The ‘Enchanting Modernism’ exhibition at KMSKA in Antwerp features the cubist sculptor Aleksandr Archipenko in its full title, and a host of renowned 20th-century artists from Natalia Goncharova to Fernand Léger in its retrospective of the Paris-based cubist group La Section d’Or. Its principal aim, however, is to reintroduce Marthe Donas – one of Belgium’s first notable women painters of the century and a well-regarded member of the group at the time – to the European modernist canon. A huge amount of effort has gone into this, with sculptures thought too fragile to travel being transported to Antwerp, and Donas paintings thought lost being tracked down and exhibited for the first time in over a century. The result is a spectacular success.

This is in large part thanks to the curators’ careful contextualisation of Donas and her work. They emphasise that she was not the only woman in her circles: Guillaume Apollinaire noted that La Section d’Or included plenty before the First World War, with more featuring in its post-Armistice relaunch. For Donas, it was the war itself that prompted her association with the movement: the German invasion of Belgium allowed her to move to the Netherlands, then Ireland, then the Côte d’Azur, freeing her from her authoritarian father, who forbade her to pursue art. The exhibition links Donas to the men who changed the direction of her work, most prominently her sometime lover Archipenko, but they are prudent in showing how she forged her own path and influenced the male artists with whom she often exhibited, sometimes under the genderless pseudonym of Tour Donas.

Donas’s time at the centre of European modernism was brief: the exhibition focuses on her work after she moved to Nice in 1917 and met Archipenko, swiftly learning from him and André Lhote and developing her own brand of cubism. It ends with Donas taking a leading role in reconstituting La Section d’Or for a large touring exhibition in 1920, featuring her work alongside Theo van Doesburg’s striking poster, Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov’s costumes and paintings by international artists from Albert Gleizes to František Kupka. By then, cubism was going out of fashion, soon to be overtaken by Surrealism. Donas did not connect with Breton’s movement, which soon became the most vibrant style of painting in France and Belgium, and illness and family commitments took her away from her artistic milieu. By the end of the 1920s she had stopped making art: she resumed 20 years later, working figuratively, but her reputation rests on her brief flourishing around La Section d’Or.

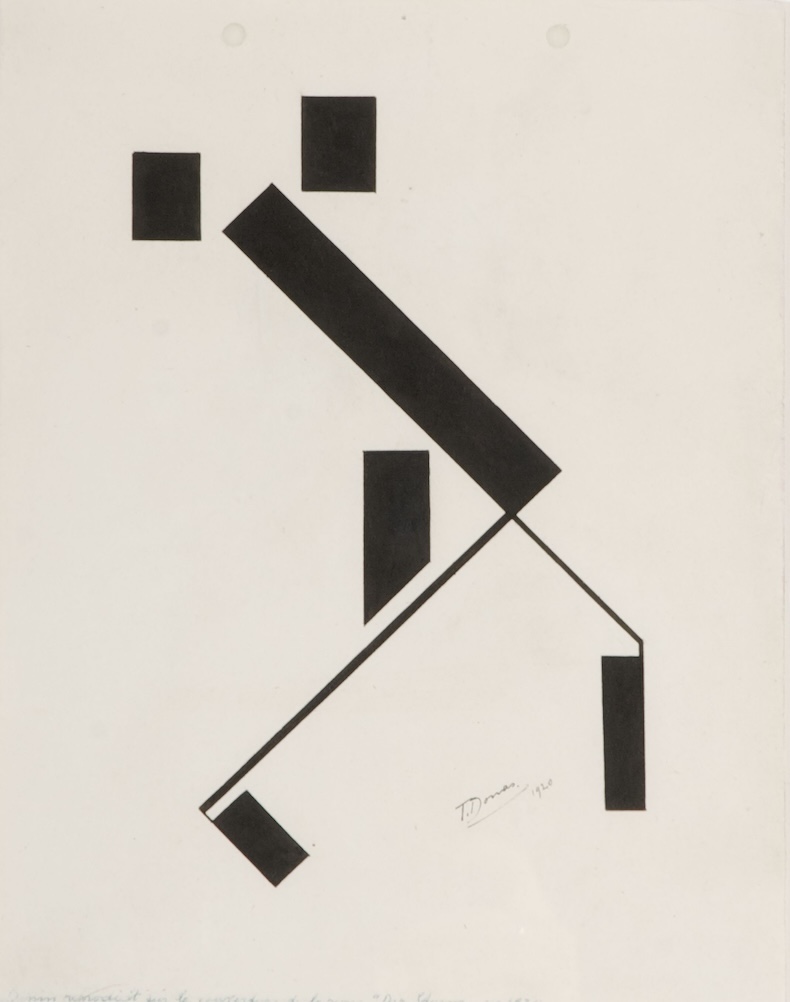

The shaped paintings that dispense with the rectangular frame, made a year before Hungarian Constructivists did something similar, mark Donas’s most significant innovation during a period in which innovation was paramount. Such experiments always grew out of the dialogue of artists with their contemporaries, and this paring down of the canvas drew from Archipenko’s use of negative space in sculpture, in which he reduced the human body to a semi-abstracted minimum without facial features, clothes or genitalia. Sharing Archipenko’s interest in how to portray dancing, Donas painted The Tango (1920) for the cover of German Expressionist magazine Der Sturm, a Constructivist constellation of blocks and diagonal lines that was far more minimal than any of her previous works. This may have given an international audience the wrong idea – her work was sometimes more figurative and seldom as stark. The use of silk and sand in her work, and softer colours such as neon pink in her abstract compositions, led contemporary critics to consider her a more ‘feminine’ artist and place her in the shadow of her male peers.

Donas endured multiple disappearances: she left the modernist scene; her works were rarely exhibited and her historical profile has been low. Curator Peter Pauwels has worked for decades to find her paintings, besides a few held in Antwerp and Paris, and his efforts show Donas as a vital player in a French art scene that welcomed immigrants from all over Europe. It should mean that her paintings and drawings at last get to travel: they certainly deserve to reach a far wider audience.

‘Donas, Archipenko & La Section D’Or: Enchanting Modernism‘ is at the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp until 11 January 2026.