From the December 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

The exhibition ‘Sixties Surreal’ at New York’s Whitney Museum explores Surrealism not at its Parisian roots but decades later, as an expressive mode in American art. It is a show of light and dark. Surrealism influenced art of many moods, from the gutter wit of Claes Oldenburg’s Soft Toilet to Lee Bontecou’s ominous, machine-like reliefs.

With its conceptual roots in psychoanalysis, Surrealism was a mode impeccably suited to a mid-century American population in thrall to self-examination. The Surrealists’ fascination with dreams chimed with the psychedelic revelations of flower children, and their upfront engagement with sexuality with the liberatory tenets of free love. Juxtapositions achieved through collage proved a subversive tool for revolutionary social movements. Among the revolutionaries was the feminist Martha Rosler, whose activist art pasted pornographic images of women’s bodies on to adverts for domestic appliances, suggesting both as goods available for ownership. Swerving literal representation, Surrealism also offered a powerful means by which to explore the violence of the era both at home and abroad.

Midway through the period explored in ‘Sixties Surreal’, the historian Richard Hofstadter identified a tendency he dubbed, in the title of an essay of 1964, ‘The Paranoid Style in American Politics’. The paranoid style encompassed qualities of ‘heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy’, and was characterised by ‘paranoid modes of expression by more or less normal people’ in which ‘the feeling of persecution is central [and] systematized in grandiose theories of conspiracy’. Just as the Surrealism of 1920s Paris offers a way to read American art of the 1960s, so Hofstadter’s concept of paranoid style offers well-tuned tools with which to approach the politics of our time.

Hofstadter used the term, he wrote, ‘much as a historian of art might speak of the baroque or the mannerist style. It is, above all, a way of seeing the world and of expressing oneself.’ If Hofstadter can plunder art history, I feel no compunction about appropriating his coinage in return, for I can think of no more appropriate phrase to characterise this moment in American art.

Recently shown at David Zwirner’s New York gallery, Sasha Gordon’s paintings embody paranoid style at its most apocalyptic. It Was Still Far Away (2024) seats the artist’s likeness on a picnic blanket in unpopulated parkland. In isolated oblivion, headphones covering her ears, she remains intent on trimming her toenails even as they are warmed by the hot pink glow of an exploding mushroom cloud erupting in the middle distance.

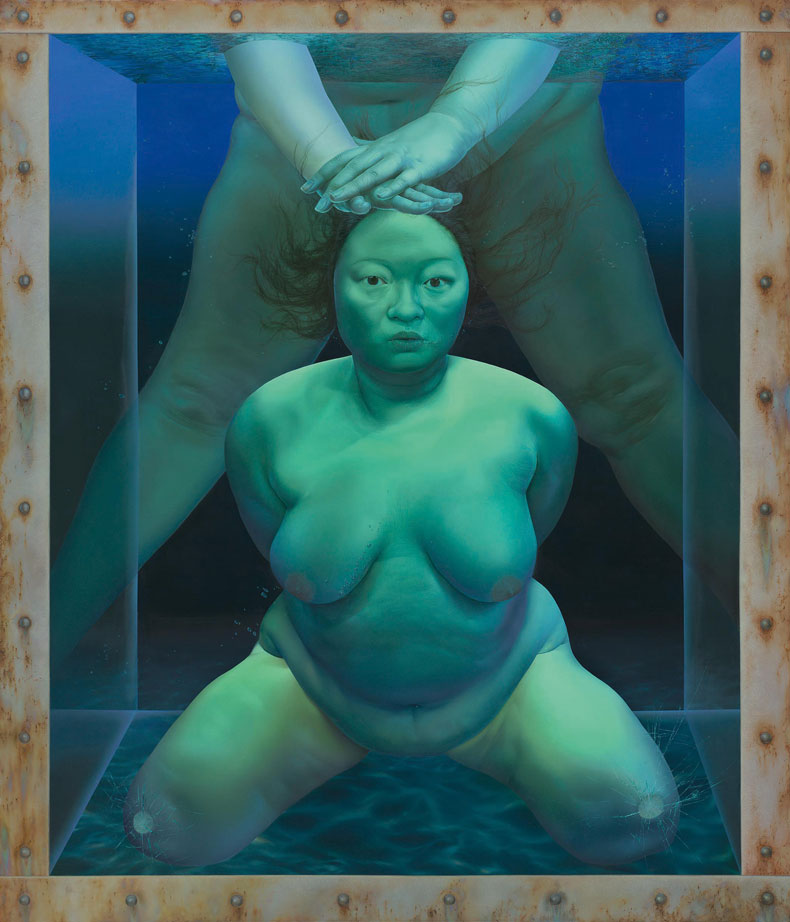

It Was Still Far Away was followed by a gallery of monumental paintings, each of which embodies acute psychological harm of one sort or another. The borders of Pruning (2025) are painted like strips of metal studded with bolts, between which Gordon appears, bound and naked, staring out from a tank of water, while a naked figure bears down on her head, keeping her submerged.

The figures in Petrified (2025) are both encrusted with muddy clay, one lying on the grey puddled ground, the other striding forward victoriously with a rope. Winning or losing seems immaterial, for there is nothing in this denuded scene with its swampy ground, ruined barn and chipped picket fence worth fighting for. In A Visitation (2025), Gordon again appears doubled, isolated within a cone of light in a dark room. One body slumps back over a chair – dead, dreaming or unconscious – while the other looms furiously, fingers digging deep into the flesh of the other’s shoulders.

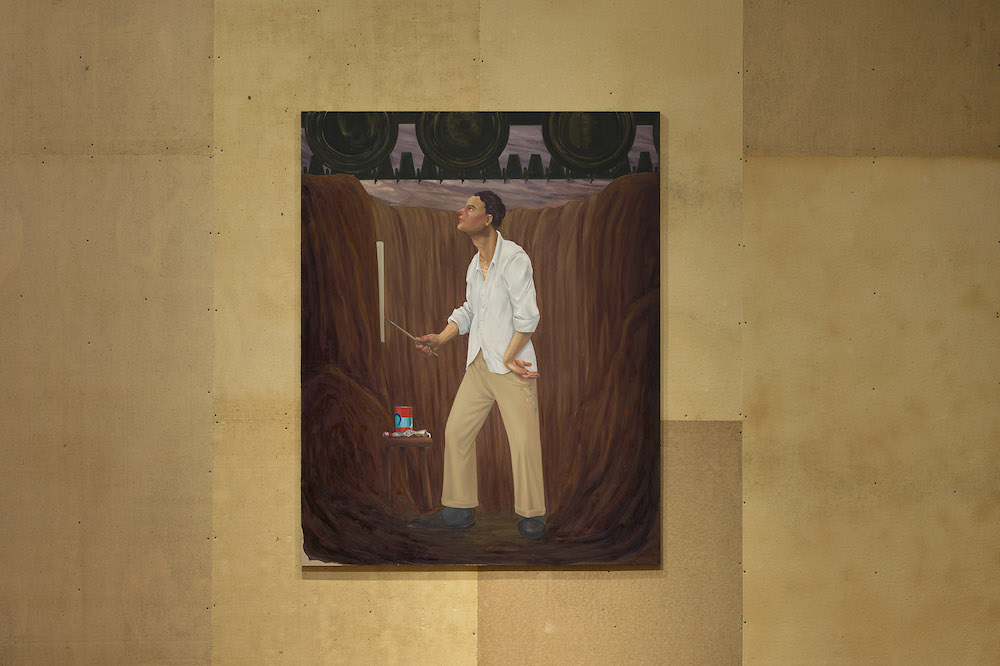

In part, Gordon’s paintings engage with the question of how (or perhaps why) to make art at a time of war and political tumult. It is a question that famously bedevilled Philip Guston, and one revisited by Nicole Eisenman in her 2024 painting Fiddle V. Burns (first shown at Sadie Coles HQ in London last year, now displayed at 52 Walker in New York). Fiddle V. Burns pictures the artist in a pit in the ground, straining, brush in hand, to catch a glimpse of the world beyond while the caterpillar tracks of a military tank roll above their head. Is painting in a time of crisis merely fiddling while Rome burns (or performing a pedicure while the world explodes), or is it the artist’s duty?

Gordon’s paintings also engage with the broader field of paranoia – intrusive thoughts, catastrophising, panic, errant yearnings. These are aspects of paranoid style that she holds in common with other artists showing in New York, among them Nayland Blake. This autumn Blake took over both of Matthew Marks’s Chelsea galleries. One building was home to a survey of sculptures and videos made in the 1990s during what we are now unfortunately obliged to recognise as the Culture Wars: Round One. The front end of the other building carried an exhibition Blake curated of small works with hand-made appeal. A surprise lurked behind a barricaded door: the gallery’s back room outfitted as a combined therapy suite and sex dungeon, entitled Session.

At the end of its wipe-clean couch were strung tin cans, each labelled with a potential betrayal – of family, of class, of community. The walls carried a battery of instruments, ranging from sexual apparatus to a small tinsel Christmas tree. Here was a room in which to feel the weight of guilt, the quality of paranoia, and to seek its expurgation. Blake noted the two professions that refer to appointments as a ‘session’: the psychoanalyst and the professional dominant. Not mentioned on this list, but implicated, is that exquisitely sensitive paranoiac, the artist.

From the December 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.