View of Jubilee IV (1985–87) by Lynn Chadwick in the grounds of Lypiatt Park, Gloucestershire. Photo: Tanguy Beurdeley; courtesy Lynn Chadwick Estate/Perrotin

‘Four things to see’ is sponsored by Bloomberg Connects, a free arts and culture platform that provides access to museums, galleries and cultural spaces around the world on demand. Explore now.

Each week we bring you four of the most interesting objects from the world’s museums, galleries and art institutions, hand-picked to mark significant moments in the calendar.

On 12 November 1840, Auguste Rodin was born in Paris. He would go on to revolutionise sculpture with his radical approach to bronze, emphasising raw tool marks and rejecting the smooth surfaces and idealised forms of classical sculpture. In doing so he fundamentally changed sculptural practice for good.

Bronze, humanity’s first artificial alloy, has been used by sculptors for over 4,000 years, but it was in the 20th century that its expressive potential was most fully and variously realised. Modern artists abandoned bronze’s traditional association with heroic commemoration and classical perfection, and began to focus on capturing psychological ambiguity to a greater degree than ever before. They celebrated the casting process rather than concealing it, allowing seams and imperfections to become expressive elements. From Rodin’s assembled fragments of body parts to contemporary artists’ mixed-media approaches, modern bronze sculpture demonstrates how ancient materials can articulate distinctly contemporary concerns about identity, mortality and the human condition.

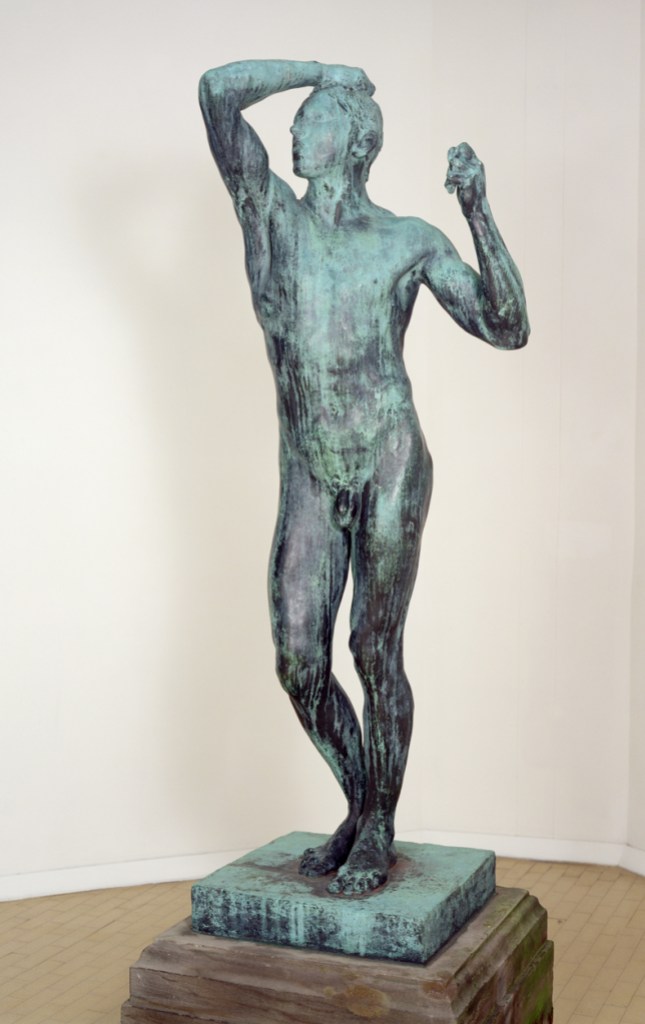

The Age of Bronze (1877/1906), Auguste Rodin

Leeds Art Gallery

Exemplifying the elegance of Rodin’s male figures, this sculpture announced in its title that the prehistoric material had entered a new era. Several versions of this sculpture exist but the version in Leeds Art Gallery is the only one with a distinctive green patination, having been left outside for many years in a North Yorkshire garden. The figure was considered so lifelike when Rodin first exhibited it in Paris in 1877 that he was accused of making the cast from a life model, and successfully proved in court that he had based it on photographs, which was the academic dogma at the time. Click here to learn more.

Walking Madonna (1981), Elisabeth Frink

Cathedral Close, Salisbury

Frink’s Madonna stands on the slimmest of pedestals among visitors to Salisbury Cathedral, her face at eye level to make her seem more like an equal than an object of worship. The bronze figure strides forward with grim determination, her slender form echoing the gothic architecture behind while her rough-textured robes suggest both austerity and suffering. One of Britain’s most prominent female sculptors, Frink brought religious iconography down to earth, creating a Madonna who embodies endurance rather than serenity. Click here to discover more.

Jubilee IV (1985–87), Lynn Chadwick

Lypiatt Park, Gloucestershire

One of several artists who helped put Britain on the map for sculpture in the post-war years, alongside William Turnbull, Eduardo Paolozzi and Reg Butler, Lynn Chadwick developed an unmistakeable style in bronze, creating a lively cast of haughty, elegant humanoid figures as well as a range of abstracted creatures – dogs, wolves and, most memorably, insects. The grounds of Lypiatt Park, his manor house in Gloucestershire, are filled with these spiky characters, and though their hard edges and featureless faces may seem intimidating at first, seen all together they take on an almost endearing quality. Click here to find out more.

Rosebud (2021), Huma Bhabha

Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College, Poughkeepsie

Bhabha’s enigmatic sculpture merges organic and anatomical forms into a meditation on memory and mortality, its title referring to the dying protagonist’s final word in Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane (1941). The metre-high bronze resembles a flower bud emerging from bare feet, with a small phallus attached like a leaf, suggesting themes of birth, sex and death. The work’s agitated, knobbly surface reveals every manipulation of the original clay – fingertips, knife cuts, additions and subtractions that bring us closer to the artist’s process. This contemporary approach to bronze embraces imperfection, rawness and Bhabha’s physical engagement with her materials. Click here to read more.

‘Four things to see’ is sponsored by Bloomberg Connects, a free arts and culture platform that provides access to museums, galleries and cultural spaces around the world on demand. Explore now.