The Royal Society of Medicine (RSM) is to sell some of the most prized books in its historic library at Christie’s, London, on 10 December. The sale consists of 99 lots chosen from across the collection, including rare and unique volumes, such as the library’s celebrated copy of English physician William Harvey’s pioneering physiological study of 1628, Exercitatio anatomica de motu cordis et sanguinis in animalibus (‘An Anatomical Exercise on the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals’). By the RSM’s own account, the book, one of only 55 copies known, is the rarest book in its library. Christie’s has estimated the value of the sale overall at £2.2–£3.2m.

If Christie’s estimates are reached, the proceeds would represent more than 15 per cent of annual revenue for the RSM, which ended 2024 with income of a little more than £14m – a slight surplus. According to the Charity Commission, this comes on the heels of three years of substantial losses, totalling some £8.1m from 2021–23. Christie’s (to whom the RSM referred all comment) says that the sale is not intended to address budget shortfalls or amortise debts; rather, it is to invest in improvements, including updating facilities, increasing the organisation’s digital offering and new education initiatives. These schemes, it explains, were previously the subject of unsuccessful funding applications.

Among the lots to be sold are landmark works in the history of medicine, many of which predate the founding of the Medical and Chirurgical (surgical) Society, forerunner of the RSM, in 1805. By 1907, the society had expanded to incorporate 15 other medical associations, together with their libraries and archives. It now boasts one of the largest collections of its kind in Europe, with some 400,000 volumes, reflecting the dizzying complexity of medical history over the last two centuries.

The library also reflects the collecting interests of generations of distinguished scholars, including the legendary bibliophile William Osler, one of the co-founders of Johns Hopkins University, and Regius Professor of Medicine at Oxford from 1905–19. Osler obtained a number of the most significant volumes in the library, including Harvey’s Motion of the Heart and Blood, presented to the library in 1917, which headlines the sale.

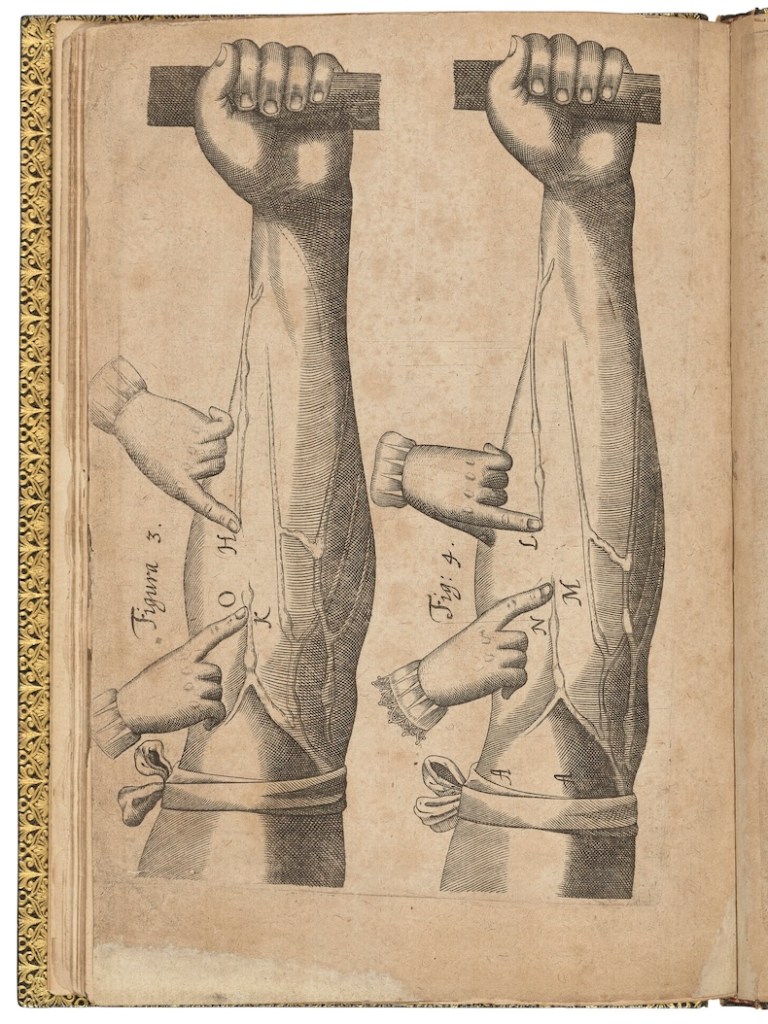

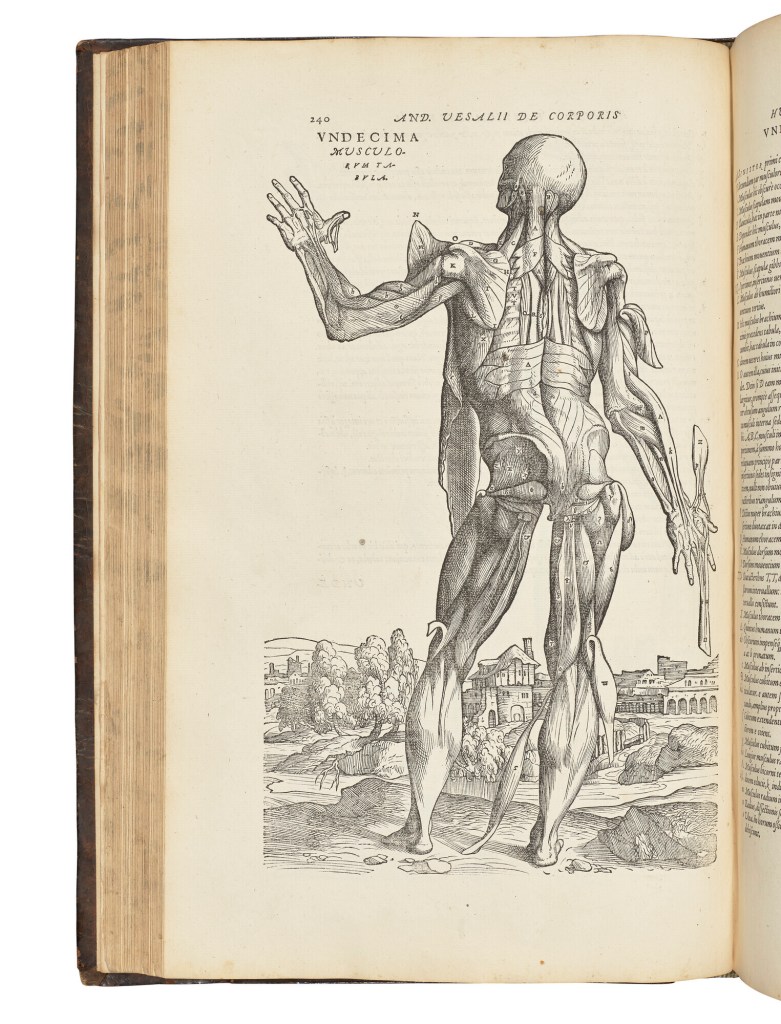

Also slated for deaccession are spectacular anatomical atlases, such as a first edition of Vesalius’s De humani corporis fabrica (1543) and five anatomical works by Gautier d’Agoty. In addition, irreplaceable manuscript materials and personal copies of works are to be shed, such as a presentation copy of Johann Remmelin’s A Survey of the Microcosme (1675) once belonging to the actress Nell Gwyn, and an autographed printing of Florence Nightingale’s tract criticising the parlous state of maternity hospitals (1871). James Parkinson’s Essay on the Shaking Palsy – the first detailed description of Parkinson’s disease, in 1817 – also appears, together with a group of letters by the vaccine pioneer Edward Jenner.

Christie’s explains that selections for the sale were made after extensive back and forth with RSM decision-makers. Yet it is hard to see how certain items were deemed expendable, such as 22 early photographs by Hugh Welch Diamond and his contemporaries of psychiatric patients from the Surrey County Lunatic Asylum, made in the 1850s. Photographs by Diamond are exceedingly scarce and represent major developments in psychiatric and photographic history. Diamond theorised that portraits made of patients could be used to both document and treat them, since sitters could be shown their pictures to help them better understand the state they were in.

The sale was partially previewed in New York in October, reflecting Christie’s international ambitions for the sale. Many items may nonetheless face export scrutiny, since they could be deemed integral to the understanding of history of science, medicine and art in Britain.

A senior official at the Department for Culture, Media and Sport would say only that the sale is a matter for the Royal Society of Medicine, which operates independently of government. It might be supposed that the partial dispersal of a collection as significant as the RSM would be a matter for the public interest, and that government would have a stated position on the retention of objects of heritage interest, notwithstanding the obvious current lack of funds.

For good or ill, the sale will soon arrive at the desk of the RSM’s new chief executive, Rachel Lambert-Forsyth, who assumed her post in November. The RSM declined to comment.