In ‘Frieze Frame: How Poets, Painters, and their Friends Framed the Debate Around Elgin and the Marbles of the Parthenon’ (Paul Dry Books), the poet A.E. Stallings tells the story of how Lord Elgin removed the sculptures from the Acropolis of Athens and considers how they have fared in London ever since. Stallings captures both the intense excitement the marbles caused in artistic and literary circles in England and also the sense of loss the site of the Parthenon represented for Greek writers of the 19th and 20th centuries. In placing imaginative responses to the marbles above arguments based on property rights, Stallings makes a powerful case for giving these masterpieces from 5th-century Athens a much-needed new lease of cultural life.

Fatema Ahmed: This book began as an article, or a series of articles, in the Hudson Review. What did you set out to write?

Fatema Ahmed: This book began as an article, or a series of articles, in the Hudson Review. What did you set out to write?

A.E. Stallings: I call this my accidental book. I had no intention of writing it. During the Covid lockdowns, which were very strict in Greece, I thought, I’ll do a very quick blog post about Byron and Keats, Cavafy and the marbles. It kept growing and I kept falling down various rabbit holes and finding out new and strange things that I didn’t know.

In the introduction you mention being ‘vexed’ by how some classicists write about the marbles, going from ancient Greece to now, as if there is no Greek history in between.

One of the triggers was social media. I felt there was a strange entitlement of classicists swooping in and not being bothered to find out why the marbles are where they are and how that happened: going straight from Periclean Athens to the British Museum and the Acropolis Museum and saying, well, Elgin got them legally or illegally. But it turns out none of that is straightforward.

The book starts with reactions to the marbles when they arrived in London. Everyone knows Keats’s sonnet about reading Chapman’s translation of Homer, but his sonnet about seeing the marbles is not as well known. (And perhaps it’s fair to say that it’s not as good?)

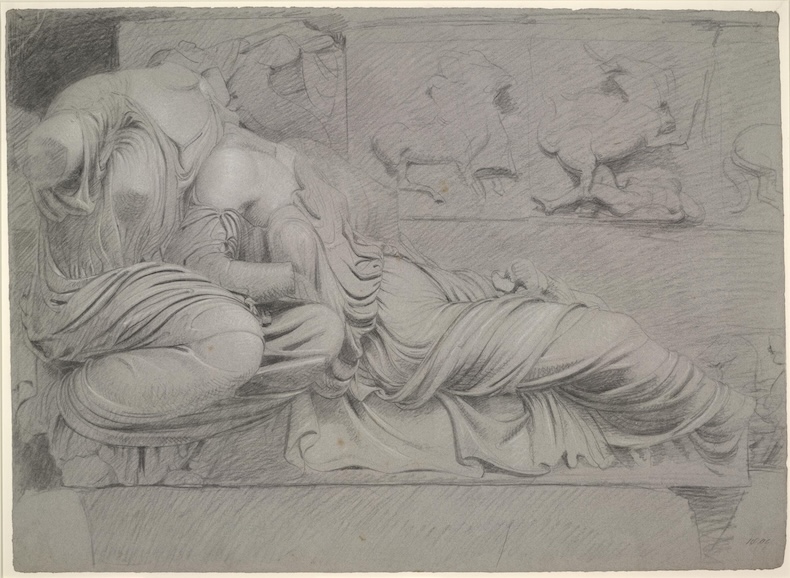

I’m interested in what prompts or triggers poems – the moment that they’re marking. The marbles had only very recently been put on display in the British Museum to the public. It was a huge event. They had been for a while in London in a kind of makeshift shed on Park Lane. I love the idea of Keats going to see them with his friend Benjamin Robert Haydon, who was a painter […] [with] this very engaging and lively autobiography, which gives us glimpses into… it’s like Bridgerton London. He is so excited about the marbles and he’s showing Keats what he sees. So it’s not just Keats having an unmediated experience in a cool museum. [The marbles are] completely new. He’s being carried along by this enthusiasm and the poem is, in part, about being overwhelmed by Hayden as much as anything else. I think that’s one of the reasons why the poem is so blurry and sublime. We’re not really sure what we’re seeing in the poem, but it’s about being carried along.

Pair of incomplete figures at the northern end of the east pediment of the Parthenon Marbles, with metopes in the background (1809), Benjamin Robert Haydon. British Museum, London. Photo: © The Trustees of the British Museum, shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence.

Byron is a singular figure in a number of ways. He travelled a lot, but he wasn’t a collector. He was very interested in Greece, but he was unsentimental about the marbles. Can you say something about his imaginative response to them?

By the time Byron gets to Greece, all of this has already happened: the marbles have been removed and there have been shipwrecks and so forth. He sees the temple for the first time already denuded of these ornaments and excavated in the rubble. But he has encountered the marbles before he leaves England. It’s in this again, very Bridgerton shed with scantily clothed boxers and, you know, nude statues and Regency bucks walking around.

He has witnessed the sculptures, but he doesn’t have this collector’s avidity – pretty much every traveller to Greece or Turkey was picking up whatever was not nailed down if they could get hold of it. Even people who loudly decried what happened to the Parthenon were themselves picking up bits of sculpture every which way they could. Elgin’s original plan was to decorate his house with the marbles. [Byron] is simply not interested in that at all. He’s interested in ruins being where they are and that’s part of this Romantic experience of the landscape, but he’s not interested in having sculptures decorate his house.

There’s an argument to be made that he ruined Elgin’s life. They never met. When he goes on this rant about Elgin taking the marbles off the temple in Childe Harold, he does send a missive because he’s a gentleman: look, I just want you to know that I’m publishing something and your name is in it and you should hear it from me. Elgin’s secretary is like, don’t worry about it, any publicity is good publicity. Then Childe Harold blows up and becomes the most famous poem just about ever, and suddenly Elgin was a looter. This was very shocking to Elgin and, to a certain extent, he never really recovered from these accusations.

You liken the Parliamentary report looking into the purchase of the marbles to ‘Platonic dialogues on the nature of art, value and authenticity’. What do you mean by this?

They are asking sculptors and artists as well as politicians, basically, are these any good? It’s such a given to us now that these are among the greatest works […] that to see them in this fresh light of, are they as good as the Farnese [sculptures], these statues that we now automatically dismiss as less good. They were looking to a certain extent with very fresh eyes at this. I’m intrigued by the fact that [they say that] they’re priceless, but we have to put a price on them. What is their purpose here? There’s an idea that they’re going to form this school of art to improve British art and that there’s something ultimately altruistic about bringing them. I was really intrigued by these abstract concepts being hammered out in a government situation. It seemed surprising.

The committee also writes about offering the sculptures ‘asylum’, but there’s still a sense that the sculptures should offer something in return.

I was very interested in the way they’re almost treated and often spoken of as visitors or as things with their own agency. One of the strange things about humanoid sculptures especially, but maybe also equids, is that they somehow have their own being.

Greek poets, as you would expect, focus more on the moment of destruction – which is not Elgin’s activities, but the Venetians blowing up the Acropolis in 1687 – and also on the site being deprived of its friezes.

I’m not an expert, but it does seem that Greek poets generally are more concerned with the larger destruction by the Venetians. Elgin is someone who comes later and is adding insult to injury. The Acropolis is fairly whole up until that moment, it’s fairly unscathed and would be unscathed today, possibly. Then in 1687 there’s a battle and the Turks were using the Parthenon as a powder magazine. But people do forget also that the rock of the Acropolis was a military fort, in ancient times and in relatively recent times. It is the high point of the city that you have to seize.

For the Greek poets, Elgin, the debate with Keats and Byron and where the marbles belong is a lesser concern than this horrific moment of full-on destruction. There’s also a fascination with it: avant-garde poets fantasise about that moment, so there’s a flip side where it’s a blowing up of the classical past that may be a way forward. But with the marbles you do have poets – George Seferis particularly, who was the ambassador to London – visiting the marbles and having this seasick sense of exile and melancholy to see them in London. They’re less concerned about Elgin’s actions and it’s more about exile and the fate of the Greek state.

One of the most interesting poems you discuss is by the American poet James Merrill, who lived in Athens for a decade. ‘Losing the Marbles’ is a hard poem to describe, because it does so many things, but can you try?

It’s a poem in several parts and it maybe looks back to his time in Athens, but it’s written at a later point where he’s grappling with the AIDS epidemic and his own mortality. There’s a joke, which comes up a lot with Elgin, about losing your marbles, and Merrill embraces that joke about losing memory. When he was living in Athens, he was seeing the Acropolis on maybe a daily basis. He hasn’t fetishised this idea that the marbles must always be preserved intact or without the weathering of time. He embraces their mortality – what if they had been left up there and they did erode with acid rain? I think he does come at it from a different perspective, neither English nor Greek.

In your description of the campaign of Melina Mercouri, the Greek culture minister, to get the marbles back, so much of the British coverage of her, which you quote, was incredibly dismissive. You compare her to Byron in terms of her influence on how we see the marbles. Can you say more about that?

They’re both very polarising figures and there is this sense that they push the arguments to extremes, whether it’s Byron talking about pillaging and looting and so forth, and then Mercouri… they’re both charismatic figures that I think perhaps the British imagination is somewhat diffident about and somewhat unsure about the charisma of their arguments and maybe that emotional thing. With Mercouri, you just read all of the stuff about her visits and from our perspective, at this distance, it’s very clear that it’s extremely misogynistic and condescending, but it still surprises me.

You mentioned that James Merrill might have seen the Acropolis every day, but one of the details I like most in the book is that you’ve spent a lot of time looking at copies of the northern and western Parthenon friezes at the Acropolis Metro station.

Yes, they’re lovely horses. I think I’ve noticed more details waiting for trains than I have in museums or in art books. Just that lovely notion of these modern metro trains zipping past them. They’re always getting prepared for whatever procession it is that they’re getting prepared for. My favourite is one before they’ve got him tacked up – I guess it could be after, but I think it’s before – where he’s rubbing his muzzle on his hoof, which, if you have any experience with horses, is something that you see all the time. It’s just a wonderful observed detail and you do also have these anatomical details of the veins on the bellies, and so forth. But I just like that the horses are behaving very horsey.

One of the six caryatids of the Erechtheion Temple on the Acropolis. British Museum, London. Photo: © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence.

We should get on to where some of the marbles actually are, which is in the British Museum. I like your account of trying to see the caryatid from the Erechtheion on Google Street View, when you were unable to visit.

That room is often shut. It’s really frustrating. I’ve been to the museum numerous times and it’s regularly not on display. When I first saw the marbles I think the caryatid was closer, but she’s been separated. She’s subjected, I think, to demonstrations and protests as well. She’s been shunted aside and there was such a big deal made to get her. It’s fascinating that you can use Google Street View and you can look around her a little bit and zoom in. Something I did a lot during Covid was look at things through the British Museum site.

The museum website is also fascinating in the way it words things and Elgin’s name has kind of been scrubbed from the whole business. By the end of the book, I actually felt sorry for Elgin. He lost his marriage and his nose and his fortune and had at least tried to keep the collection together and hadn’t sold it to Napoleon, and he dies in disgrace and bankruptcy.

I also felt sorry for his agent, Giovanni Battista Lusieri, who was responsible for removing the friezes and might be much better known as an artist in his own right if he hadn’t spent years working for Elgin.

He’s splendid. I’ve only seen a catalogue from an exhibition and very few of his works in person, but the few that I have seen are gorgeous. And Byron thought he was a very good artist. A huge number of his watercolours were destroyed in a shipwreck and he was very distracted by the removal and excavation project that he ends up on for Elgin. One of the strange paths and coincidences of the marbles is that the painter Elgin originally wanted was Turner. And you just think, well, that would have been different for everyone involved. Maybe he would have been more interested in drawing things in situ and not taking them down.

When you start to discuss the idea that it’s time for the marbles to have a new lease of life, one of the key elements in this argument is the new Acropolis Museum. The form of the building feels like an appeal: it’s architecture that speaks – and what it’s saying is that it wants the marbles back from the British Museum. Can you describe how it was received in Athens?

I remember when the new Acropolis Museum opened [in 2009] and it was quite controversial for a while because it is a rather striking modern building among some older neoclassical buildings. It’s one of those things like the Eiffel Tower that started off as quite controversial but is now almost unanimously liked and appreciated in Athens. I remember the old Acropolis Museum, where they weren’t even able to show the marbles that they did have at that time. [The new museum] is a marvellous space. It does lead you to this overwhelming question or idea. You go through all of the different levels and end up in this beautiful space which is exactly aligned with the Parthenon.

It has the frieze plus plaster copies of bits that it doesn’t have are portrayed the right way round, whereas the British Museum’s friezes face inwards. So you can walk around them as they were meant to be experienced, although they’re not as high up as they would have been on the building itself. One of the things that really struck me is how purpose-built the Parthenon is to its space, out of local stone. We tend to think of it as universal, but for Athens it was really the centre of a kind of locality.

Five caryatids of the Erechtheion at the Acropolis Museum in Athens with an empty plinth for the absent sixth. Photo: Kaveh Kazemi/Getty Images

You’ve also imagined what a future Duveen Gallery could contain when the marbles are not there any more. What would you fill it with?

I don’t know what the future of the Duveen Gallery is as my understanding now is that there is talk of revamping the whole Greek and Roman display and that might involve tearing down the Duveen Gallery. But, for me, the Duveen Gallery is also a historical space. It’s been there for a good period of time, close on 100 years. It was also designed to be exactly the proportions of the Parthenon. You’ve also got a century of people, of artists and writers experiencing the marbles in that space that originally had hugely expensive grey silk wallpaper. It would be a wonderful transition to make it about the history of the marbles and the British Museum, which I think has become a story unto itself. The museum has tended to avoid that narrative but it would be fantastic, for instance, to have some of the original Lusieri paintings, the Dodwell etchings. It owns some of Haydon’s drawings.

You could have some of the Elgin stuff that’s not on display, because when people originally went to go see Elgin’s collection, it was not just the marbles. There is a very rare lyre that is actually on display somewhere in the museum. There is a giant Egyptian beetle. There are altars Elgin took from Delos that have never been on display and are just mouldering in the basement.

You could have some of the original plaster casts of the marbles, which are important in their own right because they were made before the cleanings [in the late 1930s]. There’s a move afoot to have exact marble copies made. I like what some museums have done with lights to show the polychrome aspect of the marbles where you can see how richly coloured they were. That would be exciting and people would flock to the museum to see that, to see things literally in a new light.

What surprised or delighted you when you were scouring literature and art for references to the marbles?

Once I started going down the various rabbit holes, I started to notice mentions of the marbles more. One of the things I came away with was how the marbles and the controversies around the marbles touched on absolutely everything in the 19th century. I kept running into that. I was reading Billy Budd – and Melville has a poem about the marbles – but there’s a section in the novella where Billy Budd’s anatomy is specifically described in terms that Hayden would notice and approve of. I also came across it when I was reading Willa Cather. I didn’t know the work of Felicia Hemans very well and suddenly realised that the prominent female poet of the time writes about them.

It appears more in novels than in poems, to be honest. You could do an anthology of scenes where people meet up in front of the marbles. (It’s in movies as well.) I became interested in the tentacles by which the marbles connected to almost everything. You could do a whole college course on the long 19th-century through the marbles.

Frieze Frame: How Poets, Painters, and their Friends Framed the Debate Around Elgin and the Marbles of the Parthenon by A.E. Stallings is published by Paul Dry Books.

[Lead image: shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence]