from Tutankhamun’s tomb. These objects were sold with a suggestive history and at prices to match their illustrious findspot. Museum curators and directors had plausible deniability but enjoyed bragging about their haul to colleagues and friends: Alastair Bradley Martin’s curator blandly catalogued his grasshopper as ‘probably from Western Thebes’ but Martin himself couldn’t resist listing ‘the Egyptian grasshopper from the cursed tomb of Tut’ among his favourite objects. The cartoonist Charles Addams sketched an amiable looking Martin buying the grasshopper from a ghoulish dealer who assures him, ‘Now this one is supposed to have a curse on it.’

Thomas Hoving, the maverick director of the Met from 1967–77, blew the whistle on his museum’s Tut holdings and the Guennol grasshopper in his book Tutankhamun: The Untold Story (1978), based on documentation in the Met’s own archives and conversations with senior curators who knew Carter and Burton. The Met returned some of the contested objects in 2010. Several of the objects Hoving identified as looted from Tut’s tomb remain on view at the museum, however – Egyptologists joke that the pretty ones got to stay behind – but the tide seems to have turned against the display of unquestionably looted objects.

In this atmosphere, how will the Guennol Grasshopper fare in a public sale? Sheikh Saud al-Thani, who died in 2014, was renowned for his ‘eye’ for a striking object and a willingness to overlook complicated provenances. In 2005 he was held under house arrest accused of misappropriation of public funds to buy for his private collection; he had also bought quantities of antiquities from the disgraced dealer Robin Symes. His heirs have been attempting to dispose of his vast collections since his death, often receiving only a fraction of the price he paid at the time. Both Christie’s and Sotheby’s were approached to sell the grasshopper but ultimately declined; it is now on offer with Apollo Auctions, a relative newcomer to the trade in ancient relics – and no relation to this magazine – in Fine Ancient Art – The Prince Collection: The Legend of Tutankhamun. This writer has handled the grasshopper in London. Although its fragile wings have been damaged, it is still a mesmerising object, made to delight a sophisticated ancient audience and equally sure to please a modern owner.

When this magazine asked if the object had been looted from the tomb of Tutankhamun, Apollo Auctions stated that ‘The connection to Tutankhamun’s tomb is a recent scholarly hypothesis and not an established fact, and as such does not constitute legal or historical proof.’ It added, ‘There is no excavation photograph of this item in the tomb, Carter never listed it in the inventory, [and] no definitive documentation proving it came from KV62’. Apollo Auctions said it had carried out ‘extensive due diligence before listing the piece for auction and received a certificate of clearance confirming that the item had not been stolen or looted. In the printed catalogue for the auction, page 8 says that the grasshopper is ‘believed to be among the “known and potential strays” from the tomb of Tutankhamun, and once part of the collection of the late Howard Carter’.

Institutions have been slow to react to the proposed sale of the grasshopper. The Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities usually protests about auctions of ancient objects, whatever their history, but has remained silent so far; the British Museum, which liaises with Scotland Yard over objects with disputed title, has said nothing, even though the grasshopper has been linked to Tutankhamun’s tomb from its first appearance on the art market nearly 90 years ago. One can only wonder at such reticence.