The most famous and influential gallery ever to do business in Los Angeles was Ferus, which, in the 1950s and ’60s, launched the careers of many important artists. There is a widely reproduced promotional photograph from the period that shows seven of them – all white, all men – pressed together like a jolly conga line. Nearly all are now well known (Ed Moses, John Altoon, Craig Kauffman, Ed Kienholz, Robert Irwin, Billy Al Bengston) but one is not. Alan Lynch, who exhibited with Ferus for a short time, slipped into obscurity. Which is how he seemed to want it.

In 2023, Château Shatto, a present-day Los Angeles gallery, took up the representation of Lynch’s estate (he died in 1994) and has been working to bring his work back into the public eye. Earlier this summer it opened ‘Infinitely on the surfaces of this teardrop world’, which wasn’t just the gallery’s first exhibition of his work – it was his first solo exhibition since 1967 and it provided a captivating primer on the artist.

Lynch was born in 1926, and grew up in Los Angeles. During and immediately after the Second World War, he was drawn to the glut of Japanese art and ceramics in the city’s antique stores – the result of Japanese immigrants hurriedly disposing of their possessions before their forcible internment. Lynch’s attention was particularly caught by humble, perfectly imperfect raku ceramics, which he began to collect. He studied other aspects of Japanese culture too, notably Zen Buddhism and meditation, which he would pursue throughout his life, an interest that would eventually eclipse his identity as an artist. Kauffman and Irwin both acknowledged the influence of Lynch’s collection and expertise on them and others in their circle.

Château Shatto’s exhibition began with a display case containing an early oil painting by Lynch and a booklet open at the poem Jack Hirschman wrote about him after his death; it’s from this that the exhibition took its transcendent title. The painting – a nebulous, brushy abstraction titled Bristol Bush (1960) – was ill served by its horizontal capture under glass, since it represents a fertile period of experimentation for Lynch in which inchoate forms emerged through and from his application of paint.

The story really begins in 1962, when Lynch, on a tour through France and Spain, landed on a style of crisply rendered, juicily chromatic biomorphic abstractions. Lynch’s handwritten notebook, in another display case, commemorates the moment: ‘June 26 1962 – Cadaques. Finally yielded to the temptation of hard edge painting. Did two such paintings (overall patterns, rather organic shapes etc.) The results were rather good I think yet it was necessary to destroy them. One could be popular doing this kind of thing.’ Even before he devoted himself wholly to Zen and withdrew from the commercial art world, Lynch evidently had misgivings about conventional forms of success.

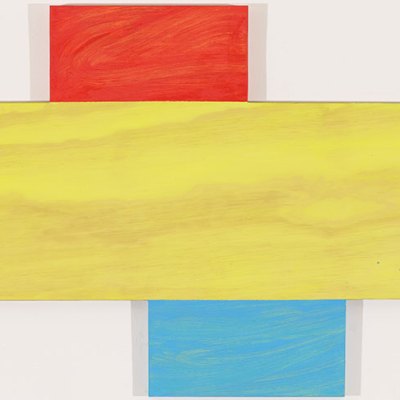

Happily, he got over his reservations, at least for a while. The six oil paintings on canvas assembled here, all made between 1963–65 and hung on mid-grey walls, are perfectly likeable and perhaps did make him popular for a time. In tomato orange and mustard yellow, sky blue and grass green, Lynch painted natural forms redolent of flower buds, stamens and seedpods, cropped tightly as if by a microscope slide. These paintings are fruity in every sense: peachy bum cheeks, plump vulvas, puckering anuses, glandes, breasts and pert nipples are irresistible associations. Inspired in part by the stylised shapes glazed on to his Japanese ceramics, his compositions evoke a happy fecundity and a sense of natural wellbeing.

Throughout the 1960s, Lynch’s career sailed: he had solo exhibitions at the influential Dilexi Gallery in San Francisco and was included in group shows at the Whitney and museums abroad. To me, however, his art fully took flight only in the following decade, after he stopped exhibiting or selling it. From the 1970s on, he devoted himself to Zen studies, eventually being ordained as a monk. His watercolours from this period, such as those presented at Château Shatto made between 1975–77, are taut compositions, none bigger than a postcard, with generous white borders. They are more abstract than his earlier organic forms, with a lustrous glow thanks to his technique of layering washes of colour.

These paintings anticipate the (much later) surreal ink landscapes of Lynch’s friend, the sculptor Ken Price, and may even have influenced Price’s colourful blobby ceramics too. Lynch’s drawings hint at landscapes but, really, they conjure nothing so much as their own phantasmagorical unreality. It is appealing to imagine that Lynch used them as tools for meditation, but they might equally have been the outcome of that meditation – apparitions from the psychic void. We have no way of knowing; Lynch left behind regrettably little writing about his art. In its modest precision, however, it exists outside language and needs little explication.

‘Infinitely on the surfaces of this teardrop world’ was at Château Shatto, Los Angeles, from 31 May–2 August.