This review of Monsieur Ozenfant’s Academy by Charles Darwent is from the September 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Here is a handy piece of pub quiz trivia: who was the first painter ever to go on television? It was December 1937 when the BBC gathered a sculptor, a wood engraver and a painter together for a programme modestly named Three Artists and a Bowl of Fruit. They could each arrange and represent their bowl of fruit in any way they liked. The painter takes up the story:

I prepare a still life of ten apples, eleven oranges and a pineapple. To show that it is not the subject and object that matter most in art, but forms and their effects, I first make a ‘realist’ conception of this still life on a blackboard, then a cubist one, then I turn the still life into a landscape where the fruit become rocks and the pineapple a palm tree – the purist mode.

It sounds like a star turn, serious and entertaining at once and ‘[t]he camera unexpectedly loved him’, as Charles Darwent reports in his fascinating new book. But the broadcasting experiment was never repeated, with the impending war taking the painter away from London to New York and limiting the BBC’s capacity for such adventurous programming for years to come. No footage of the programme survives. If it was ever recorded, the recording has not been preserved.

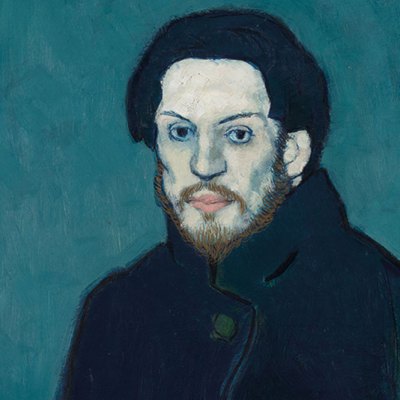

It is a characteristic moment in Darwent’s study, for the painter is the now little known Amédée Ozenfant and many aspects of his life and work have had to be guessed at by his biographer, or pieced together from fugitive traces. ‘As so often in Ozenfant historiography, there is an annoying evidential gap,’ Darwent writes, when he tries to reconstruct Ozenfant’s unrealised plan for a floating exhibition that would take French culture around the world via the high seas in 1938. ‘Other than this, all is scraps and ghosts,’ he writes, in assessing the influence of the art school that Ozenfant ran in London from 1936 to 1939. This is a study of a disappearance, of a figure who once seemed eminent but has since been almost totally forgotten and, as such, it has a slightly melancholy air.

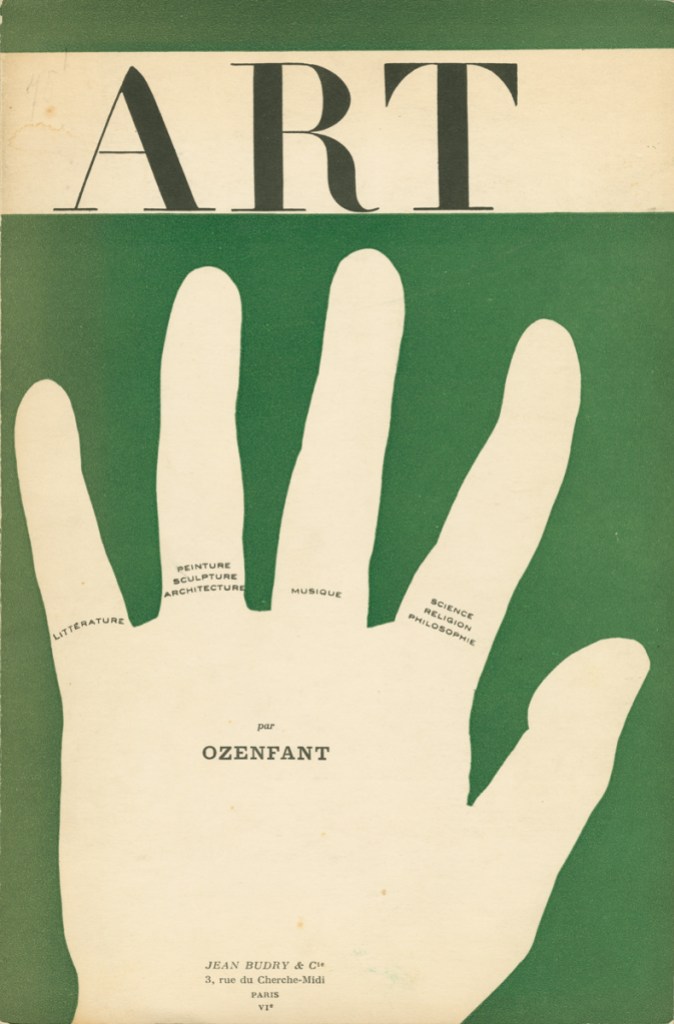

When Ozenfant begins to come into his own in the late 1910s, great things seem possible. He is a friend and mentor – possibly a lover, it has been suggested – to a younger man, Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, and he encourages him to adopt a new pseudonym, stately and classical sounding: Le Corbusier. Together the pair write a series of essays expounding the doctrine of ‘Purism’ that will be in tune with modernity and the machine age but will install ‘a new sense of restraint that will rouse the country from its troubled sleep’, much needed after the chaos of the First World War. It will be an art in search of ‘object types’, shapes such as a guitar or a carafe that have evolved over centuries into pure, economical forms that can be observed and mass-reproduced in standardised processes.

Ozenfant’s ideal would survive the end of his friendship with Le Corbusier, and it would be a powerful influence on his teaching practice. At the Académie Moderne in Paris and then at the Ozenfant Academy in London, he would put his students through an exceptionally rigorous programme of instruction designed to refine their feeling for pure forms. The students would be ordered to draw from life using only the hardest 9H pencils, on a paper size known as ‘double elephant’ – sheets so big that they could practically draw their life models life-size. Shading was impossible with such hard pencils; it was all disegno and no colore, with the emphasis on the slow, painstaking process of getting the outline right.

Unsurprisingly, it didn’t please all of Ozenfant’s students. The evidence for the importance of Ozenfant’s London academy gets stretched a little bit thin by Darwent’s meticulous survey, since it may have admitted as few as 50 students over the three years it was open, and only one of them, Leonora Carrington, found lasting repute in her lifetime. The irony of Ozenfant’s teaching is that though he conceived of the classicism of Purism in opposition to the libidinal disorder and unconscious drives of Surrealism, he appears to have turned many of his students, such as Carrington and Stella Snead, into Surrealists. As is ever the case in teaching, the lessons his students took from him were not exactly the ones he had offered.

That’s as it should be – but what of Ozenfant as an artist? Much of the story of Darwent’s books is taken up with the creation of his largest painting, VIE, which he started in 1931 and finished in 1938. The capitalisation of the title is Ozenfant’s own and it attests to the grandiosity of his ambitions in this work, to represent what he called ‘the unfolding of Existence’ through ‘[a] jumble of lives obeying at the same moment the same essential forces, symbolised by the eternal analogies: morning-birth-youth, noon-strong age, evening-old age – and death, etc.’ It’s an admirable idea and the painting looks startling in its reproduction here. But to spend the years of gathering political and social darkness in Europe working on a huge canvas animated by a naively optimistic vision of universal brotherhood seems comically out of tune with the age. VIE was acquired by the French government but was last shown in a small exhibition in Cannes in 1995.

In the end, Ozenfant remains a minor but likeable figure, probably more important as a theorist than a teacher or a painter, whose claim to attention must have rested in large part on his personal charisma and presence. Darwent reproduces in an appendix his own translation of Ozenfant’s diary from his London years, which is a fascinating document of a cultural mover and shaker in the late 1930s with a deft feeling for Anglo-French relations and the possibilities of art as national propaganda. And attending to minor figures is always worthwhile, not least because it reminds us how much chance and contingency are involved in determining what is of historical importance. Ozenfant’s work is unlikely to make a comeback at this late stage, but Charles Darwent has done a riveting job of making him visible in his oblivion.

Monsieur Ozenfant’s Academy by Charles Darwent is published by Art Publishing, Inc.

From the September 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.