From the June 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

On 2 November 1918, with the war nearing its conclusion and the German Empire close to collapse, the art historian Aby Warburg was pacing his home in Hamburg, gun in hand, threatening to kill his wife and children. Although his doctors blamed the disastrous political situation, Warburg for many years had been battling with chronic anxiety, first diagnosed as ‘neurasthenia’ and later schizophrenia. For the next six years he would be treated for psychosis in various hospitals and asylums. His case was considered hopeless, yet Warburg did recover.

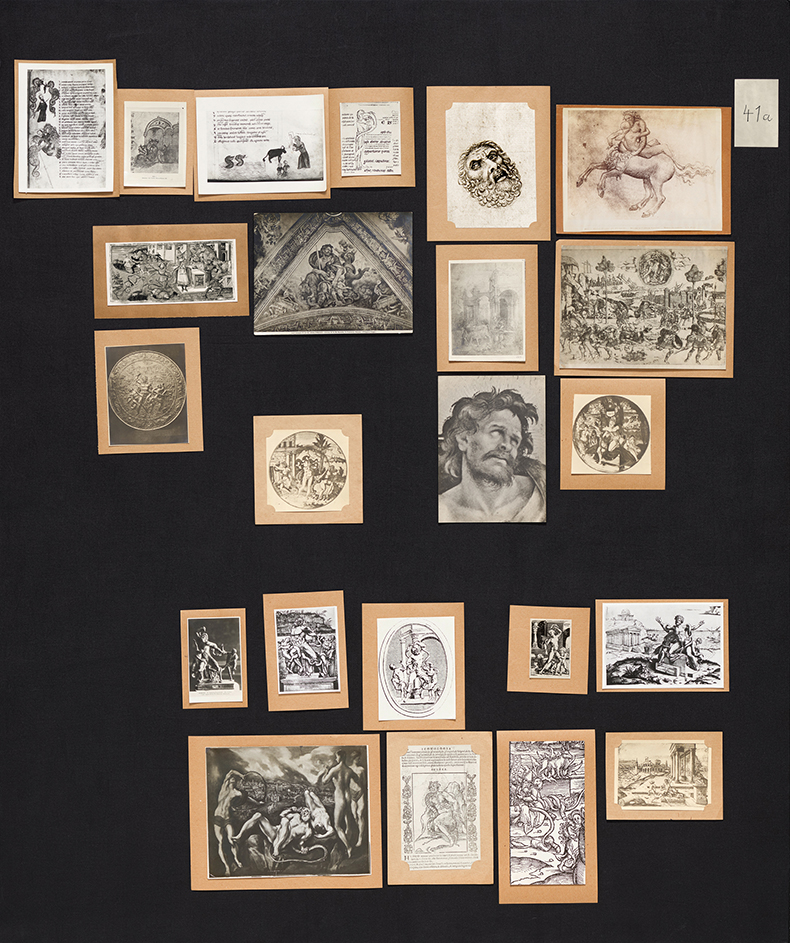

The eldest son of a powerful banking family, he rejected that path, instead choosing to pursue an academic career. He studied at universities in Bonn, Munich and Strasbourg, and amassed an internationally significant collection of rare books. After returning home in 1924, he went back to work as director of his library – the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg – and embarked on one of the most original art historical projects of the 20th century: the Bilderatlas Mnemosyne. Comprised of photographs attached to large wooden panels, the atlas connected artworks with similar poses and gestures across time and space. With each panel organised around a theme, viewers could trace the afterlife of antiquity through specific motifs repeated by later artists.

It has been more than 50 years since Ernst Gombrich’s ‘intellectual biography’ of Warburg was published, and Hans C. Hönes’s Tangled Paths is a necessary, serious and intellectually provocative contribution to our understanding of a man whose work has only increased in influence since the turn of the century. In 1999 the Getty Research Institute produced a translation of Warburg’s collected writings (first published in 1932, three years after his death). The greater availability of his work, combined with influential studies such as Georges Didi-Huberman’s L’image survivante (2002), led to a renewal of interest in the scholar and a wave of research focused on alternatives to organising art history according to linear chronology.

Hönes’s book concentrates on placing Warburg’s life and work in the intellectual context of the late 19th century and the professional networks of the early 20th. Interestingly, this means that he characterises Warburg as a ‘minor figure’, marginal to the main debates in the rapidly evolving discipline of art history. Warburg’s own legacy was sustained principally through his library, transferred from Hamburg to London in 1933 to escape Nazi Germany, and surviving as the Warburg Institute. Its building in Bloomsbury will complete a major two-year renovation this summer, meaning Hönes’s book appears at an appropriate moment.

For Warburg, research was a therapeutic tool, swinging between theoretical speculation and intense empirical investigation. His doctoral thesis, published in 1893, rejected aesthetic criticism and the contemporary cult of Botticelli. Instead, he regarded the artist as merely a ‘pliable’ and ‘unthinking’ conductor of literary sources and classical motifs. In Warburg’s analysis, form is discussed only when it is ‘iconographically remarkable’, and what appeared noteworthy in the Primavera or Birth of Venus were ‘accessories such as locks of hair or billowing drapery’, the ‘intensification of outward movement’ being the true sign of antique influence. While travelling in the south-western United States in 1895 and 1896, Warburg began developing theories of symbolism and witnessed Native American ritual dances. These ideas and experiences would re-emerge many years later in a lecture he delivered while a psychiatric patient at Bellevue Sanatorium in Kreuzlingen. In October 1897, Warburg and his wife Mary moved to Florence, where he would continue his archival research, resulting in some of his best known articles such as that based on his discovery of the will of the banker Francesco Sassetti.

Warburg repeatedly turned down professional opportunities at a range of universities, revealing in the process his deep insecurities and fear of public scrutiny. He did maintain a close relationship with the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz (founded in 1897), and was a member of the organising committee for the biennial International Congress for Art History, being instrumental in taking the tenth congress to Rome in 1912. It was here that Warburg delivered his lecture on the ‘iconology’ of the frescoes in the Palazzo Schifanoia at Ferrara. Yet only within the context of his own library could Warburg’s ideas be fully developed. These were realised in his multidimensional Bilderatlas, the images of which, Warburg believed, illustrated our ‘attempt to absorb pre-coined expressive values by means of the representation of life in motion’.

Panel 41a of Aby Warburg’s Bilderatlas Mnemosyne (reconstruction of 2020). Photo: Wootton/fluid

Warburg was given to repeated autobiographical reflection, what Hönes calls ‘a constant wish to join the dots of his life, and to evoke a logical coherence in a life and career’, and the current book does much to clarify the scholar’s somewhat tortured intellectual journey. Emerging at points also is the personality of Warburg himself, in all its grandiosity, arrogance, snobbery, and self-pitying delusion. Hönes does not dwell excessively on his personal life, making fleeting reference to Warburg’s fraught relationship with his brothers, his feelings of resentment towards his wife and children, his affairs and domestic violence. Nor does the book contain many lengthy quotations, the author preferring paraphrase and summary, meaning the reader is kept at arms-length from the sources themselves and especially the complexity of Warburg’s literary style. The content of his letters and diaries is only ever half-glimpsed, which can be occasionally frustrating.

Warburg, we are told, placed great ethical importance on the work of the historian, insisting that the ‘voices from the past’ should speak for themselves and perform their own Eigenbeleuchtung, or self-illumination. Hönes takes a different approach, and it may be that another biography of Warburg is needed in future, one more sensitive and receptive to the emotional and psychological life of its subject, to reveal this aspect of the man himself.

Tangled Paths: A Life of Aby Warburg by Hans C. Hönes is published by Reaktion.

From the June 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.