From the February 2026 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

At the Villa Malta in Rome last June, writers gathered from around the world to discuss the legacy of the late Pope Francis. One session addressed the crisis of faith as a theme in literature. What role, the speakers were asked, did religious belief play in contemporary writing? The British novelist Zadie Smith opened her response with discussion not of a novel, but of a work of art – a painting of the Crucifixion by Tracey Emin newly on display in London. Emin’s The Crucifixion had been reproduced in newspapers and praised by critics: if nowhere else, the question of faith loomed large over the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition. Emin provided Smith with an extravagant opening gambit – the one-time bad girl of British art going big on a devotional subject. From there Smith nimbly moved on to discuss liberalism, atheism and the preposterous notion that art might make you a better person.

To those engaged with her work, Emin’s choice of the Crucifixion is no great surprise – purportedly, she paints one every Easter. Beyond her exuberant persona, sharp tongue and carnivalesque subject matter (sex, intoxication), the overarching theme of her work has always been suffering. Why I Never Became a Dancer (1995) is about bullying and victim shaming; My Bed (1998) evokes the agony of heartbreak; The Abortion Waiting Room 1990 (2018) mourns both her own mother and the children she never had; in I watched Myself die and come alive (2023) she encounters the shadow of her own death and then painfully paints herself back to life.

In Smith’s concluding remarks she identified faith in a broader sense as something intrinsic to her work as a writer. ‘My liberal faith in the novel is a faith,’ she said, sincerely, to an audience of senior Catholics. It is a statement, I think, that Emin herself would understand at a deep, muscular level: the creative act as an act of faith and the pursuit of it as a form of devotion – particularly in relation to painting, a medium about which she suffered her own profound crisis of faith.

Emin dropped out of school at 13. Her passage into and through art college was facilitated to a tremendous degree by tutors who invested time and effort in supporting her. On the strength of her sketchbooks she gained a place at the Royal College of Art to pursue an MA in painting, despite never having worked in oils. In the summer break between her first and second years, Peter Allen, the school technician, and her painting tutor Alan Miller taught her how to stretch canvas and apply oil paint. Her mastery of the medium was followed by a dramatic crash after graduation: a pregnancy that made the smell of the oils nauseating and a traumatic abortion that pitched her into such depression that she stopped making art and retreated from the world. In 1990 Emin destroyed all of her paintings.

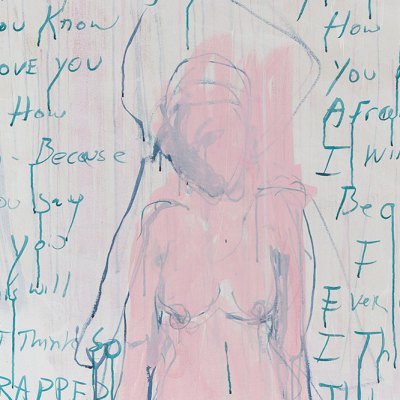

A few photographs give a sense of her work in this period, among them a striking unfinished Deposition from the Cross in which Christ appears both rising and falling, set against a modern British streetscape. Returning to art two years later, Emin ranged across media, creating appliquéd blankets, video works, assemblages and installations. As her star rose, she endeavoured to come to terms with her lost medium through the durational performance Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made (1996). A painting studio was built for her inside a gallery in Sweden. For three and a half weeks she occupied the space naked, available for public scrutiny through 16 peepholes installed in the exterior walls of the structure.

Documentation of the performance was later exhibited under the title Naked Photos – Life Model Goes Mad (1996), taking the emphasis away from painting and returning it to Emin’s body. The new title gave the performance a less personal aspect, placing it within the legacy of feminist actions asserting a woman’s right to be imagined as an artist, not just an artist’s model. The paintings Emin made during Exorcism… were considered part of the installation that emerged from the performance rather than works in their own right and yet there was nothing performative about their execution. In them she grappled with her guilt and anxiety around painting, and the influence of her Expressionist heroes Edvard Munch and Egon Schiele.

It was an unfashionable time to be a painter. Perhaps the only way for Emin to have approached the medium in that moment was as a performance. When she emerged from the exhibitionist isolation of her peep-show studio she again stepped away from painting. In hindsight, those loose, experimental paintings laid the foundation for her tentative return to the medium a decade later. It was a return as passionate as new love; since then, Emin has so fully re-established herself as a painter that it’s now a shock to recall the diversity of media in which she has worked over the course of her career. Surgery for cancer in 2020 left her unable to paint for a year. Ill health still often keeps her from the studio. Even as she contemplates her legacy, it would be reductive to see Emin’s turn to the subject of the Crucifixion as nothing more than a formal face-off with her art-historical fathers. There is something more heartfelt involved: thoughts about death, suffering, transcendence and the hard-won faith that is her faith in painting.

‘Tracey Emin: A Second Life’ is at Tate Modern from 27 February–31 August.

From the February 2026 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.