From the January 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

With her signature bowl cut and petite silhouette, Agnès Varda, who died in 2019 at the age of 90, was a fixture of the French cinema landscape for more than half a century. She famously lived in a pink-painted house on a cobbled street in the 14th arrondissement of Paris and was celebrated as a beloved oddball. But she was also recognised as a pioneering female director and highly original artist who excelled in a form of docu-fiction that seamlessly weaves together the real and imaginary. This year has marked a significant stage in her canonisation: Laure Adler has written the first major biography of Varda; two events at Arles over the summer presented her still photographs; and her work is on show at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles until January 2025. Finally, ‘Viva Varda!’ opened in autumn and is at the Cinémathèque française until the end of January.

We begin with photographs – as did Varda, who studied photography in her twenties before turning to film, and took pictures all her life. In 2021 her family donated all her negatives to the Institut pour la photographie in Lille and it is a treat to see some of this material here. The photos reveal Varda’s early interest in street scenes and in all sorts of unconventional shapes; the latter includes her own body, which she photographed naked when she was pregnant with her first child.

We then move on to Varda’s two big feature successes: Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962) and Vagabond (1985). The former was nominated for the Palme d’Or at Cannes; the latter won the Golden Lion in Venice and triumphed at the box office, selling more than a million tickets (the benchmark for success in France). Varda’s eldest daughter Rosalie, a costume designer on many of her mother’s films, is one of the curators of this exhibition and has contributed many items relating to these and other features. They include, rather wonderfully, the beaten-up leather jacket worn by Sandrine Bonnaire in Vagabond, which follows a fiercely independent and homeless young woman as she roams around the countryside. In the film the jacket seems stuck to Bonnaire like a second skin, so it is jolting to find it here behind a glass case, preserved perfectly, in all its creases, and with a little pin and green thread still attached to the lapel.

Sandrine Bonnaire as Mona in Vagabond (1985). Courtesy Janus Films

In the late 1960s Varda lived in Los Angeles with her husband and fellow director Jacques Demy. The area of the exhibition devoted to this period is colour-coded red, referring to the left-leaning movements Varda depicted in documentaries about the Civil Rights and feminist movements in the United States. Other works singled out include Jane B. par Agnès V. (1988), a film about the late Jane Birkin that is both an intimate portrait and a run of sketches in which Birkin plays different fictional and mythological characters, figures in classical paintings and even a flamenco dancer. There is also Varda’s homage to Demy in the form of Jacquot de Nantes (1991), a fictionalised account of his childhood released a year after he died of AIDS.

Varda by Agnès (2019). Courtesy British Film Institute

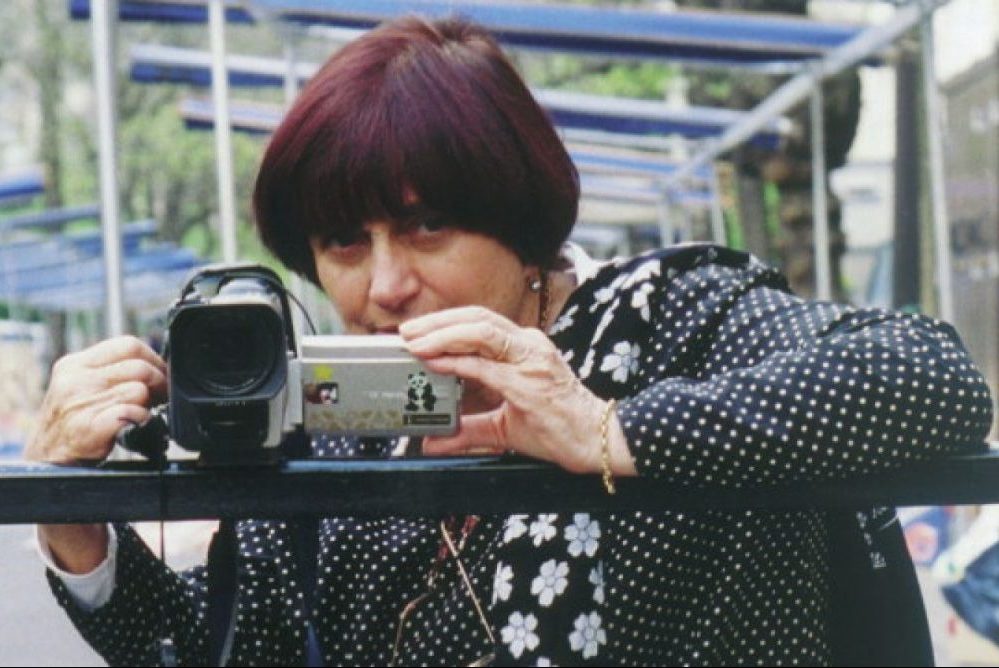

The Gleaners and I (2000) gets its own section; rightly so since it was the film that significantly raised Varda’s profile outside France. Varda explores gleaning, the act of collecting produce left behind after harvesting; in the documentary the focus is on potatoes from a newly dug-up field. But the film is about far more than this, as illustrated by the clip playing in the exhibition. We see here how Varda also captured her first experience shooting with a hand-held digital camera; she muses on how this changed her relationship to the image. She takes a long view of gleaning too, putting it in historical context and juxtaposing her own footage with its depiction by artists such as Millet and van Gogh. To this she adds modern forms of the practice: foraging in bins and abandoned crates on city streets, particularly after markets have closed for the day and before the rejected fruit and vegetables are cleared away.

At the Cinémathèque the film clips appear on flat screens; soundtracks are loud and bleed into each other. The walls are covered with various material from films, photographs, letters, press cuttings and further context from the curators. The lights are bright and so are the colours. It is all very busy, a little messy even, as one imagines Varda’s pink-painted house might have been inside, and the director herself as sociable and bubbling with new ideas. No doubt this is accurate and such an atmosphere is not unpleasant, exactly, but it encourages only one kind of engagement with her work – not the quiet contemplation that it requires.

The final room, however, offers a welcome contrast. Where we might expect a static timeline with dates and key events listed, there is a montage projected on to the wall that runs several metres across, showing photos and video clips from Varda’s life related to feminism and women in cinema. It reveals a more complicated story than we might imagine from the film-maker who made La Pointe Courte (1954), the first feature of the French New Wave, five years before Truffaut and company were hailed as the founders of the movement. The montage shows Varda, at the age of 82, leading a silent protest by a group of actresses and female directors up the famous stairs at Cannes in 2018, and reading a statement criticising the festival’s shameful record of awarding the Palme d’Or almost exclusively to men. But the montage also shows clips from interviews she gave in earlier decades and what emerges here is Varda as an independent spirit, but not necessarily flying the feminist flag. Nor does she seem as fun and lovable as as she does in her late documentaries. The young Varda was above all tough and not always tender. Understanding this as we consider her work is to do her justice.

‘Viva Varda!’ is at the Cinémathèque française, Paris, until 28 January.

From the January 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.