From the November 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

There is a danger of smoking becoming chic again. I blame artists. The choreography of cigarettic gestures is just too compelling, pictorially, to relinquish. Cigarettes perform as an extension of the arm, adding angular elongation to the expressive hand and wrist. Exhaled smoke offers a portrait of breath, warm from its permeation of the body’s branched interior. Smoke mists the view, blurring the edges of forms and casting scenes into mannered ashy paleness. For painters and cinematographers alike, illumination from a struck match or burning tip explodes drama into a dim scene.

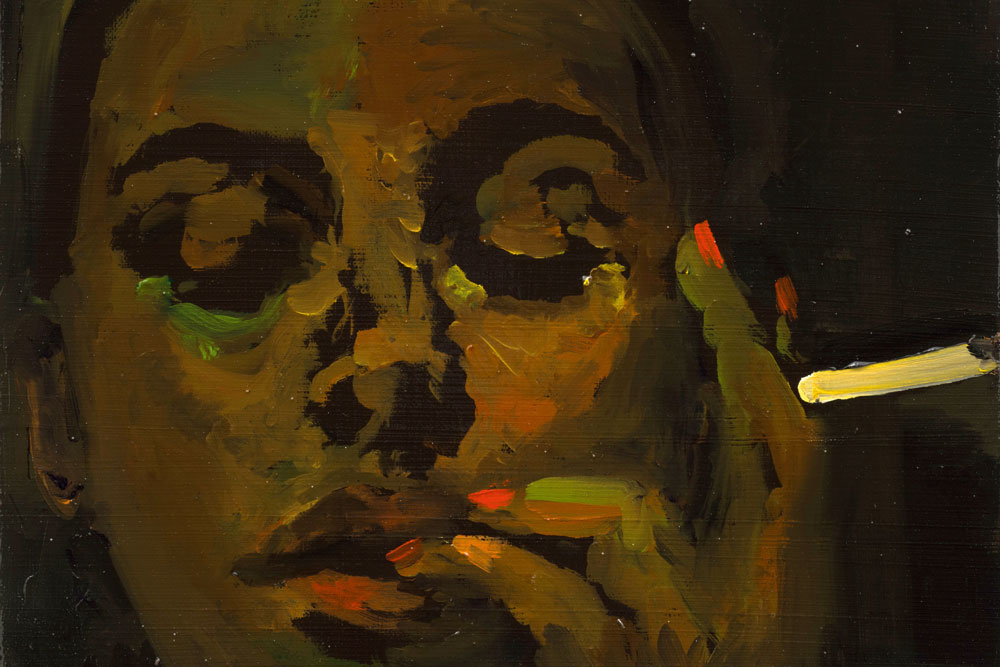

The hot amber of a lit cigarette is echoed in red nail lacquer and the faint reflection of coloured neon on a woman’s skin in Danielle Mckinney’s Soliloquy (2025). It’s a painting of intimate scale, with the top half of the woman’s face and the length of her cigarette occupying its width. Her eyes are closed and her fingers stretch between the extended thrust of the cigarette and the velveteen suggestion of her gently parted lips. This is a private moment in a darkened room. Mckinney is interested in drawing form out of darkness by dressing it with the faintest coloured light. Painted in a palette structured around rich tones of brown, hers is a nocturnal world in which Black women are depicted at rest in barely lit rooms.

Mckinney’s women are self-contained, not waiting or performing, just present. In a few paintings they catch the gaze, but more often they seem unaware of the painter’s intruding eye, or ours. Together with the low lighting, soft surfaces and elegant interiors, the cigarettes contribute to a vocabulary of private luxuriousness, suggesting liberation and a nostalgic vision of the modern woman c. 1975. Sometimes a cigarette is just a cigarette, but sometimes the implication of self-pleasuring it carries is hard to overlook: a soliloquy is, after all, high drama for a cast of one.

Whether in a pipe or cigarette, smoking tobacco was associated with deep, creative thought in the 19th and early 20th centuries: Sigmund Freud himself considered his cigars an essential aid to contemplation. Within Euro-American cultures, smoking was an occupation respectable only for men. Thus, the cigarette also became a sword of honour for the ‘new woman’, denoting intellect, independence and disdain for the rules of a society that denied her education, employment and suffrage.

In 1896, the American photographer Frances Benjamin Johnston staged a self-portrait in which she appears poised mid-conversation before a fire, skirts hoisted to the knee, with a cigarette jabbing the air before her right hand and a tankard of beer in the left. Johnston is performing for her own camera, but this -petticoat-flashing, cigarette-smoking persona was also an honest proclamation of an unconventional and unusually independent life. A photojournalist whose camera captured Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders, Isadora Duncan’s dance troupe and a clutch of US presidents, she travelled alone and remained – as euphemistically as you might care to read it – unmarried. Paula Rego borrowed something of Johnston’s spread-knee’d, tobacco-puffing persona for her spiritual self-portrait The Artist in Her Studio (1993).

Smoking’s transgressive associations with modernity and independence were, at the turn of the 20th century, a badge of pride for white women of status. This was not a performance of modernity available to women of colour and others for whom hard work was a birthright rather than an aspiration. In Édouard Manet’s Plum Brandy (c. 1877), the young sitter’s ungloved hands and unlit cigarette mark her out as a working-class woman. She is often assumed to be inviting the approach of a man with a lit match (indeed, she is often assumed to be a prostitute). We might just as well assume that she is happy sitting down alone at the end of a hard day’s work – like Mckinney’s women, she seems comfortably lost in her own thoughts.

Ellen Andrée, the model for Plum Brandy, is one of the many female figures that Lisa Brice has liberated from the canvases of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists and used to populate her world of painting, drinking, resting – and invariably smoking – modern women. Brice’s women wield the paintbrushes of creative power and drag on the cigarettes of bohemian abandon. They gaze with blank eyes that deny access to their interior lives – you can look, but you are barred from participation in their world. None of Brice’s women invite the approach of a man with a lit match.

In their former incarnations they were models – actresses, prostitutes and other working women – performing roles marked out for them by painters who paid for their time (and often shared their beds). In Brice’s hands they are permitted the repose, self-determination and creative agency that gender, class and race placed out of reach in their own time. Their cigarettes send licks and curls up the surface of the canvas in a rhythmic pattern. Tendrils spill through half-open doors. In Brice’s world without men, as in Mckinney’s nocturnal interiors, these glowing tips and gauzy emissions point to pleasure, self-reliance and reverie, but also to inspiration. The smoke is more than incidental. A cigarette directs attention. It signals belated enjoyment of the modern bars and nightclubs that were closed off to respectable women of the late 19th century – among them the Impressionist painters Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot. These were spaces in which ideas were exchanged, alliances formed and human drama observed, between trails of tobacco smoke.

‘Danielle Mckinney: Second Wind’ is at Galerie Max Hetzler, London, until 1 November. ‘Lisa Brice: Keep Your Powder Dry’ is at Sadie Coles, London, until 20 December.

From the November 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.