From the October 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

On the morning of 27 September 1979, a group of non-professional, mostly self-taught Chinese artists set up an exhibition outside the National Art Museum of China in Beijing. Oil paintings, ink paintings, woodcuts and wood carvings were hung on fences and in trees. Huang Rui, Ma Desheng, Li Shuang, Bo Yun, Wang Keping, Yan Li, Yang Yiping and Ai Weiwei were among the 23 artists of what became known as the Stars Art Group or Xing Xing. It was closed by the authorities after three days but, following a large protest, reopened in November for another 10 days.

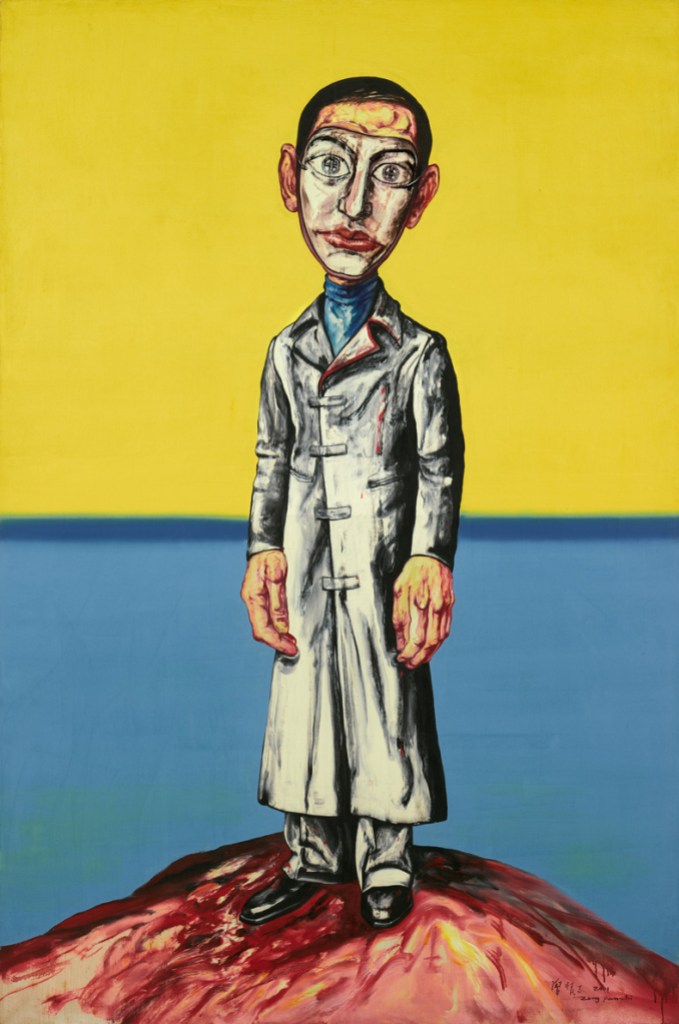

This was a significant moment for Chinese contemporary art – the birth of an avant-garde after Mao’s death and in the dawn of Deng Xiaoping’s era of ‘reform and opening up’. In 1980, a second Stars exhibition opened inside the museum. Far from socialist realist art, ‘serving the masses of the people’, as advocated by Mao, this work expressed personal visions and private anguish. By 1983, as political pressure mounted, the leading figures of the Stars Group were in exile. The ’85 New Art Movement brought together a second wave of artists, including Chen Zhen, Ding Yi, Liu Zhenggang, Wang Guangyi, Xu Bing, Yu Youhan and Zhang Xiaogang. Pursuing narrative painting, abstraction, conceptual art, installation and performance, they were influenced by traditional training as well as new access to Western art. The Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989 drove many into exile or underground. During the 1990s new groupings formed – the artists of ‘Political Pop’ (including Wang Guangyi, Yu Youhan, Li Shen and Liu Dahong), the younger leaders of the satirical school of ‘cynical realism’, Yue Minjun, Fang Lijun, and Liu Wei, and others such as Liu Xiaodong and Zeng Fanzhi.

Two Hong Kong gallerists pioneered the market in Chinese contemporary artists: Johnson Chang at dealership Hanart TZ, founded in 1983, and Swiss-born Manfred Schoeni, who opened his gallery in 1992 with an exhibition of Liu Dahong, following up in 1994 with a two-man show by Yang Shaobin and Yue Minjun. Nicole Schoeni of Schoeni Art Projects says, ‘My father believed in backing artists wholeheartedly – sometimes buying entire bodies of work – so they had the freedom to create without compromise.’ They sold to Westerners based in Hong Kong and mainland China, chief among them the Swiss ambassador Uli Sigg, and Guy and Myriam Ullens. In 1994 Chang introduced Chinese contemporary artists to the 22nd São Paulo Biennial, and in 1995 to the Venice Biennale. Schoeni was involved in exhibitions such as ‘China!’ at the Kunstmuseum Bonn (1996) that took these artists to wider global audiences. In 1996 the auction house Zhong Shang Sheng Jia organised the first sale within China dedicated to Chinese contemporary art. At that point there was little domestic interest, but many artists had established multinational collector bases, with international gallery support, enabling them to create substantial bodies of work.

In October 2004 Sotheby’s Hong Kong sparked what became an explosive market with a first auction dedicated to Contemporary Chinese Art. By 2006 Sotheby’s was selling works by some of these artists in evening sales in New York and London. Prices rose dramatically. In October 2007, Yue Minjun’s politically charged painting The Execution (1995) sold at Sotheby’s London for £2.9m (estimate £1.5m–£2m) – then a record for contemporary Chinese art. Early enthusiasts saw their holdings appreciate significantly, encouraging more works on to the market. In China in November 2006, Poly Auction sold Liu Xiaodong’s oil painting New Settlers at the Three Gorges (2004) for RMB22m (US$2.7m), more than twice its estimate.

The global financial crisis of 2008 knocked the wind out of the international market, with a further downturn inside China after 2012. But as Alex Branczik, Sotheby’s Chairman and Head of Modern and Contemporary Art, EMEA & Asia, London, says, ‘A lot of records were still made after 2008.’ Growth slowed, but was sustained globally by ‘some of our top collectors, looking for the best of the best’. In October 2013 Sotheby’s Hong Kong’s 40th anniversary sale saw a new record for a living Chinese artist – HK$180.4m (US$23.3m) for Zeng Fanzhi’s The Last Supper (2001). Ai Weiwei’s auction record was set in 2015 at Phillips London when a bronze set of Circle of Animals / Zodiac Heads was knocked down for £3.4m (estimate £3m–£5m). Major works by the big names at auction – Zeng Fanzhi, Zhang Xiaogang, Yu Youhan, Liu Xiaodong, Liu Wei and Liu Ye – found their way into institutional and major private collections. Chinese buyers, who entered the market in the early 2000s, now dominate, Nicole Schoeni says, ‘though Western collectors remain quietly committed’. She adds, ‘Artists such as Ai Weiwei, Cai Guo-Qiang, Liu Wei, Liu Xiaodong, Xu Bing, Yue Minjun, Zeng Fanzhi, and Zhang Xiaogang continue to be highly sought after.’ Branczik notes, though, that for the last five years Asian buyers have been showing strong interest in Western rather than Chinese contemporary art. Meanwhile, a dearth of quality works coming to auction has depressed prices. Sotheby’s Hong Kong has been testing the water with two major works – Zeng Fanzhi’s Society no. 3 (Mask Series 2001 no 3) (2001), estimated HK$14–24m, and Zhang Xiaogang’s Bloodline – Big Family No. 7: Siblings (1996), which at time of writing is expected to fetch HK$4m–$6m. ‘The market,’ Branczik says, ‘needs reassurance that these works have value.’

This autumn brings other stimuli. Hong Kong-based 3812 Gallery is opening a space in Whiteley’s, London, on 15 October with a solo show of work by Ma Desheng. This will focus on works inspired by the female form – a subject he first took on in the early 1980s, when he made the transition from woodcut to ink painting. According to Calvin Hui, co-founder of the gallery, Ma’s rare early ink works are highly prized – a female figure in ink from 1988 sold for HK$492,000, against an estimate of HK$30,000–HK$50,000, at China Guardian Hong Kong earlier this year.

Lisson Gallery, whose stable includes Ai Weiwei and Liu Xiaodong, opened its first solo presentation in London of works by Ding Yi in September. Curatorial director Greg Hilty notes the focus on this generation of artists by the Tate, the Met, the Guggenheim and the Pompidou – while Liu Xiaodong had a solo show, ‘Borders’, at Dallas Contemporary in 2021. He also points to recent rapid growth of audiences in the large Chinese diaspora. Shanghai-based Ding Yi is, he says, ‘hugely successful and revered in China’. Hilty believes that his current work – ‘with its conceptual grounding and abstract craftsmanship’ – reaches out beyond the local context, and that recent shows in Wales, France and Switzerland suggest this is ‘a very good time to bring him on to the international stage’.

Meanwhile, White Cube has just opened Cai Guo-Qiang’s first solo show in London for 20 years, ‘Cai Guo-Qiang: Gunpowder and Abstraction 2015–2025’. A spokesperson says: ‘Ahead of Cai’s London exhibition, we’ve already seen strong sales of his work at Art Basel, where we placed three major paintings on our booth: Red Birds (2022), which sold to a European fine art institution for $1.2m, alongside Trish’s Peony No. 2 (2023) and Natural Poppy Flower (2016), each acquired for $700,000.’ At Art Basel Paris the gallery is also showing work he has created in collaboration with his self-developed AI model. The avant-garde is still evolving.

From the October 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.