From the February 2026 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

When Erasmus of Rotterdam, the great Renaissance humanist, gave advice in his De copia (1512) on the techniques of evidentia – how to make writing vivid, ‘so that we seem to have painted the scene rather than described it, and the reader seems to have seen rather than read’ – his first example was the climax of a siege, a city ‘taken by storm’. Drawing on the Roman rhetorician Quintilian, he proceeds to a cascade of brutality: burning buildings, fleeing people, wailing babies, final embraces, plundering, looting, enslavement, mothers trying vainly to protect their children. Such heaped-up detail, Erasmus claims, makes graspable the reality conjured by the single word ‘siege’ or ‘sack’, an incomprehensibly chaotic experience taken at large. A kind of hectic excitement inhabits Erasmus’s list; and a disjunction of vivid representation and the pleasures it gives from historicity, legality and morality.

The different senses of ‘evidence’ – as vividness or as the juridical provision of proof of something not otherwise visible – make, Joseph Leo Koerner tells us, ‘a twisted thread’ running through the three ‘artists in the state of siege’, Hieronymus Bosch, Max Beckmann and William Kentridge, who are the subject of this rich and enigmatic book. Erasmus appears here not advising how to make a siege vivid, but as a paradigm for the humanist model of the production of works of art and their discussion as a badge of friendship. Koerner’s topic is the opposite: art in states of emergency, when enmity is taken as a fundamental state of human and political relation, and social and legal norms are suspended: in Reformation Europe, Weimar and Nazi Germany, apartheid South Africa. In such times, where discernment of friend and foe becomes, as Carl Schmitt claimed, the basis of politics, artworks can be treated as the enemy (by iconoclasts, for example), and as what Koerner calls ‘enemy images’: Trojan horses, which, admitted to the city of the mind, might take it by force. Koerner is here concerned with a question which already preoccupied him in Bosch and Breugel: From Enemy Painting to Everyday Life (2016): ‘What would art-historical analysis look like if its paradigm were not the greeting of a friend to a friend, but instead a mortal enemy slipping by unnoticed?’

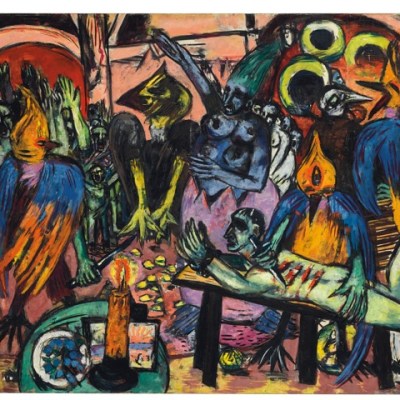

After a prologue on Aby Warburg, the book is organised as a triptych, offering substantial studies of Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights and its reception and of Kentridge, flanking a briefer essay on Beckmann. Triptychs – a form in which each of these artists works – allow both disjunction between their parts and parallelism and inversion to emerge. Each separate part is a satisfying study of the given artist and the relation of their works to states of emergency, exhibiting Koerner’s characteristic erudition and brilliance of formulation. Each also resonates with the others. The first part’s fascinating discussions of Wilhelm Fraenger trying out his wild theory of Bosch’s Garden as a ‘cult object’ for a secret sect of heretical free love in correspondence with Schmitt, and how this chimed with Schmitt’s theories of sovereignty and enmity, are recalled when Fraenger is discovered in the second section writing on Beckmann, while Beckmann’s writing and painting are read as un-Schmittian reflections on the Weimar Republic’s crises of sovereignty. The third part, meanwhile, finds Kentridge, who titled a silkscreen work ‘Art in a State of Siege’, experimenting with time, process and materials as he grapples with the European artistic inheritance in the South African states of emergency of the 1980s.

The apparent anachronism of placing Bosch with Beckmann with Kentridge is crucial to Koerner’s argument: in the ‘extreme state’, he asserts, ‘chronology becomes reversed, collaged, and avoided’. Sieges are at once the ‘extreme state of collective historical experience’ and commonplace; they ‘interrupt the flow of time’ and make disparate times and places ‘contemporaneous’. Each of the sections into which the parts of Koerner’s triptych are divided is headed by a time and a place. ‘Wit-tenberg, 1517’ rubs up against ‘Madrid, 2023’; ‘Munich, 1937’ against ‘Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2022’. All show the embroilment of art-making and art-history in the politics of extremity – including Koerner’s own autobiographical reflections, on the origins of his interest in Bosch, for example, in a copy of a German illustrated monograph pulled by his father from a collapsed building in post-war Berlin. This is a deliberately non-sequential art history, working by incongruous juxtaposition, and by the charge across time which animates art made and received in states of siege.

The book is thus not just a triptych, but also a mosaic, which Koerner calls ‘an idiosyncratic collage’. It includes siege itself; Carl Schmitt’s political theology; grisaille (especially where grey is unexpectedly lit by single points of colour, as in the closed cover of Bosch’s Garden, or the tip of the cigarette in Beckmann’s Self-Portrait, or the seed-spilling papaya in Kentridge’s Tropical Love Storm); suddenness; the idea of the Augenblick, the glance of an eye which is the German word for ‘moment’; Jewishness and antisemitism; and woods and trees, the first of which sometimes cannot be seen for the other in the book’s profusion.

This can be frustrating, but it also exemplifies something art history can do in a state of siege: hold its nerve. Forms of sometimes paranoid sense-making, collating vivid moments in an attempt to grasp a situation of arbitrariness and emergency, are both Koerner’s subject and his practice. This is a book which, though animated by topical urgency (what can art history be, and do, now, in a time of suspension of legal norms), refuses to relinquish its complexity. Just one passage explicitly registers a kinship between ‘apartheid South Africa in its final days’, Weimar Germany in the 1930s and ‘the presidency of Donald Trump’. Koerner cites Hitler in 1937 blasting ‘artworks that cannot be understood on their own’, condemning the work of interpretation, so often undertaken by Jewish art historians, as degenerate. Art in a State of Siege counterposes an art history of complexity and vividness, even in a state of siege.

Art in a State of Siege by Joseph Leo Koerner is published by Princeton University Press.

From the February 2026 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.