From the September 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In 1925, for the Exposition des Arts Décoratifs, the couturier Paul Poiret (1879–1944) moored three barges on the Seine near the Pont Alexandre III. Named Amours (presenting interior design work), Orgues (for fashion collections) and Délices (for perfumes and a restaurant), each represented a different part of the designer’s over-extended business empire. Looking back on the venture in the memoir he published five years later, Poiret considered it a colossal failure. Not only had he paid for everything himself, but the whole exhibition was the wrong kind of event for Parisians who could afford what he was promoting: ‘At the most, in the evening between 9 and 11, one saw a flood tide of concierges and workpeople who liked lights, a crowd, and noise.’

The riverside extravaganza sank Poiret’s already faltering fortunes. The previous year, he had sold his fashion house, Maison Paul Poiret, to a finance group that allowed him to stay on as artistic director and had bought the rights to his name. In late 1925 he floated the interior design and perfume businesses he had held on to as public companies and sold 110 pieces from his art collection, including works by close friends and collaborators such as André Derain, Kees van Dongen and Raoul Dufy. Worse was to come: in 1928 he was forced out of Maison Paul Poiret altogether and Denise, his wife of 23 years and the most important inspiration and model for his designs, divorced him. A year later, he was declared bankrupt.

There’s more than a touch of irony then about the Musée des Art Décoratifs (MAD) devoting an exhibition to Paul Poiret in its year-long celebration of the centenary of art deco and the event that gave the style its name. Its chronological survey presents a mostly linear story of Belle Époque success on the ground floor, while the first floor is considerably busier, with multiple sightlines and sections that challenge visitors to pick a way through the displays of fine and applied art that now vie for attention with the clothes. Elsa Schiaparelli was exaggerating when she said of Poiret, ‘He died as Mozart died with not a single friend to follow his coffin’, but his failure in business allowed both contemporaries and successors to absorb his innovations or claim his legacy. MAD makes the point by presenting a selection of post-war ensembles from its own collection, some of which (an evening look from Yves Saint Laurent’s ‘Opéras – Ballets Russes’ of 1976, for instance, or a rose-inspired ‘Rochas’ gown of 2004 by Olivier Theyskens) seem closer to fancy dress than fashion.

The opening displays make the nature of Poiret’s innovations clear. As you enter, to the far left is a row of outfits from the maisons he designed for before setting up on his own in 1903. Floor-length day and evening dresses for first Jacques Doucet and then Worth required the wearing of an S-bend corset and wide shoulders, even leg-of-mutton sleeves, to emphasise the narrowness of their waists even further. To the right – and closer to the entrance – is a group of four evening gowns made between 1907 and 1924. A ‘Joséphine’ dress (1907) is a long, Empire-line affair, as its name suggests, but the other three immediately take us into a 20th century where hemlines are rising and corsets are heading for the exit. All three, tellingly, were gifts from Denise Poiret, who inspired and modelled her husband’s most advanced creations such as the ‘Lavallière’ (c. 1910), displayed here in an ivory silk satin version embroidered with silver bugle beads. The blouson V-neck top falls open at the neck to reveal a contrasting purple silk that repeats at the sleeves and hemline; the waist is created by a ruched sash. For a 115-year-old outfit, it looks completely up to date.

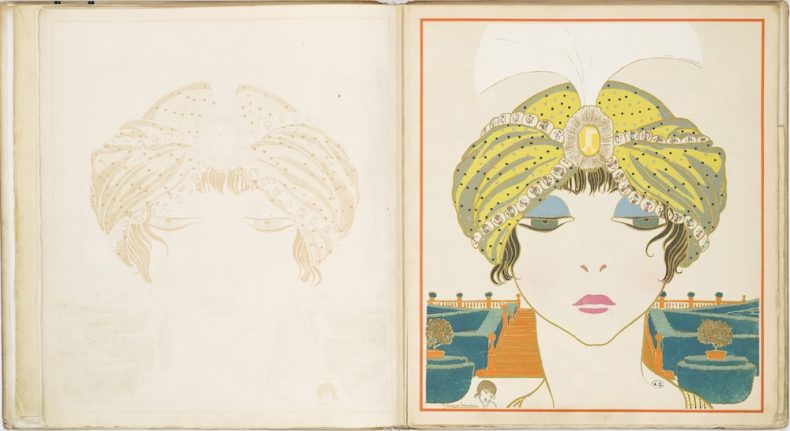

Poiret’s imperial phase, when he could do little wrong, was between 1909 and 1913. It began with Margot Asquith showing him her violet satin knickers when she came for a fitting and invited him to put on a teatime fashion show at her London residence, which happened to be 10 Downing Street; it ended with Poiret touring the United States at the invitation of department-store owners with Denise, an entourage of mannequins and 100 dresses in tow. This was the period when Poiret could still shape and reflect the tastes of those of his wealthy clients who, like the designer, had been bowled over by the Ballets Russes season of 1910 and by Schéhérazade as designed by Léon Bakst, in particular.

The orientalism popularised by the pre-war Ballets Russes was picked up by Poiret in the form of the jupe-culotte (split skirt) and ‘harem’ pants, but it also represented an imaginative world the designer was reluctant to abandon when fashions changed. In 1911, the ‘Thousand and Second Night’ party Poiret hosted at home (also home to Maison Poiret) for 300 of the most fashionable people in Paris was one of his greatest successes. However, in 1919, when he opened Oasis, an exotically inclined nightclub with weekly costume parties (also chez Poiret), he had fallen behind the times. After the First World War, Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, in contrast, mostly put aside its mistress-and-slave repertoire for crisp neoclassicism and costumes by the likes of Chanel. After being responsible for so many firsts – he was the first designer to launch a perfume; the first to have their work photographed for a magazine, by Edward Steichen, no less – Poiret was now failing to keep up. He disapproved of cubism (‘studio exercises and mental speculation’); the figure of the garçonne (‘cardboard women, with hollow silhouettes, angular shoulders and flat breasts’); and women who liked wearing beige or grey. Crucially, he was unwilling to scale up production or find a way of benefiting from the market in copies.

When Denise left him, Poiret is said to have told the governess, ‘Make sure to tell Madame to take anything she wishes.’ This mostly comprised, in the words of her granddaughter, ‘trunks and trunks and trunks and trunks and dresses’. While Poiret was forced to sell nearly all his possessions after bankruptcy, Denise kept everything she owned in meticulous condition for the rest of her life, along with detailed descriptions about how it was meant to be worn. When she finally opened her trunks in the 1960s to those outside her small circle, it marked the beginning of the revival in Poiret’s reputation. Upstairs at MAD, we can follow Poiret pursuing one failed venture after another, but downstairs it is a quiet act of conservation that conveys the best of his legacy.

From the September 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.