From the February 2026 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

At Aspinwall House, the main venue for the Kochi-Muziris Biennale (until 31 March), one of the first works you encounter is Only the Earth Knows Their Labour, an installation by Birender Yadav. The installation takes the form of a brick kiln recalling the ones in Mirzapur in Uttar Pradesh, near where the artist was born – but it’s conspicuously empty. The seasonal migrant workers who operate these kilns, often under conditions of bonded labour, are absent. Instead, their presence is suggested through terracotta renderings of clothing, tools and fragments of bones and bodies. Made from the same material these individuals handle daily, Yadav’s display makes visible the labour and power inequalities underpinning the production of the material world.

The biennial itself, which opened in December, was launched in 2012 in the city in Kerala. As India’s first contemporary art biennial, it has long attracted goodwill for supporting contemporary practice in the subcontinent and for the enthusiasm with which it has been embraced by the city. Run by a charitable trust, the Kochi Biennale Foundation, this year’s edition is curated by the Kolkata-born artist Nikhil Chopra and his Goa-based organisation HH Art Spaces.

In recent years that goodwill has been repeatedly tested. After the fourth edition, which opened in 2018, the biennial faced reports of financial mismanagement, missing and delayed payments to contractors and an allegation of sexual assault that led to the resignation of one of its co-founders, Riyas Komu. The fifth edition was delayed because of the pandemic. Then, in December 2022, on the eve of its scheduled opening, it was postponed by a further 11 days – prompting participating artists to publish an open letter alleging disorganisation, a lack of transparency and an absence of good faith in the face of their own ‘labour of love’.

The sixth edition opened against this backdrop at a point when shortcomings are hard to dismiss as growing pains. Since the last edition, the foundation says, it has ‘undergone a comprehensive restructuring to strengthen its governance, operational efficiency, legal compliance and financial management’ – including the appointment of a new chair (Venu Vasudevan, former chief secretary of Kerala) and CEO (management consultant Thomas Varghese). Perhaps conscious of the previous year’s bumpy start, Chopra framed this edition less as a singular event than ‘an invitation to embrace process as methodology’, supported by ‘friendship economies’. So, what has that meant in practice?

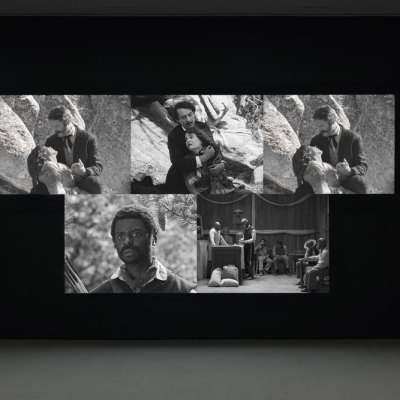

This year, 66 projects from more than 25 countries are spread across 29 venues, from warehouses to heritage buildings – the largest to date, it claims, in terms of locations, square footage and budget. When it comes to the artists, the roster is strong and rewarding. International figures such as Ibrahim Mahama and Marina Abramović lend star power, but the exhibition’s most compelling contributions come from mid-career to more established artists working across India. Many operate outside the country’s major metropolitan centres, bringing practices shaped by local contexts rather than international exhibition circuits.

For example, Kulpreet Singh’s film installation Indelible Black Marks transforms crop burning by farmers in Punjab into arresting choreography. Despite its effects on air quality, the practice persists in the absence of government support for alternative methods. Pallavi Paul’s cinematic work Alaq draws on her encounters with frontline workers and grave-keepers during the pandemic, assembling fragments of image and sound into a meditation on death, grief and ritual. Prabhakar Kamble’s Vichitra Natak (Theatre of the Absurd) confronts the logic of the caste system through assemblages made in collaboration with craftspeople – so often drawn from marginalised communities – alongside symbolic found objects and a mural referring to the violence faced by the first Dalit women to appear in Indian cinema. Faiza Hasan’s optical illusion Kal – a frothy wave made using thin metal leaf – sprays across the floor in an ocean-facing room, with a series of small self-portraits next to it unveiling a tension between the temporary and the permanent.

Unfortunately the opening of the sixth edition was beset by problems uncomfortably familiar from previous years. On both the preview and opening days, large parts of the exhibition were unfinished, with many installations still being assembled as visitors arrived – entrances sealed off, captions missing, screens inactive, a frantic spinning of ladders and boards. Journalists and other professional attendees were invited to roam around active building sites while artists and builders rushed to complete works and prepare rooms in situ. The organisers say that this improvisational approach was intentional: ‘Rather than delivering a polished final spectacle, the aim is to bring visitors into the act of making and showcase the energies of creativity, experimentation and exploration by envisioning the Biennale as a growing organism.’

For artists, however, working this way meant missing out on valuable exposure to and conversation with collectors, curators and members of the press. Working this way can also take a personal toll. Several artists voiced frustrations at the lack of organisation, describing the impact on their wellbeing and working hours.

In this context it’s reasonable to question the event’s scale. The biennale hints at Kochi’s ‘resource realities’ but if funding or labour constraints are the problem, the sheer number of venues and commissions feels irresponsible in the face of persistent logistical failures that can no longer be dismissed as one-off.

The schism is particularly striking when you consider the content of the exhibition. Many artists deal with the ethics of labour, inequality, precarity and extraction – dynamics that the global art world is not immune from. While ‘process as methodology’ is a laudable aim, it must extend beyond merely demonstrating the act of art-making to the conditions that art is made within. In Kochi and beyond, that means valuing care and operational efficiency as highly as ambition, vision and the benefits that ‘friendship’ brings.

So where does that leave the Kochi-Muziris Biennale? A month after it opened, its president and co-founder Bose Krishnamachari unexpectedly resigned from his post, citing pressing family reasons. His departure opens room for a new creative leader to take on the reigns and set a new course. Who and what that will be remains to be seen, as will what this new chapter will mean for the biennial’s future.

The Kochi-Muziris Biennale is at Aspinwall House and various venues across Kochi until 31 March.

From the February 2026 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.