From the October 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unassuming in appearance and mild in flavour, the potato is taken for granted as a humble, everyday foodstuff. In fact, this modest-looking tuber has a remarkable history. Its origins are in South America, where it was a staple food for Andean communities. The potato was introduced from Latin America to Europe as part of the ‘Columbian Exchange’ – the transfer of plants – including tomatoes, maize and chillies – as well as animals and diseases, that followed Christopher Columbus’s voyage to the Americas in 1492. Today, the potato is the world’s fourth most cultivated food crop, after the three great grains, rice, wheat and maize.

Hardy, easy to grow and a good source of energy, the potato plant was cultivated by rural communities throughout Europe. European statesmen and rulers, seeking to ensure a well-nourished population, extolled the potato’s virtues as a useful crop. In Ireland, where the rural poor had to scrape a living on small plots of land, the productive and calorific potato plant was widely adopted as a staple. Writing of the state of Irish peasants in 1727, Jonathan Swift observed that they ‘pay great rents, living in filth and nastiness upon buttermilk and potatoes and not a shoe or stocking to their feet’.

With the arrival of potato blight in Europe during the 1840s, the Irish dependence upon one subsistence crop had dire consequences. With no other staple food, the repeated failure of the potato crop in Ireland, compounded by the intransigence of the British government, resulted in the Great Famine (1845–52), which caused an estimated million deaths from starvation, alongside mass emigration. This shocking event resonates powerfully in Irish culture to this day. In his poem ‘At a Potato Digging’ (1966), Seamus Heaney describes a potato harvest, contrasting it viscerally with the horror of the Great Famine, in which ‘putrefied potatoes’ lay in the ground alongside rotting bodies. In other poems, Heaney wrote affectionately of watching his father digging for potatoes – evoking the ‘cool hardness’ of freshly dug new potatoes – and of companionably peeling them with his mother as a boy.

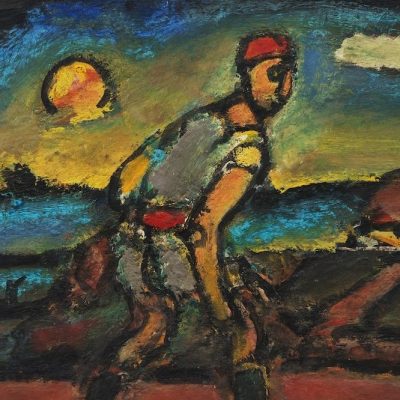

Given that potatoes grow underground, there is, aptly, an earthy quality to how potatoes are depicted in art. The development of blight-resistant potato varieties allowed it to be widely grown as an important food crop in Europe during the 19th century. A founder of the Barbizon School, the artist Jean-François Millet often portrayed the hard manual labour carried out by workers on the land. Millet’s painting Potato Planters (1861) depicts a man and woman planting potatoes – a crop with which they will feed themselves – and imbues both figures with a fundamental dignity. In Émile Zola’s novel Germinal (1885), about a mining community that goes on strike, potatoes are a vital food for the miners. Vincent Van Gogh was an admirer of Zola’s work and in 1885 he painted his only group portrait, The Potato Eaters (on view at Het Noordbrabants Museum as part of ‘De Aardappel’, which runs from 11 October–1 February 2026). Writing to his brother Theo, Vincent described his intent for the picture: ‘You see, I really have wanted to make it so that people get the idea that these folk, who are eating their potatoes by the light of their little lamp, have tilled the earth themselves with these hands they are putting in the dish, and so it speaks of manual labour and – that they have thus honestly earned their food.’

From a culinary point of view, the potato is remarkably versatile, surely one reason for its wide popularity. There are thousands of varieties but, depending on their starch content, potatoes are broadly classified as floury or waxy and are used accordingly. They can be cooked in numerous ways: baked, roasted, mashed, fried, boiled, braised, stewed, or steamed. It is, however, in its deep-fried incarnation as chips, frites or French fries that the potato is surely best loved. Although these irresistible deep-fried treats are now devoured around the world, when and where the chip was first created is much disputed, with both France and Belgium laying claim to the honour in the 17th, 18th or 19th century, depending on which origin story you choose.

The chip, of course, plays a key role in several national dishes: France’s steak frites, Britain’s fish and chips, America’s burger and fries. Much kitchen geekery has gone into obsessively exploring how to make the ‘perfect’ chip, with Heston Blumenthal creating the ‘triple-cooked chip’. McDonald’s best-selling item is its ‘World Famous Fries®’, featured on its menu since 1955. It’s estimated that McDonald’s sells more than 4,000 tonnes of its fries around the globe every day. The humble potato – the globe-trotting vegetable that became a staple food of the rural poor – is now big business.

‘De Aardappel’ is at the Het Noordbrabants Museum from 11 October–1 February 2026

From the October 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.