From the February 2026 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

For a visitor to London in the 1840s, the giant subterranean kitchens of the brand-new Reform Club were an unmissable sight. Flamboyantly presided over by chef Alexis Soyer, who had worked alongside Charles Barry on their design, the kitchens were an essay in organisational and technical innovation. Writing in the Courier de l’Europe, the Vicomtesse de Malleville proclaimed: ‘There is more to be learned [in the Reform Club] than in the ruins of the Coliseum [sic], of the Parthenon, or of Memphis.’

While visitors would have marvelled at the magnificent gas ranges, revolutionary in an era of coal-fired cooking, and been enchanted by samples of fragrant mulligatawny, they might have been surprised to find framed pictures among the pies and hanging game in the larder and to hear the great chef pronounce the virtues of their painter, Emma Soyer.

Alexis and Emma had married in 1837. Alexis was from a humble background in Meaux-en-Brie, of the eponymous cheese, and, after working as a chef in Bourbon restoration France, had, following the July Revolution of 1830, moved to England and cooked in several grand households. London-born Emma Jones had been raised by her mother as something of a wunderkind: an accomplished musician and polyglot, trained in painting by the Flemish artist François Simonau (later her stepfather), she had first exhibited at the Royal Academy as a teenager. Quickly she gained an aristocratic following for her portraits, completing more than 100 by the time she was 15.

The couple had met in 1835 when Alexis approached Simonau for his portrait and was referred to his pupil. Alexis was smitten, composing effusive odes to his ‘Enfant gâté d’Apollon’. When Alexis sent tulips, Emma replied that she was ‘quite astonished at the liberty [Alexis] had taken […] and consequently, by the next mail, he will receive a box and his flowers back’. When the disheartened suitor opened the box, he found a still life of his tulips painted for him by Emma.

Simonau would not at first countenance a ‘mere cook’ marrying his stepdaughter and it was not until two years later, when Alexis was appointed chef at the Reform Club, that he relented. The wedding took place beneath William Kent’s Last Supper in the fashionable church of St George’s, Hanover Square, with Louis Eustache Ude, the doyen of French chefs in Britain, as witness.

Emma appears both to have pursued her career as a painter (exhibiting in London and Paris) and also to have helped her husband with his correspondence – while known for his wit, he struggled to write in English. Alexis, in turn, proudly promoted Emma’s work. Once, when Emma was unable to see him, she made a crayon drawing of herself on the kitchen wall by way of a calling card, which, lovingly glazed and framed by Alexis, became the latest of her works to be displayed in his kitchen-gallery.

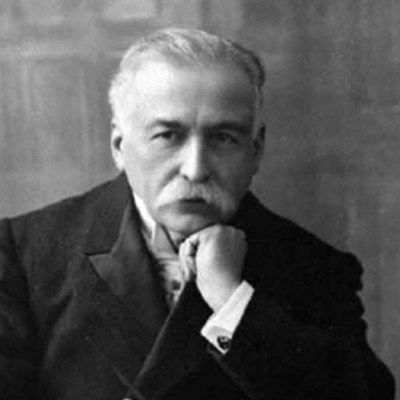

Alexis was thriving, as a chef and through an increasing number of commercial sidelines: legions of paying apprentices, the publication of a huge print of the club kitchen (Emma’s pictures visible in the larder), sauce bottles branded with his picture (based on a likeness by Emma), cookbooks, kitchen appliances and even steamship kitchen design. The Strangers’ Room at the Reform contains Emma’s portrait of Alexis at this happy time, described by the Observer as ‘an epicure balancing the leg of a dindon [sic] aux truffes on the point of his fork, and contemplating it with the delight which none but a finished French gourmet […] can feel in such matters’.

Sadly, Emma would die in premature labour in 1842. ‘No female artist has exceeded this lady as a colourist, and very few artists of the rougher sex have produced portraits so full of character, spirit and vigour’ extolled the Times in Emma’s obituary, likening her work to Murillo’s.

After her death, although banned by the Reform from using the larder to display art, Alexis would continue to celebrate Emma’s work, exhibiting 140 pieces at his Philanthropic Gallery in 1848 and in Soyer’s Symposium, his giant restaurant on the fringes of the Great Exhibition in 1851.

Of the 403 pictures Emma is recorded to have painted, only a handful are known to survive. Tate Britain displays a remarkable and delicate picture of two Caribbean girls holding a Bible, painted around 1831 at a time of intense campaigning for the abolition of slavery. Another work, Young Mariner and Dog (1833) – recently acquired by the Yale Center for British Art – demonstrates similar empathy, and was exhibited in the year the Factory Act banned child labour. Emma comes across as thoughtful, engaged and humane.

Alexis is also remembered for his benevolence. In between truffling ortolans (or ortolan-ing truffles, as he put it, given the diminutive size of the bird), he organised soup kitchens across London, travelled to Dublin to help relieve the famine (having tested a nutritious low-cost soup on club members), worked alongside Florence Nightingale to reform catering in British Army hospitals in Turkey and Crimea, and improved the diet of soldiers by inventing a campaign stove (which remained in use into the 1980s).

Amid the romantic tumble of Kensal Green Cemetery rises the Soyer tomb, confected by Alexis for his wife. Cherubs and a palette frame a marble portrait of Emma by Pieter Puyenbroeck, while Faith soars overhead. Below, giant bronze letters proclaim: TO HER. It is as much a monument to Emma the painter as an expression of Alexis’ engaging blend of uxoriousness, ambition and extravagance.

From the February 2026 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.