From the September 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

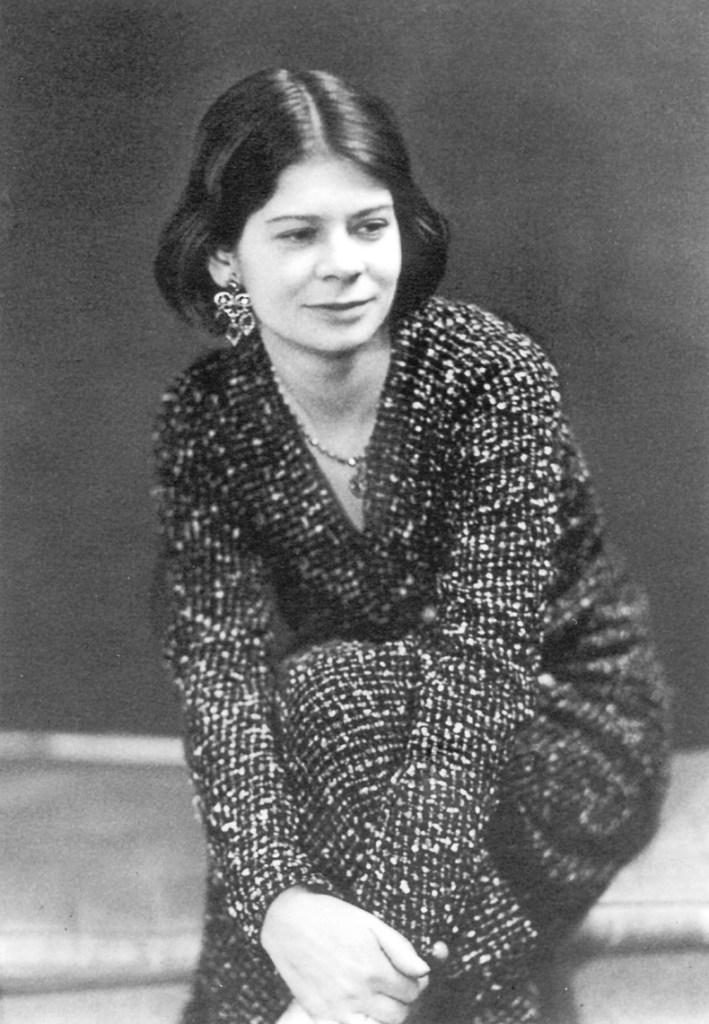

In 1966 the collector Margaret Gardiner (1904–2005) wrote to her close friend, the painter Ben Nicholson, that she was ‘haunted by this horrible war’. Gardiner was referring to her campaign to highlight American policy in Vietnam, which had begun in earnest a year earlier, and to protest at what she regarded as the British government’s complicity. Some 60 years later, her particular way with dissent seems worth revisiting as new wars and new protests emerge in a world of polarisation and intolerance.

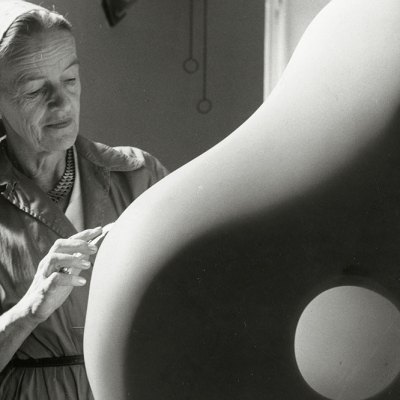

Gardiner set out her extraordinarily varied and long life in a small literary masterpiece, A Scatter of Memories (1988), in a short lyrical memoir of Barbara Hepworth (1982) and in an account of her undergraduate friendship with the anthropologist Bernard Deacon, Footprints on Malekula (1984). She had an abiding commitment to protest, saying, ‘I think it was always natural for me to join in anti-war activities.’ Going against the grain and an absence of conventional patriotism was built into the psyche of both Margaret and her older brother Rolf. I have been writing their joint lives as a way of examining political and artistic difference in the 20th century, guided by their friendships – from D.H. Lawrence, to the occultist Robert King, to the German puppeteer Harro Siegel, to W.H. Auden and the Communist crystallographer J.D. Bernal – and by their commitment to causes as diverse as reforestation and organic farming (Rolf) to independence for Nyasaland, now Malawi (Margaret).

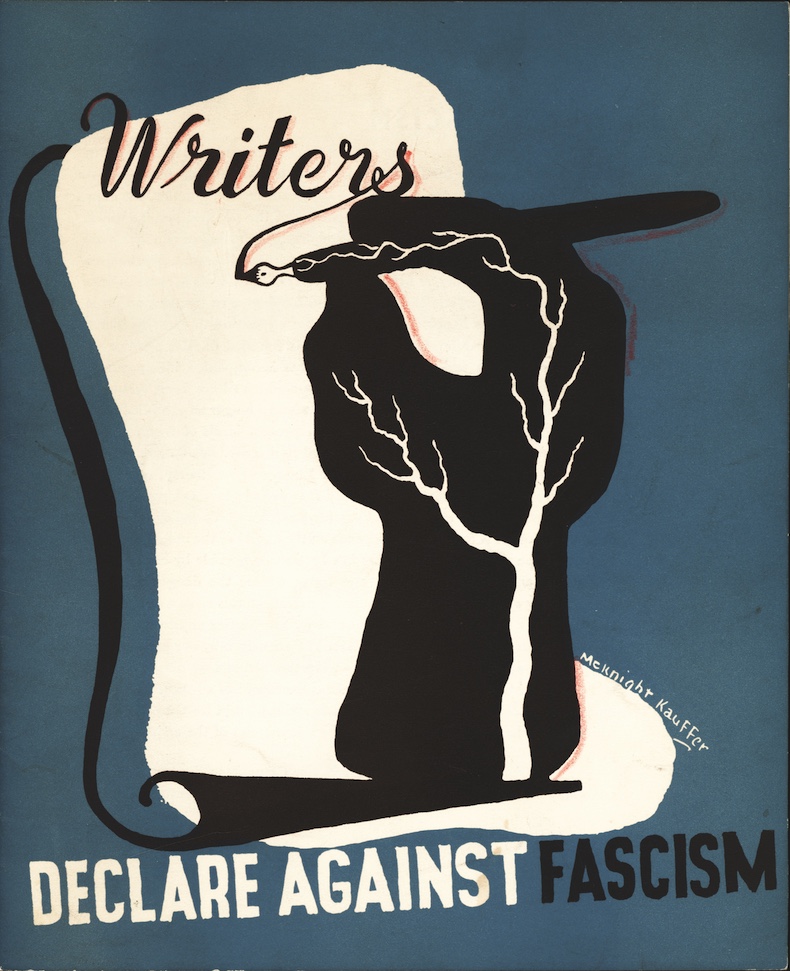

Perhaps their radicalism and disregard for convention was learnt from their father, the distinguished Egyptologist Sir Alan Gardiner, who had passionately opposed the First World War, attracting much criticism. Rolf was involved with the German youth movement in the 1920s, becoming an anti-modern modern who was drawn to the occult, to folk dance and song, good husbandry and the repopulation of the land – a coalition of enthusiasms that led him in 1933 to support National Socialism. Gardiner became politicised after 1930 mostly through her friendship with Hepworth, who, she recalled, was ‘always concerned with politics and social problems’. The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in July 1936 was a turning point and by then Gardiner had met Bernal, with whom she had her son Martin in 1937. With Bernal she turned to activism, becoming in 1936 the Honorary Secretary of an organisation called For Intellectual Liberty, the purpose of which was to fight fascism. Encouraged by Hepworth, she commissioned László Moholy-Nagy to design a dramatic jacket to wrap round the group’s brochures while Edward McKnight Kauffer designed the cover of the pamphlet Writers Declare Against Fascism.

Today Gardiner is best known as a collector of modern British abstract art and in particular as the patron of Hepworth and Nicholson from the early 1930s onwards. She gave the bulk of her collection to the Orkney Islands and since July 1979 it has been housed at the Pier Arts Centre, Stromness, in a former warehouse overlooking the harbour. It includes some of Hepworth’s loveliest early work – Figure in Sycamore (1931), her alabaster Two Heads (1932) and the alabaster Large and Small Form of 1934 – along with fine paintings and reliefs by Ben Nicholson, a Naum Gabo Perspex and nylon monofilament construction of 1942–43 (one of four originally owned by Gardiner) and a range of exceptional work by younger artists, many with links to St Ives. To create what amounted to a new public art gallery demanded all Gardiner’s determination and charm, marked by her ability to find institutional allies – from the Scottish Arts Council to Thomson Scottish Petroleum. And Gardiner’s ongoing patronage of advanced art made the notably aesthetic dimension to her forms of political protest almost inevitable.

Gardiner had wanted to be an artist herself since the 1930s and her continuing espousal of a range of causes after the Second World War may have been a compensation for what she perceived as creative failure. She went on the first Aldermaston March in 1958 and subsequently threw herself into protest. But, with a measure of arrogance, she told Nicholson that the demonstrations staged by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and the Committee of 100 had ‘alienated public opinion’ and had made them appear ‘eccentric and disreputable’. Gardiner decided that modern advertising techniques would best convey the urgency of nuclear disarmament to the general public, placing advertisements asking for volunteers in World’s Press News and Advertiser’s Weekly. Marcus Brumwell – a friend of Hepworth and likewise a patron of modern art – and other advertising men agreed to help, using the same techniques employed to sell cars or biscuits to push for nuclear disarmament. A trial scheme was launched in Nottingham in mid September 1962. Gardiner told Hepworth proudly that she had raised £6,400, ‘dropping any personal life or writing – and seeing endless people and writing endless letters till I got wound up so tight that I thought my strings would snap’. Plans to show three-metre-high posters of an anxious mother with a pram and the rubric ‘Has anyone asked this woman how long she wants to live’ and another poster of a skeleton mother pushing a pram with a skeleton baby in front of a mushroom cloud under the slogan ‘Say no’ were scrapped as unlikely to be accepted for display. Instead, a series of ‘Say No’ teasers were followed by two posters – a group of playing children with ‘for their sake SAY NO to nuclear bombs’ and another of a toddler with a similar message. These were displayed at 55 sites in Nottingham between September and December 1962. The tour de force, planned for the final Saturday of the campaign, was the placing of a six-metre replica atomic bomb made of wood in the market square, with passers-by encouraged to pledge ‘no’ by hammering a nail into the ‘bomb’. These arrangements were vetoed by Nottingham council. Instead, the ‘bomb’, painted with the slogan ‘The only bomb the Council banned’, was mounted on a lorry and driven round Nottingham, a setback seen by Gardiner as a happily unexpected publicity coup.

In A Scatter of Memories Gardiner recalled visiting the etcher W.S. Hayter in Paris in 1965: ‘He said to me, “Oh, this might interest you,” and handed me a copy of the New York Times in which there was an advertisement signed by American artists against the war in Vietnam.’ Two years into the presidency of Lyndon B. Johnson the conflict had escalated, with sustained bombing missions and some 185,000 American troops in Vietnam by the end of 1965. ‘Bill said, “I wish they’d do something like that in England.”’ Hayter was referring to two full-page advertisements that had appeared in the New York Times in April and June 1965, organised by the New York-based Artists and Writers Protest (AWP). Both asked the cultural community to END YOUR SILENCE regarding the war in Vietnam. Both were graphically eye catching. The first, published on Easter Sunday, had signatures ranged centre with different line lengths that wandered down the page like a concrete poem. The second, which appeared under the same heading on 27 June, was endorsed by the Los Angeles-based Artists’ Protest Committee, a formidable anti-war organisation with 200 members. Again, the design was striking, elegantly typeset in columns. The text was longer, referring to the protests of French intellectuals against ‘la sale guerre’ in Algeria in the 1950s. And it was broader in scope. There was the ‘din of bombs falling on Vietnam’ but also recent American interventions in the Dominican Republic.

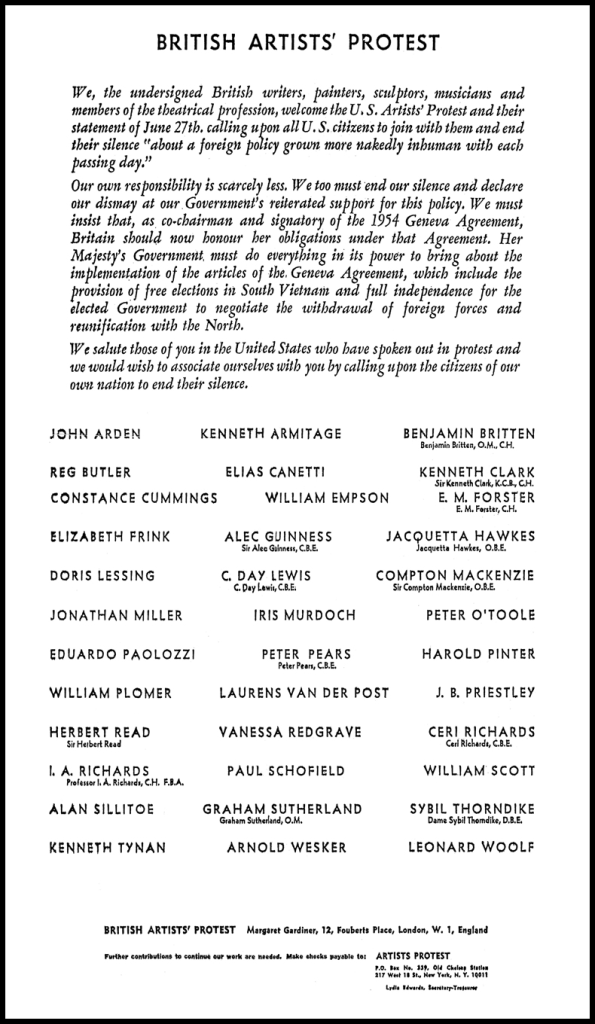

Inspired, Gardiner raised money and gathered signatures for a full-page advertisement in the New York Times appearing on 1 August 1965. Under the rubric ‘British Artists’ Protest’ it expressed dismay at the British government’s support for American policies, asking Britain to implement the 1954 Geneva Agreement and calling for elections in South Vietnam. If the figures from the advertising world who helped orchestrate the Nottingham project had wished to remain anonymous, a willingness to stand and be counted was now central to Gardiner’s purpose. Thirty-six British writers, painters, sculptors, musicians and theatre people signed, including the sculptors Kenneth Armitage, Reg Butler, Elisabeth Frink and Eduardo Paolozzi, the painters Ceri Richards and Graham Sutherland, the writers E.M. Forster, Doris Lessing and Iris Murdoch, and the playwrights Harold Pinter and Arnold Wesker. But non-signers were of interest also. Hepworth did not sign, feeling some mention should be made of the UN, while the poet Stephen Spender was characteristically strategically cautious.

The ‘British Artists’ Protest’ was followed by a half-page advertisement in the New York Times on 12 December 1965 signed by 46 cultural figures across Western Europe. It was an impressive list that included the philosophers Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre, the writers Heinrich Böll, Marguerite Duras, Max Frisch and Günter Grass, the artists Max Bill, Max Ernst, André Masson and Ben Nicholson, and the composers Karlheinz Stockhausen and Michael Tippett. The novelist Nancy Mitford signed from Paris and Gardiner got a positive response from Hepworth who wrote sympathetically, ‘I well appreciate that it takes 330 letters to get 30 signatures.’ But Jean Arp and Arthur Koestler announced themselves as non-signers of political manifestoes. Jean Dubuffet (who wrote a long thoughtful letter) and the architect Gio Ponti felt they were not well-enough informed. Kingsley Amis pointed out that he wholeheartedly supported American policies.

From Frankfurt the cultural theorist Theodor Adorno acknowledged Gardiner’s serious intentions but also refused: ‘The only reason for this is that the whole Vietnamese situation seems so hopelessly muddled and complex to me that I cannot protest against the atrocities of one side without branding the equally bad ones of the other … Obviously, I am not at all suitable for signing manifestos; what someone like me can contribute against inhumanity, for example, must be done in his own work.’ The singer and conductor Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau similarly refused, believing that only through his work could he contribute to world peace. The writer Uwe Johnson disliked the wording of Gardiner’s text. The poet and essayist Hans Magnus Enzensberger signed, although he found Gardiner’s text with its talk of ‘death, mutilation and misery’ and the prospect of a third world war ‘too wild’. In Paris, Gardiner was rebuked by the artist Serge Poliakoff: art came before politics. The writer Elizabeth Bowen wrote a long refusal, deploring the war but also the validity of well-known artists and writers signing: ‘Why should their own names carry more weight than that of the ordinary citizen?’

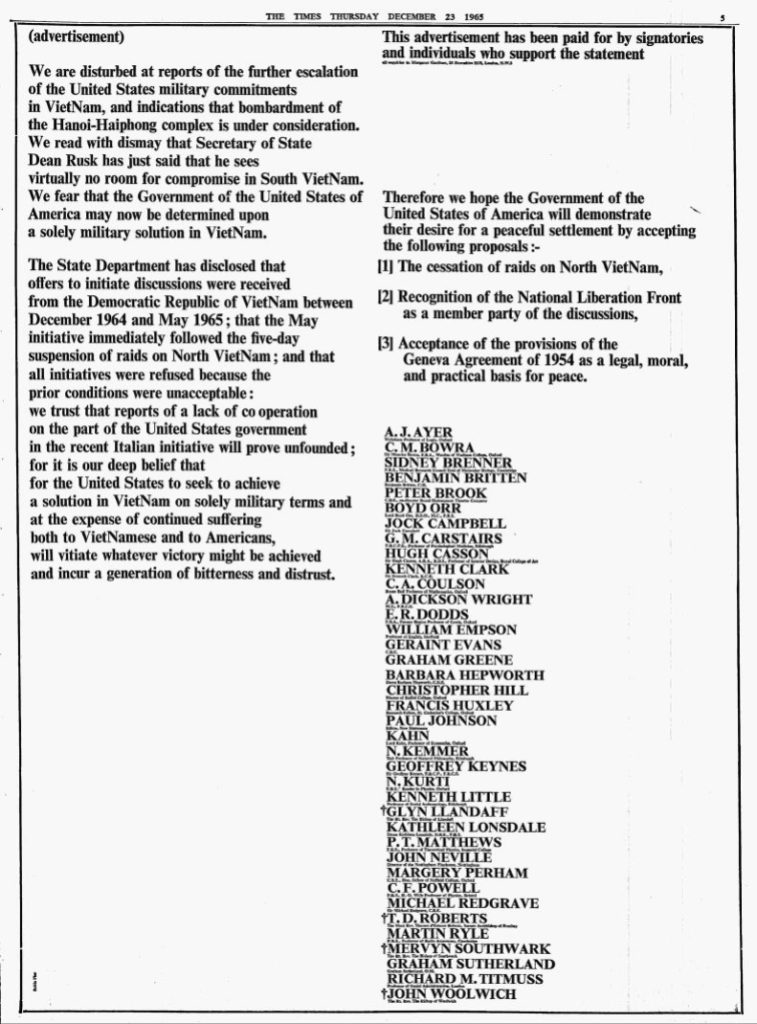

Bowen notwithstanding, Gardiner felt that only famous names – preferably of artists and intellectuals of all kinds – carried suitable heft. Her third advertisement in the London Times on 23 December 1965 deplored ‘reports of further escalation of the United States military commitments in Vietnam’. Designed by the radical typographer Robin Fior at the suggestion of Vanessa Redgrave, it was visually dramatic. As Fior recalled, the advertisement ‘was set in two columns of Times Bold with signatories’ names in Bold Titling, while their titles or honours were set in 6 points below the name, with perhaps 2 points before the name following. There was a crucial horizontal alignment between the columns. All this was carefully drawn in ink on medium-weight tracing paper and duly delivered to the head of the composing room, who received it without much enthusiasm […] But it was printed two points out of alignment.’ Unaligned or not, the effect was powerful, as was the array of names with a pronounced emphasis on academics and the clergy. Hepworth and Graham Sutherland were the only two visual artists.

On 25 April 1966 the Times carried a fourth advertisement, ‘Labour voters & Vietnam’, designed by Fior using the same typefaces, this time with correct columnar alignments. Signatories had to have voted Labour in Wilson’s sweeping victory the previous month. Gardiner’s text argued that Wilson’s electoral success was not, as Lyndon B. Johnson appeared to believe, an endorsement of Wilson’s support for US interventions in Vietnam. There were plenty of refusals but it was nonetheless a good list, which included the artists Patrick Heron, David Hockney, John Piper and Joe Tilson. Gardiner told Nicholson that it provoked many letters, mostly of support.

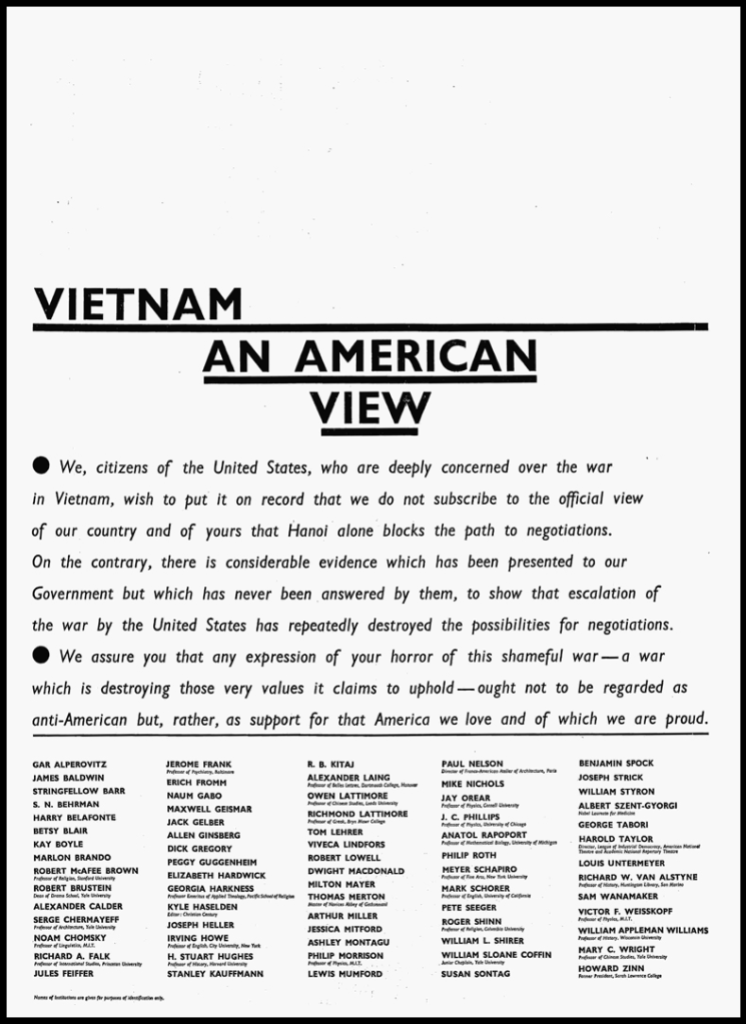

More advertisements followed, including one that Gardiner aided but did not initiate. Appearing in the Times on 24 January 1967, ‘Britain and Vietnam’ urged the British government to withdraw support for US policy and was signed by 1,500 academics. Taking up six impressive columns, it looked like a war memorial translated into print. Gardiner’s fifth advertisement, ‘Vietnam: An American View’, which appeared in the Times on 2 June 1967, was signed by 71 North Americans including James Baldwin, Alexander Calder, Serge Chermayeff, Noam Chomsky, Naum Gabo, Allen Ginsberg, R.B. Kitaj, Robert Lowell, Thomas Merton, Jessica Mitford, Lewis Mumford, Susan Sontag and Benjamin Spock. It made the point that distinguished Americans opposed the Vietnam War and provoked plenty of refusals to sign on grounds of patriotism. The artist Robert Motherwell declined, wanting condemnation of the North Vietnamese as well as the American government, a point made by many of Gardiner’s refusers. On 5 December 1967 the Times ran Gardiner’s Britain and American Draft Protests. This voiced admiration for young Americans who refused to fight and was signed by 12 well-known British figures – including John Le Carré, Peter Ustinov and Raymond Williams. Gardiner was still collecting signatures in 1972: ‘We, the undersigned, like millions of others, felt indescribable relief at the news of the Accord agreed … between the Governments of the United States and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.’ That the Accord was now being questioned by the American government was ‘unspeakable conduct’. The letter was to be published in the United States via the Quaker Peace Division and, as Gardiner explained to the scientist Francis Crick, ‘In this country I am only approaching Nobel Laureates and members of the Order of Merit for signature.’ ‘Sorry, I don’t sign political things,’ was the terse reply. His was not the only example of fatigue with Gardiner’s continued demand for signatures.

Gardiner also saw the publicity value in creating drama on the streets of London. If she had little time for existing peace organisations, she was impressed by the International Confederation for Disarmament and Peace (ICDP) and worked alongside the charismatic activist Peggy Duff. She became its treasurer and supported it with her own money, telling Nicholson in 1969 that ‘it is far and away the best peace organisation at present – partly because it is international and can be effective in so many places and partly because we are personally close to the two Vietnamese delegations in Paris, see them frequently and are able to consult with them as to the most helpful things that we can do.’ She was almost certainly behind the powerfully designed and unsparing ICDP leaflet headed ‘14 Bombing Days to Christmas’, published on 10 December 1966 to coincide with a vigil outside St Martin-in-the-Fields and carol singing on the steps of St Paul’s Cathedral.

Gardiner also commissioned a work from the challenging composer Alexander Goehr. He turned out a tuneful King Herod’s Carol with words by Erich Fried and Gardiner in which Herod’s Massacre of the Innocents segued to the death of Vietnamese babies: ‘Kill them all to keep the free world free.’ Gardiner also wrote a version of ‘O Tannenbaum’ beginning ‘O Annenberg’, referring to the US Ambassador in London, which some 50 protestors sang outside the embassy. In a more dramatic event, on Boxing Day 1971, Gardiner asked friends to come to the US embassy bringing boxes labelled ‘Bombs for Babies’, wrapped in Christmas paper. Press photos show the ‘presents’ deposited outside the embassy and flanked by four children in Santa Claus costumes and skull masks.

Walter Annenberg’s gift of £40,000 to refurbish Chequers, the Prime Minister’s country house, inspired another protest at the devastation of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. The painters David Hockney and Patrick Procktor, dressed as top-hatted bankers, were photographed outside the US embassy on 3 January 1972 presenting a ‘cheque’ for the same sum to be used to ‘Fumigate the White House’. Uncurated protest, however, found little favour with Gardiner. Robin Fior’s first wife, Jane, recalls asking to join one of these carefully orchestrated protests. Gardiner’s response was counter-intuitive but telling: ‘It’s a private demonstration.’

Gardiner had begun campaigning against the Vietnam War in August 1965. She was still involved when the war ended, marked by the fall of Saigon in April 1975, not least by funding the young poet James Fenton’s second visit to Cambodia and Vietnam in 1974–75. She was undoubtedly buoyed by a good measure of privilege. And she got some things wrong. Deferring to her son Martin, she was annoyed by Fenton’s prescient anti-Khmer Rouge article written for the New Statesman in April 1975. But her imaginative and visually striking proselytising deserves our attention and admiration.

From the September 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.