Canny collectors buy against the market but this can be a challenge if the work is totally at odds with the taste of the day. The highlight of a handsome group of fine and decorative arts from a Spanish private collection offered at Christie’s London on 7 December – an eclectic group ranging from a Hellenistic terracotta to a Botero bronze – could hardly be less fashionable. Bartolomé Esteban Murillo’s St Joseph and the Christ Child is, however, a wonderful piece of painting and an affecting image.

Murillo’s great gift was to endow his religious subjects with an entirely believable naturalism and a visionary otherworldliness. Here we are offered a moment of familial tenderness, as St Joseph gently takes the hand of the Christ Child to present him to the viewer. It is a gesture to be found across time and on every street and yet, of course, this is no ordinary child, as his golden halo and the glory of angels above bear witness. He may look upon us with an unflinching gaze, but it is one full of a heartrending sorrow.

St Joseph and the Christ Child (c. 1655–60), Bartolomé Esteban Murillo. Christie’s London (£3m–£5m)

There is something of the sweetness and palette of Barocci here, and it is striking that Joseph is not the usual old man but young, handsome and Christ-like. Prolific and popular in his day, Murillo remained highly prized among collectors across Europe well into the 18th century when this large altarpiece was among the paintings acquired in Spain by an English merchant and banker whose widow brought it home. It was in the Byng family collection at Wrotham Park from the early 19th century to 1990 when Christie’s London sold it for £2.4m, and it emerged again at Sotheby’s New York in 1998 to fetch $2.75m. Now it bears an estimate of £3m–£5m – not necessarily the kind of financial return auction houses care to boast about.

Murillo exerted a profound influence on 18th-century painters too, not least Greuze and Gainsborough. It is the likes of the Constable oil sketch offered at Christie’s Old Master and British Paintings evening sale on 8 December, however, which represent the other end of the spectrum of contemporary taste in this sale category. This little oil sketch on paper, Beaching a Boat, Brighton, is as free and fresh as one could hope, with Constable’s purple-brown primer still visible under the racing clouds and the painting’s near monochrome palette dextrously enhanced by a touch of brilliant yellow and of red, and bold gestural sweeps of creamy pigment.

Beaching a Boat, Brighton (1824), John Constable. Christie’s London (£500,000–£800,000)

This was one of a group of plein air sketches that the artist made while visiting his wife convalescing on the south coast in the summer of 1824. As he wrote to his friend John Fisher, all ‘were done in the lid of my box on my knees as usual’. This work is of particular note as he used it for his large studio sketch and final canvas of Chain Pier, Brighton, of 1826–27. It also bears a more colourful history than most. It had been given to Tate in 1986, but in 2013 the heirs of the great Hungarian Jewish collector Baron Hatvany claimed the painting. Hatvany had bought it in Paris in 1908 and deposited it with other works in a Budapest bank during the Allied bombing of the city, where it was seized either by the Nazis or by the Red Army. Despite new evidence coming to light of a deeply suspect 1946 export licence, the UK’s Spoliation Advisory Panel recommended restitution. The little sketch, laid on canvas, now bears an estimate of £500,000–£800,000.

An unpublished early 16th-century bronze statuette of a satyr steals the show at Sotheby’s London’s Old Master Sculpture & Works of Art sale on 6 December. Such small-scale bronzes are probably the most evocative manifestations of the poetic paganism of the Italian High Renaissance, treating as they do the mythical bestiary of monsters of the classical imagination – hydras, chimeras, tritons, and the like. Satyrs, male followers of Dionysus, god of wine, ritual madness, and fertility, are usually half-man and half-goat, depicted with furry thighs, hooves, pointed ears, and horns and, of course, a permanent erection. For the humanist scholars of the day, their duality manifesting the unbridled forces of human nature seemed to have particular appeal.

The master of the small classicising bronze in the great university city of Padua was Andrea Riccio, and this statuette is attributed to Desiderio da Firenze, a sculptor active in the city from 1532 to 1545, who may have worked with Riccio or inherited his models. (There is possibly no field of art-historical scholarship more contentious than Old Master bronzes.) This salacious but sadly emasculated satyr is one of the finest versions of a model known in a small number of casts and variants, and appears to lunge forward as if cradling something in his arms – perhaps a missing satyress. Estimate £150,000–£250,000.

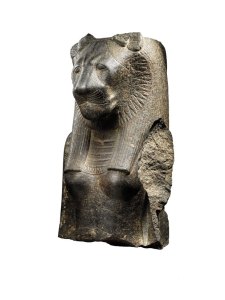

Bust of the goddess Sekhmet, Egyptian (18th Dynasty, reign of Amenhotep III: 1386–49 BC). Courtesy Sotheby’s

While the satyr reflects a growing taste for small-scale bronzes for the private collector, the diorite bust of the lion-headed goddess Sekhmet from an enthroned, full-length figure reveals the Egyptian taste for the public and monumental. Both, coincidentally, were associated with feasts of great intoxication. This Sekhmet was probably among the 600 or so images of the goddess of war and protector of the king that lined the courts of the great Temple of Mut, built largely by Amenhotep III at Thebes around 1400 BC. Most of the surviving figures have long been dispersed among the great museums of the world, but we have seen a few on the market recently. A damaged but full-length example that once belonged to John Lennon sold at Sotheby’s New York last year for just over $4m. This bust, from the collection of the late surrealist poet Joyce Mansour and her husband Samir, comes to the same saleroom on 15 December with an estimate of $3m–$5m.

Also on 15 December is the highly anticipated dispersal of Madeleine Meunier’s estate through Christie’s Paris in association with Millon. Meunier was married to the legendary dealer Charles Ratton and, previously, Aristide Courtois, a French colonial administrator in the Congo who brought hundreds of tribal objects to France. The highlight of the sale is the pre-contact Luba-Shankadi headrest attributed to the Master of the Cascade Coiffure, active in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo in the 19th century. Such headrests were conceived to protect the sleeper’s elaborate hairstyle (estimate €500,000–€800,000). On offer are some 80 items of African and Oceanic art, as well as 60 antiquities.

From the December issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.