The building that houses the Zabludowicz Collection in north London is a local heritage landmark: a Grade II-listed 19th-century Methodist chapel in the neoclassical style, its façade complete with Corinthian columns, carved wreath-adorned pediment, tall round-arched entrance and stained glass windows. Inside, however, the focus is very much on the present – and the future. This January, the centre for contemporary art opened the first dedicated space in the UK for exhibiting works made using virtual reality (VR) technology.

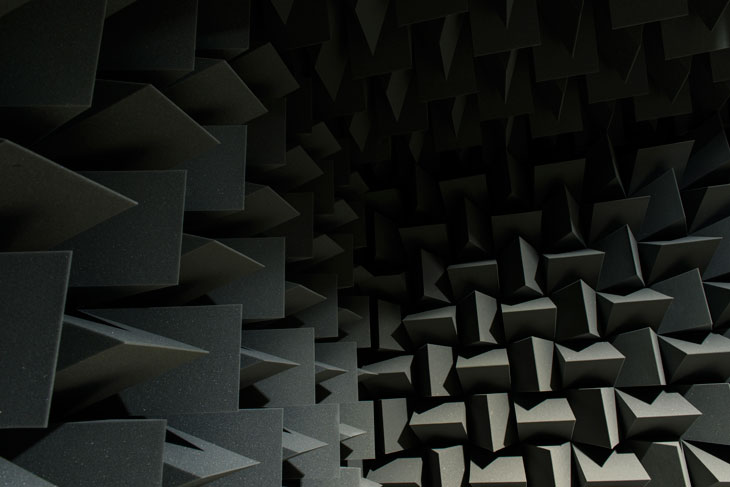

Located at the back of the building, on its upper level, the 360: VR Room is just that – a tiny room. The only object inside is a VR headset, its cord dangling from the ceiling. The room’s other notable feature is a mosaic of triangular prisms, made out of black foam, that lines its four walls: the vestiges of an installation by Haroon Mirza for his recent exhibition, designed to create an ‘anechoic chamber’ that shuts out all sound and light (and potentially triggers a hallucinatory state for the sensory-deprived visitor). It’s a fitting environment for an experience intended to transport its users somewhere else entirely, to a different – virtual – reality.

360: VR Room, installation view, Zabludowicz Collection, London. Photo: Elliot Sheppard. Courtesy Zabludowicz Collection, London

The artwork chosen to inaugurate the space is a piece from the Zabludowicz Collection (there are, at the most recent count, seven VR works in the collection) by American artist Rachel Rossin. The work, titled I Came and Went as a Ghost Hand (Cycle 2), was made in 2015 during Rossin’s fellowship in virtual reality research and development at the New Museum in New York. Donning the VR headset, viewers find themselves in a strange world that is impossible to mistake for the real.

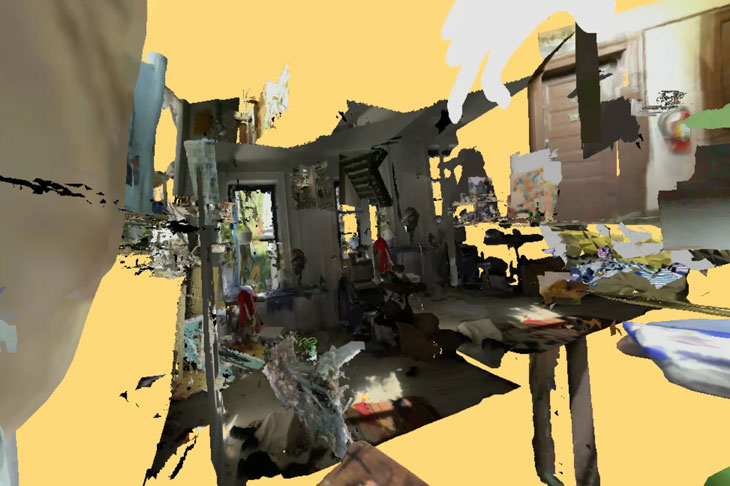

A pale yellow background, stretching in all directions, provides the depthless surface for a constantly moving arrangement of multi-coloured forms, ranging from the clearly identifiable (a staircase, a doorway, a female figure sitting cross-legged, a crawling outline of a hand) to pixellated abstractions. Turning their head or taking a step forward, the viewer can explore the space – but, like a ghost, will find it impossible to make any contact with their surroundings: effortlessly penetrating brick walls; unidentified flying objects soaring as if right through them. (Until, that is, they step a little too far and end up gently colliding with the thankfully soft edges of the foam-lined chamber.) Over time, a clearer sense of location emerges in this VR world. Rossin has created a modern-day portrait of the artist’s studio. A work table, stacked canvases, the artist at her easel (and laptop): these are all objects and scenes captured using 3D scans in her own studio space in New York, where Rossin makes both her digital works and oil paintings on canvas.

I Came And Went As A Ghost Hand (Cycle 2) (2015), Rachel Rossin. Installation view, Zieher Smith & Horton, New York, 2015.

The fragmented, at times abstract, nature of the VR rendering is no accident: Rossin has purposefully taken the scans of her studio and altered them, pulled them apart. This is because, as is perhaps the case for any good artist, Rossin’s use of VR technology is driven by a fascination with and desire to explore the medium itself – to test its limits and potentials, to find its capacities for communicating ideas and experiences through its specific mode of representation. For Rossin, ‘inevitably it’s a metaphor for entropy’, the process by which digital data is compressed, distorted or lost over time holding up a mirror to the very nature of representation as loss, as the death of the real.

There are, of course, fundamental differences between the immaterial, insulated nature of VR experiences and the way we encounter physical objects, whether paintings, sculptures, or moving-image works viewed on a monitor or projected onto a wall. But some of these differences, such as the fact that currently no more than one user can occupy and interact with the VR world at a time, may not exist for much longer. This is just one example of the rapid pace of technological advances in the field of VR, in which a work from 2015 could soon be considered archaic. And it’s why the Zabludowicz Collection’s current plans, not just to exhibit VR works from their collection but also to collaborate with other institutions such as the New Museum on conferences and the commissioning of new works, are to be welcomed. As artists continue to find interesting ways to make, break and expand the possibilities of virtual reality worlds, so too should institutions remain engaged with the collection, conservation and display of the technology.

‘360: Rachel Rossin’ is at the Zabludowicz Collection, London, until 18 March.