‘Look but don’t touch’ is one of those commands that can be applied to the art gallery as well as sexual relations. In each case, there is frustration but also frisson. What happens when what is within reach is off limits? What kind of sensation, even pleasure, arises from the denial?

In ‘Abstract Erotic’ at the Courtauld, the sculptures are practically begging for human contact. It’s a small show: two rooms, three artists. In 1966, the same artists were included in ‘Eccentric Abstraction’, an exhibition curated by the writer and activist Lucy Lippard at the Fischbach Gallery in New York. Louise Bourgeois, Alice Adams and Eva Hesse were not close – they knew each other through Lippard but moved in different circles – yet they shared an interest in found and scavenged materials, weird physical forms, clashing textures and the nubbly, crusty, viscous properties of liquid latex.

As Lippard wrote in an accompanying essay republished in Art International, her show involved an attempt to locate work that ‘provoke[s] that part of the brain which, activated by the eye, experiences the strongest physical sensations’. It prioritised pieces that, ‘even if they are not supposed to be touched […] evoke a sensuous response’. (This part is quoted in the opening wall text that greets visitors to the Courtauld exhibition.) These works both departed from and responded to the clean-lined, modular minimalism that dominated in the 1960s. They were similarly interested in paring things back to the essentials, but often to fleshier, messier ends.

The pieces on show here deal with the erotic in elliptical ways. Abstraction, so Lippard’s original argument went, far surpassed figuration in its capacity to explore the delicacy and imaginative possibilities of the erotic domain: ‘more hard-edge than hard-on’. This idea is given fuller reign in ‘Abstract Erotic’, where those edges are sometimes hard and sometimes frayed, often tightly bound but also bubbling up or spilling over, as though the objects on display cannot hold themselves in. This is not straightforwardly sexy or explicit curation but an open-minded probing of the complications and co-mingling of desire, disgust, power exchange, touch and so on.

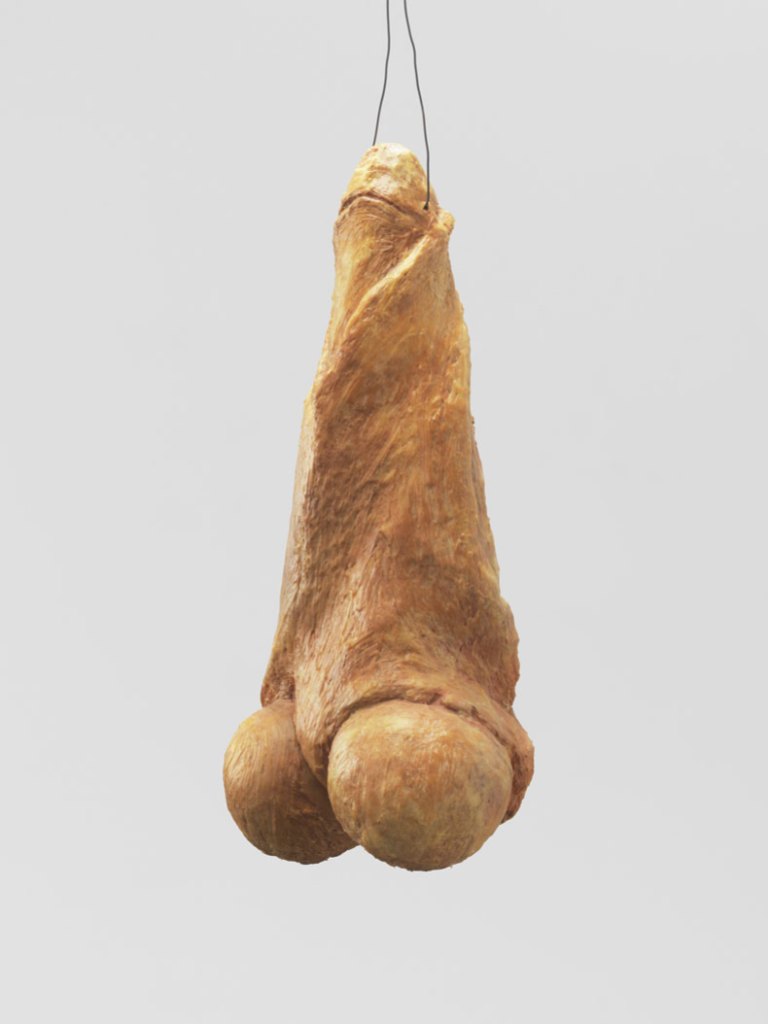

There is only one obvious hard-on. Louise Bourgeois’s Fillette (Sweeter Version) (1968–99; cast 2006) hangs in the first room: a urethane rubber cock and balls. The title means ‘little girl’ in French and its mix of the explicit, the witty and the emasculated offers a typical Bourgeois-style bodily topsy-turviness. It can be read as a partner piece of sorts to the labial Le Regard (1963) next door, a squat, undulating piece in latex over fabric tilted to reveal its inner folds. In The Sadeian Woman (1978), Angela Carter described pornography’s ‘abstraction of human intercourse in which the self is reduced to its formal elements’ – an arena where, crudely, man is ‘positive, an exclamation mark’ and woman is negative, an ‘inert space, like a mouth waiting to be filled’. Bourgeois takes these same formal elements and shakes them up, embarking on a series of exaggerations and inversions. Breasts multiply. Orifices are not passively yielding but at once confronting and inviting (a photo of Fillette taken by Peter Moore just after it was made shows it still glistening with liquid latex). The dick dangles from a hook, or, as in the famous Robert Mapplethorpe photo, is carried jauntily under one arm.

Elsewhere, Alice Adams’s work relies on what she described in 1969 as a series of ‘tensions and compressions’. The American artist’s move away from making woven textile pieces to using chicken wire, steel cabling and other industrial materials found on the streets yield a series of dense, suggestive sculptures. Big Aluminium 2 (1965; partially remade 2023) is a variation on a sculpture first shown in Lippard’s exhibition. In its original form, it comprises a smaller chain-link fence sculpture half-penetrated and half-nestled inside the larger one, creating a blunt, almost gawky effect. Here it looks more like a vast, disembodied limb. In Expanded Cylinder (1970), the chain links instead form an absent presence: impressed into foam, the grid of indents are then set solid with latex. Its bulging, gridded shape becomes more pleasing the closer you lean in, as the surface undulates with little creases and ripples.

Eva Hesse’s work is perhaps the most tantalising. So much of it is pendulous, particularly a series of works that involve lumpen forms suspended from cord (as well as pieces such as Addendum (1967), in which cords dangle like thin streams of milk from a long line of breast-like papier-mâché shapes). All three artists display a sly sense of humour, but Hesse seems to revel in absurdity the most. In an essay in the accompanying catalogue, Briony Fer identifies a quality of slapstick, a confounding of category in which ‘what [Hesse] makes can be caught in the act of escape […] or otherwise making some sort of getaway from what we might expect of it.’ In Untitled or Not Yet (1966) a cluster of unidentifiable, weighted shapes wrapped in polythene are suspended in netting and the shiny, almost gauzy plastic strains against their containers. A photograph of Hesse from the same period shows her posing with either this work or one similar, her face framed by these polyps, like some kind of grotesque growth or hat.

The audience may not be allowed to run their fingers over the surfaces of these works to feel the cold bite of metal or rough texture of cord, but it’s impossible not to be aware of the hands that have shaped them into being. Chain links have been loosened and rewoven, enamel shapes netted and suspended, balloons blown up and encased in papier mâché, and liquid latex has been carefully poured to create a second skin. The artists have imprinted themselves on their works. Sometimes, as with Louise Bourgeois’s Avenza sculpture of 1968–69, they even wore them. Lippard wrote that ‘body ego can be experienced two ways: first through appeal, the desire to caress, to be caught up in the feel and rhythms of a work; second, through repulsion, the immediate reaction against certain forms and surfaces which take longer to comprehend.’ ‘Abstract Erotic’ stages a lively and often curious dialogue with Lippard’s earlier writing and curating, but in narrowing its focus to these three women, it also starts a new conversation and brings welcome attention, particularly, to Hesse and Adams: their work, their thinking and their methods of making. Many of these pieces here invite both states Lippard identified – they are by turns tempting and repulsive – and the cumulative effect is a taut, teasing and troubling exhibition.

‘Abstract Erotic: Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Alice Adams’ is at the Courtauld Gallery, London, until 14 September.