From the November 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

The American collector Albert C. Barnes earned his fortune selling Argyrol, a silver-based gonorrhoeal antiseptic that was, according to one British doctor, ‘the best thing we have had since the introduction of cocaine’. Venereal disease gave Barnes an almost limitless market for his invention, which was even prescribed to infants. A few drops in a newborn’s eye prevented ocular infections that might be picked up in the birth canal. ‘With the money acquired from a product which prevents blindness,’ read a 1928 profile in the New Yorker, ‘Dr Barnes purchases pictures for the sight to feast upon’. On the eve of the Great Depression, Barnes sold his business for $5 million, able to plough even more of his fortune into modern art just as many others were forced to sell their own collections. ‘I came back from Europe with the richest plunder ever,’ Barnes boasted.

As Blake Gopnik’s zippy, zesty biography has it, Barnes came from a rough part of Philadelphia called the Neck and had an absent, alcoholic father: ‘I came into the world maladjusted – and I’m still that,’ Barnes wrote. He was insecure and irascible, brutal and sardonic, broad and pugnacious, always ready to sling insults and use his fists. With his newfound wealth, the chemist millionaire armoured himself in Savile Row suits and fast, stylish cars. He also built himself a mansion called Lauraston on Philadelphia’s Main Line, the gilded suburbs that sprung up along the railway west of the city. Barnes called on his best friend from high school, the artist William Glackens, who had cofounded New York’s Ashcan school of socially conscious painters, when he was looking to buy art to decorate its walls.

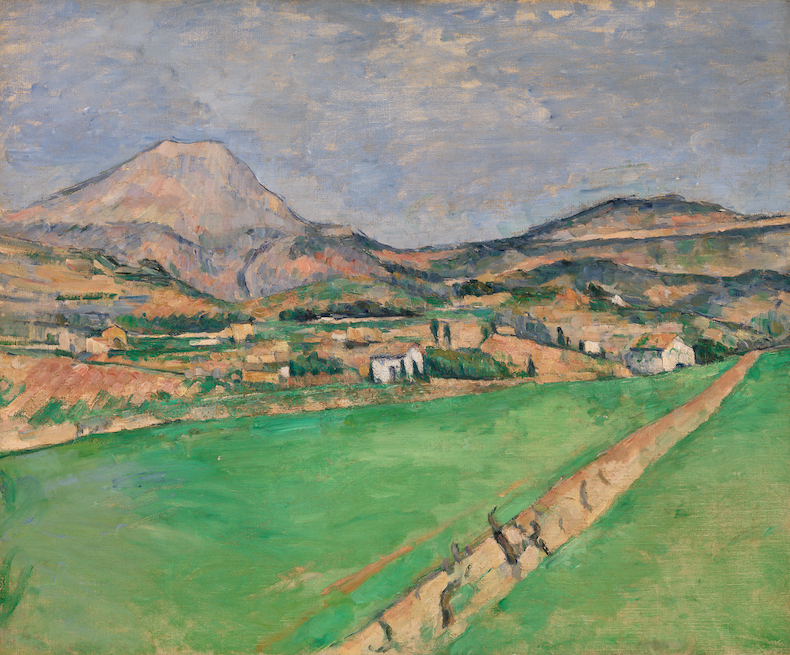

Instead of the Dutch landscapes and British portraits favoured by his neighbours, Barnes started collecting the Ashcans as a way of supporting his friend and circle. In 1912, Glackens was dispatched to Paris with $20,000 in cash to be an early American buyer of the radical European art that the Ashcans held in such esteem. Glackens befriended Leo and Gertrude Stein, who were his aesthetic guides to the city, and acquired Van Gogh’s Postman (1889), the first work by the artist to reach the United States, along with 32 other works by artists including Cézanne, Renoir and Picasso. The next year, Barnes followed him to Europe, waving ‘his chequebook in the air’, according to Gertrude Stein, who sold him two Matisses. Barnes spent $60,000 in a week and at one Parisian auction bid so much for Cézanne’s Five Bathers (1878) that ‘derisive laughter’ broke out. In 1920, he acquired 13 more works by the artist that had been on loan to the Rijksmuseum, including an impressive painting of Mont Sainte-Victoire.

Buying art had become an obsession – Barnes compared his collecting bug to having rabies – which gave meaning to his rich but empty life. He said that looking at the fleshy Renoirs he owned (he had a penchant for nudes) helped to dissolve his ‘damnable’ psychological complexes. In 1917 he audited a class at Columbia University by John Dewey, and the philosopher’s ideas of pragmatism, which prioritised experience over theory, gave further rationale to Barnes’s shopping. The two became firm friends and Dewey was a frequent visitor to Lauraston, whose every surface was now crammed with art. Barnes’s Argyrol factory became something of an educational experiment in what Dewey called ‘Art as Experience’. It was decorated with more than 100 paintings, even in the rest rooms, and Barnes introduced two hours of humanist discussion into the workday to ‘awaken’ his employees’ aesthetic lives.

Barnes employed a majority of Black workers in his factories and was a vocal champion of Black culture. He thought that ‘ancient negro art’, of which he amassed a large collection, was ‘equal to the best of ancient Greece and Egypt’. He found in it the stylisation and rough, simplified forms that he admired in French art, and was aware of the ways in which France’s colonial loot had inspired that avant-garde. Gopnik is cynical of Barnes’s support for Black rights, dismissing his European Primitivism and paternalistic attitude, though ‘real … and heartfelt’, as largely rhetorical.

In 1925 Barnes opened a museum to show his 600 works of modern art – among them 150 Renoirs, 50 Cézannes, 22 Picassos and 12 Matisses. He wanted a house museum like the Wallace Collection, and the result was a surprisingly staid Beaux-Arts structure, the interiors of which were domestically scaled, with small rooms and high windows that illuminated his paintings from above. His foundation put Deweyism into practical effect (Barnes later also became a patron to Bertrand Russell, who lectured there). Jacques Lipchitz was commissioned to do cubist basreliefs on the exterior and Matisse to paint a huge mural, The Dance, inside. Barnes quickly added Odilon Redon, Giorgio de Chirico and Amedeo Modigliani to his collection, as well as numerous African works, and expensive trophy paintings including Seurat’s Models and Cézanne’s Card Players. This was a decade before the Museum of Modern Art, and indeed its founding director Alfred Barr was a 24-year-old pilgrim to ‘the finest collection of modern painting in America’.

Barnes was a strict formalist, interested in aesthetic immersion and microscopic analysis over narrative and iconography. He was an advocate of slow looking: ‘Art appreciation can no more be absorbed by aimless wandering in galleries than surgery can be learned by casual visits to a hospital,’ he warned. Visits to his museum were only by appointment and, even then, the eccentric, dyspeptic proprietor would insist on giving a lecture and might eject you for admiring art in ‘incorrect’ ways. As a result, his stellar collection went largely unseen. Barnes died in 1951.

In 2012, despite a vigorous campaign by the Friends of the Barnes Foundation, the institution moved to a sleek, new campus near the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The interiors replicate the old museum, with its unusual juxtaposition of paintings and antiques – a collection estimated to be worth $25bn.

The Maverick’s Museum: Albert Barnes and his American Dream by Blake Gopnik is published by Ecco.

From the November 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.