From the October 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

It started off, appropriately enough, with an unexplained phenomenon. In 1862, the Boston jewellery engraver and amateur photographer William H. Mumler took several self-portraits, and upon developing them discovered in one a diaphanous hint of a second figure – even though he had been entirely alone in his studio. His first instinct was that he had not thoroughly cleaned the glass photographic plate before reusing it. Entirely plausible, and almost certainly the case; but Mumler then consulted a leading advocate of the popular Spiritualist movement, who assured him that he had succeeded in photographing some sort of spectral emanation.

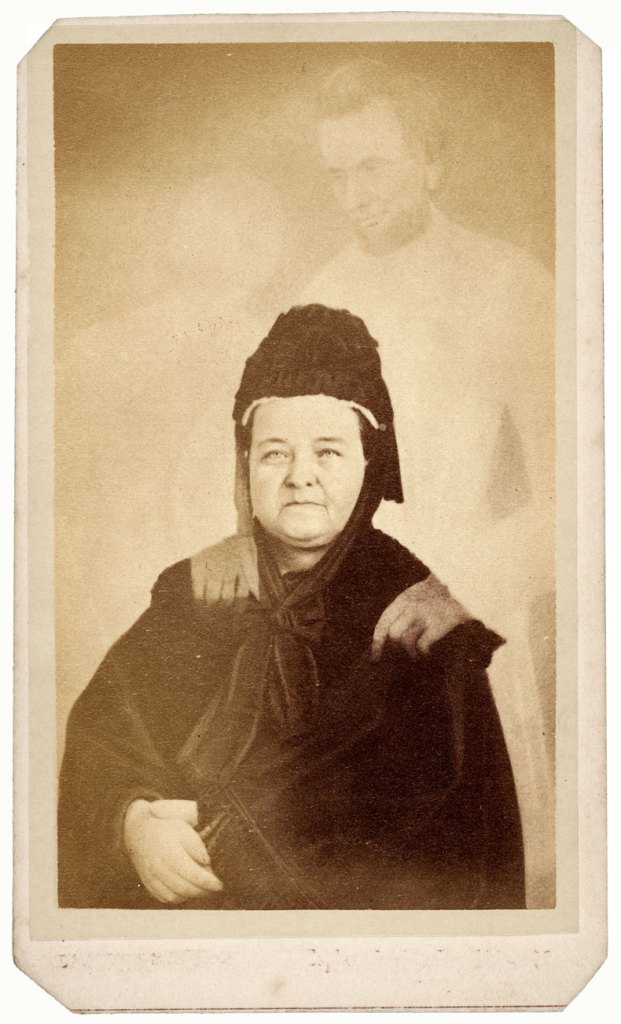

Thus ‘spirit photography’ was born – not quite the material of autumnal fireside ghost stories, but pleasingly uncanny and unsettling in its own way. Mumler and his numerous imitators soon set themselves up in business as photographic conduits to the deceased. The images, as a rule, were the kind of staid portraits associated with early photography, but also miraculously in the frame were ghostly apparitions of deceased relatives – sometimes resting their hands on the sitters’ shoulders, sometimes barely more than a spooky smear. Almost, one might think, like a double exposure was involved. Indeed, it’s likely that there were some photos created in this way, but since the sitter would need to be present for both exposures (to ensure that they didn’t become see-through too), it might have looked a little obvious what was going on when an assistant draped in a winding sheet came on set for the second shot. More often, spirit photographers would have created the effect by overlaying a second glass plate while developing the picture (having carefully quizzed the sitter in advance and selected a spectral figure with the required features).

Mumler charged $10 for a session – some 40 times the going rate for an ordinary portrait – but even then could not guarantee that the spirits would be ‘in attendance’. As a result, his clients tended towards the wealthier strata of society, most famously Mary Todd Lincoln, widow of the assassinated president, whom he photographed apparently receiving a shoulder massage from a translucent Honest Abe.

Therein, perhaps, lies the key to spirit photography’s mysterious popularity. Spiritualism was at its peak in the 1860s, but hung around like a restless wraith until well into the 1920s. It is easy to understand why it might have provided some kind of solace in the era of the American Civil War, when some 700,000 people were killed far away from their loved ones. (There is at least one instance of a woman being photographed with the ‘spirit’ of her deceased brother, only for him to come marching home again, entirely alive, shortly afterwards.) In Britain, too, it was hard to escape reminders of those who had passed on. Mourning clothes were especially prominent, fashionable even, in the wake of Prince Albert’s death in 1861 – Queen Victoria wore hers for the next 40 years, considerably longer than normal etiquette dictated. Amid such constant memento mori, the idea of making contact with the other side would have seemed reassuring, whether by means of tapping tables at a séance or a photographic shoot with an ethereal presence – and the Spiritualist movement gave it the superficial sheen of a rational system of beliefs.

It is all too easy – lazy, even – to dismiss the Victorians as credulous ninnies, unable to detect what to the eyes of 21st-century sophisticates are blatant examples of camera trickery. But to do so is to paint the 19th century, an era of relentless scientific and technological advance, as backward and primitive. Certainly, many were taken in by spirit photographs, not least because they wanted to believe; but photography was a comparatively new, ahem, medium, so few people were yet aware of what it was possible to achieve in a darkroom. Many of the keystones of scientific advance, too, were invisible to the naked eye, from electric current to Pasteur’s germ theory, so the notion that cameras might be capable of recording such things was not without plausibility. Indeed, it was given extra impetus with Wilhelm Röntgen’s discovery of X-rays in 1895; the ensuing photographs – of the bones in his wife’s hands, for instance – must, at first, have seemed even more outlandish than any double exposure of a woman wearing a sheet could hope to be.

Not everybody at the time was taken in by this chicanery. Plenty were well aware that spirit photographers were closer to confidence tricksters than exponents of the scientific arts. In 1869 Mumler stood trial in New York for fraud and larceny, with the great showman P.T. Barnum – no stranger himself to ripping off an easy mark – testifying against him. As evidence, Barnum engaged a professional (non-spirit) photographer to create a portrait of him with the eerie visage of Lincoln faintly discernible behind him, like a wallpaper Shroud of Turin. Experts for the prosecution cited nine separate methods that might have been used to fake pictures of the deceased. In the end, however, Mumler was acquitted, seemingly on the grounds that it was impossible to prove beyond reasonable doubt that he had used trickery as opposed to genuinely capturing phantasms on camera.

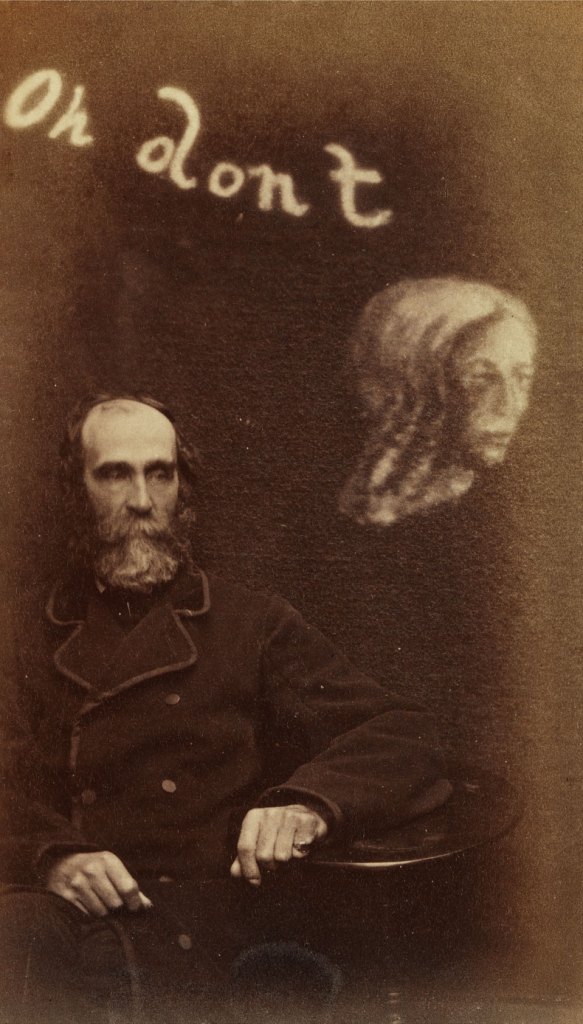

Leaving aside the circumstances of their creation, today spirit photographs have something of the appeal of outsider art. It is hard to believe they were ever taken seriously, but nevertheless there is something compelling about rigid, dour Victorians juxtaposed with floating heads that resemble Robert Freeman’s sleeve art for With the Beatles, or nebulous shapes that veer on abstraction. A selection of pictures by Mumler and his contemporaries can be viewed as part of the exhibition ‘Ghosts: Visualizing the Supernatural’ currently running at the Kunstmuseum Basel. Here you can see haunting apparitions galore, ectoplasm, ‘the development stage of a spirit form’ and more than a few images that now seem more comical than at first intended. An example by the British studio of F.M. Parkes features a hirsute sitter haunted, like Belshazzar, by a spooky graffito: the unpunctuated phrase ‘oh dont’ in a Tippex-like cursive above his head. Spirits were almost certainly involved in its creation – but most likely of the chemical kind, at the development stage.

‘Ghosts: Visualizing the Supernatural’ is at the Kunstmuseum Basel until 8 March 2026.

From the October 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.