Owen Hatherley’s new book is ‘The Alienation Effect: How Central European Émigrés Transformed the British Twentieth Century’ (Allen Lane). The book, which looks at the fields of photography, film, publishing, art and architecture, is about the intellectuals who escaped fascism in Central and Eastern Europe in the 1930s and came to Britain. Not all of them stayed, some preferring to move to the United States, but those who did changed the cultural life of the country in radical ways and many were, in turn, changed by what they experienced in Britain, including internment during the Second World War. Fatema Ahmed talks to Owen Hatherley about the fascinating figures in his book and the challenge of writing cultural history on such a scale.

Fatema Ahmed: Anyone looking at the long list of your earlier books can see the strands that have gone into this one: you’ve already written about Central Europe and about Britain in the 20th century. But what possessed you to write about both – and about so many different figures and different art forms – in a single book?

Owen Hatherley: My first instinct is to go to the honest answer. The stuff that I do a lot of the time – walking around describing things – is quite easy to do. Iain Sinclair once said that Chris Petit had just told him, ‘Well, you walk around and you describe what you’ve seen, don’t you?’ It’s obviously not quite as simple as that, but there is an element of half the job being done when you’ve done the walking. I wanted to see if I could do a history book where you didn’t have to be particularly interested in the built environment, you didn’t have to be particularly interested in me, and where you could try and run together lots of different art forms and see the ways in which they connect.

The subject matter is a much easier question to answer because it came out of my irritation with a specific book (and, if I mention it, I want it on record that I’ve liked a lot of other things he’s done), which is Bauhaus Goes West by Alan Powers. There’s a dual thing going on in that book where, on the one hand, he suggests that maybe interwar British culture wasn’t totally insular. But I think he gets bored of that halfway through – because you can’t justify that position – and then goes, well, does it matter that it was backward at all? And I think you have to make one argument or the other. I was reading that book when I was writing Modern Buildings in Britain and trying to contextualise in the introduction modern architecture in Britain and how it came here. I went into it not really knowing what position I would take on the émigrés and the more I was reading, the more I realised that, without them, Britain would really have remained a backwater.

The subject matter is a much easier question to answer because it came out of my irritation with a specific book (and, if I mention it, I want it on record that I’ve liked a lot of other things he’s done), which is Bauhaus Goes West by Alan Powers. There’s a dual thing going on in that book where, on the one hand, he suggests that maybe interwar British culture wasn’t totally insular. But I think he gets bored of that halfway through – because you can’t justify that position – and then goes, well, does it matter that it was backward at all? And I think you have to make one argument or the other. I was reading that book when I was writing Modern Buildings in Britain and trying to contextualise in the introduction modern architecture in Britain and how it came here. I went into it not really knowing what position I would take on the émigrés and the more I was reading, the more I realised that, without them, Britain would really have remained a backwater.

There’s a great Evelyn Waugh line about John Betjeman where he says – and I don’t completely agree with him – that all the stuff that Betjeman writes about is basically rubbish and second rate. This only happened because of the Second World War and the austerity that followed, meaning that the English middle classes could no longer go to Italy and France and see actually good architecture. Instead, they had to construct these cults around quite some second- and third-rate architecture. It’s unfair, but it has an element of truth. And I think a lot of that has happened again in the last 10 years. Not that people haven’t left, but they’ve left less often. There are certain times in British history where the channel becomes a wall. The last 10 years is one of those times and the 1920s was also one of those times. The reaction to the First World War was a wave of nostalgia and xenophobia and insularity. It really is one of the most culturally barren decades in Britain – in a way that really contrasts with so much of what was happening on the continent, particularly in Central Europe. The reason it was missed was partly because of that insularity and partly because it was coming from a place where British intellectuals didn’t usually look.

Britain just sits out this moment and I find that really interesting to think about. So the book started with that, rather than thinking about migration and the émigrés themselves. It came out of trying to answer that conundrum.

You talk about Britain in the interwar years, but you are also very good at conveying just how much turmoil there was in Central Europe in the same period. You are often writing about double refugees, people who’ve left at least two countries before getting to Britain. And, in terms of history, while everyone’s heard of Weimar Germany that’s not true of, say, the Hungarian Soviet Republic.

So many of the people who are habitually described as Hungarians in Britain – rightly so, because they were born in Hungary and their first language was Hungarian – were Hungarian Jews who had left after the suppression of the Soviet Republic in 1919, which was followed by a wave of antisemitic violence. Some of those people were genuinely quite involved with the Republic, like Stefan Lorant. Some people are more like collateral damage, like Emeric Pressburger. They all then cut their teeth in Berlin. Sometimes there are triple migrations. People like John Heartfield go: Berlin, then Prague, then Paris and London. That’s quite common, those cities and that order. Naum Gabo is a complicated one because he went from the Soviet Union to Berlin, Paris and London.

It’s a story about revolutions and counter revolutions. There is the revolution that happens in St Petersburg in 1917, but there’s also the more abortive one that happens in Berlin and in Munich and Hamburg a few years later. There’s the one that succeeds for a while and is then bloodily suppressed in Hungary. These lead to regimes that aren’t really talked about a lot. [Apart from Czechoslovakia,] they were all authoritarian, right-wing antisemitic dictatorships before 1939 and that led to a kind of artistic diaspora.

But while this is all going on, Britain – whatever its relation to modernism and however unequal – is politically settled. Arthur Koestler, writing in the 1950s but looking back to the ’30s, describes Britain as ‘a kind of Davos for the internally bruised veterans of totalitarian age’. One of the important points you make is that few figures in the absolute first rank of modernism actually wanted to stay; they left for the United States if they could. Gropius left; Kurt Schwitters is a very tragic figure in the book. What was it about Britain that did and didn’t appeal?

Gabo is the other actual first-rank figure who stays for a long time. Even though he does then go to the States, he had a good long run here and was quite influential here. Schwitters wasn’t [influential] until after his death. It’s as if there are three categories. There are the greats, who are famous where they’ve come from – and are very shocked by how not famous they are when they arrive. There are degrees of that: Gropius actually does have a welcoming party and there are quite a lot of people that surround Gropius telling him he’s wonderful – though never as many as there would be in the US.

There’s another category of people who are very young, like Isi Metzstein, the architect, and Karel Reisz, the film-maker. To all intents and purposes they’re British architects and British film-makers, it’s just that they carry that memory of escape and refuge with and often carry the fact that they had to learn a new language with them.

Then there are those who arrive as moderate successes: people that have published a book or two, done a few paintings, designed a few buildings, such as Berthold Lubetkin, Hans Feibusch, Ernö Goldfinger and Nikolaus Pevsner. They’re in their 30s, they know people – Goldfinger knows Le Corbusier; Pevsner knows Gropius – but they’re very much the second-rank figures. They come in with these modernist ideologies, which they’re very strongly committed to, but no one in Harvard is going to offer them any money, and they spot an opportunity. They realise that they can be the great modernist magus.

The Koestler thing about Davos: there’s a particular group of people who really are committed to Englishness and English values as they see them, which are generally conservative, free market, mother of parliaments: Friedrich Hayek, Karl Popper, Ernst Gombrich and Koestler himself, who, for a lot of very good reasons, moves very sharply to the right when he moves to Britain. They arrive and they tell Britain what it wants to hear. The people who most interest me are those like Pevsner, who obviously find something they like in Britain, or they wouldn’t have settled here. They like the stability but there is very much a feeling of: ‘You’ve got to pay attention […] you can’t live forever in this Edwin Lutyens mock-Tudor dream world.’ The war led to a lot of people agreeing with them. The experience of the Depression and the war together meant that in 1945, they had a kind of captive lower-middle-class, Penguin Books-reading audience that they didn’t have in the ‘30s. And in some ways they created that audience through the revolution at Penguin and through Stefan Lorant creating Picture Post.

Can you explain to people what Picture Post was?

I suppose the easiest thing to say is that it was the British LIFE magazine. But it was also modelled in large part on German journals, which Lorant had edited, such as Münchner Illustrated Zeitung – one of the biggest circulation weeklies in Germany. It was a funny thing because it was an attempt to make something that was American and was also German, but the content was absolutely obsessed with Englishness. That came out of Lorant’s own proclivities. He really did find it fascinating in its eccentricity and strangeness. It also came out of the fact that the photo agency they used was set up by a Hungarian. About 90 per cent of their photographers through most of their history were German or Austrian or Hungarian.

A lot of people that don’t think they know Picture Post will see the photos and go, oh yes, that: pictures of Blackpool, the East End, the Gorbals, the north of England. Lots of very famous images from the ‘30s and ‘40s are taken by these people. There’s initially a duo of Kurt Hutton and Felix Man and Lorant just brings them with him. He says, you are going to get into big trouble if you stay in Nazi Germany. There’s a slightly later generation of people that are much more avant-garde and politically committed. People like Bill Brandt, who was very much a Surrealist and was from Hamburg – which he kept secret: he didn’t like to be seen as German. Then there were people from Austria who were from Marxist backgrounds, like Edith Tudor-Hart and her brother, Wolfgang Suschitzky. Tudor-Hart was an NKVD spy on the side. Suschitzky later goes off and films Get Carter (1971).

Picture Post had big crusades in favour of the welfare state, in favour of planning, against appeasement of Hitler, in favour of the Spanish Republic. Although it wasn’t an explicitly left-wing paper, it was very much a campaigning, centre-left paper. The photographs were designed to be used in that.

Barmaids’ Rest Hour by Bill Brandt: Barmaids, Ivy (left) and Alice, reading in deckchairs during their rest hour, on the roof of The Crooked Billet pub in Tower Hill, London, 1939. In the background are Tower Bridge (left) and the Tower of London. Original published in ‘A Barmaid’s Day’, Picture Post (345), 8 April 1939. Photo: Bill Brandt/Picture Post/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The status of photography in Britain at the time is not unlike that of modern architecture. The British were in on it from the start, but it’s not taken seriously as an art form.

There are a lot of examples of this throughout the book. Modern architecture is one of them: as Pevsner points out in Pioneers of Modern Design, his most influential early book in Britain, a modern movement in architecture involves the technologies of the Crystal Palace, the aesthetics of early industrial factories. Apart from modern painting and cubism, almost all the influences on the modern architecture that develops in Central Europe are British. Britain does not really have its own version of it until Central Europeans bring it over.

Pevsner is one of the most important figures in the book. He was an art historian who developed important series of books for Penguin, who is better known now as an architectural historian – the Buildings of England series has become an architectural bible. How do you think about his achievements in the round?

He basically says: English art is irrational and unclassifiable, and therefore I’m now going to classify it. The ‘Englishness of English Art’ [the title of a famous essay] is in many ways quite doomed, but hugely influential on people such as Ian Nairn. It’s trying to systematise this thing that has no system, which is a great intellectual game to play. The particular kinds of English culture that a lot of the émigrés get interested in is quite telling. Hogarth is quite popular. They really think they’ve found something quite unusual with Hogarth, not just as a satirist but also for his sophistication as a painter. They tended to think of British painters as dreadful; Hogarth is the exception.

Your liking for the films of Powell and Pressburger shines through. I was particularly struck by your discussion of the trial in A Matter of Life and Death taking place in a kind of ‘Bauhaus Heaven’. What do you mean by that?

The designer on that, Alfred Junge, was one of the many émigrés working for Powell and Pressburger. There were a lot of public buildings that looked like that in 1920s Germany and they tended to be hospitals, social housing, quite welfare-state-y buildings. It’s partly a joke on modern architecture, but I think it’s also quite sincere. The bureaucracy in the film isn’t totalitarian, it isn’t evil. It’s bureaucracy and it acts like bureaucracies tend to: in many ways, I think it’s quite benign. It’s a vision of the sort of societies that a lot of these people thought they were building. I like the fact that Pressburger apparently kept a load of Bauhaus furniture in his home, in his office. He chose to live like this.

To go back to your categories of people, as well as people who are already famous and the people who become more famous, there’s also another kind of person who is not at all well known. Some of the artists did a surprising amount of work for churches. Can you talk about this phenomenon?

I encountered a lot of these people through the Insiders/Outsiders Project by Monica Bohm-Duchen, which was highly useful to have around while I was doing this. I started writing my book before that exhibition and book came out and a YouTube channel, which spiralled off it. A lot of the less famous, often slightly more conservative people – I came across them through that project. There are some people you’ve not heard of and then you find that they’re everywhere. Naomi Blake is one of them. Her sculptures are absolutely everywhere, a strange combination of figurative and Hepworth-esque. They quite explicitly comment on trauma and mourning, and so on. Hans Feibusch is another – you suddenly find that he’s absolutely everywhere.

The church thing is a combination of the deliberate and accidental, like a lot of these things. The deliberate part is George Bell [the bishop of Chichester]. The accidental part is that, because of the expansion of council housing, there’s a load of new churches being built. The commissions go to who’s working at the time and a lot of those people are émigrés. Often they’re atheist or Jewish émigrés designing for new council estate churches, which are never going to have a big congregation, which are frequently now empty and unused because they were built at a time in which the church was just about to disappear from people’s lives.

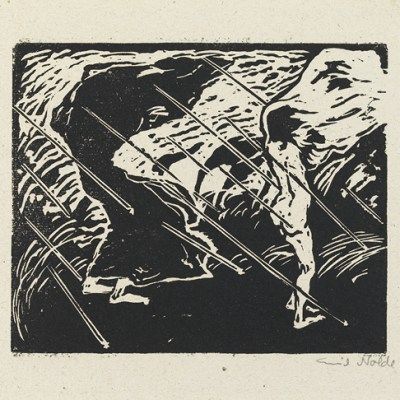

I can’t not mention Apollo’s review of the ‘Exhibition of Twentieth Century German Art’ which took place in London in 1938, a year after the Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich. This show is not as well-known as its notorious predecessor, so how would you describe it?

It’s at the Burlington Galleries, a private gallery not far from the Royal Academy, which was the progressive gallery at the time; it had its first show on Surrealism, it had a lot of the first shows of modern architecture. [The critic] Herbert Read and the émigré curator Edith Hoffman came up with this idea to do a direct response to the Degenerate Art exhibition, which pillories all of the modern art of the late imperial and Weimar eras. Importantly, [the Nazis] were able to do this because the Weimar Republic built up incredible modern art collections. There was nothing like that anywhere else – maybe the Soviet Union a little bit, but nowhere else where actual state institutions were collecting modern art at that point. That meant that when the Nazis took over they had the right to do what they liked with this enormous modern art collection – and what they did was put it in the stocks and invite people to jeer at it.

[Read and Hoffman] were quite politically careful. They didn’t try to be too explicit, for diplomatic reasons, because they didn’t want to get closed down and they didn’t want violence. But the goal was to show people this art and try and convince them that it was good. Also, in Read’s case – and I don’t think a lot of émigrés were really down with this particular project – the aim was also to show British artists: this is the sort of art you should be doing. Because these people are like us. We do not live in Provence or Tuscany. We do not have that light. But north Germany looks quite a lot like the Midlands. Read was from Leeds and I think he saw a lot of German Expressionist painting and was like, ‘Why aren’t we doing this?’

Apollo’s reviewer writes: ‘German art suffers, it would seem, most from “bad form”. Like the German language itself, it lacks clarity. It is continent both in its furor, the furor Teutonicus, and in its sentiment – its Schwärmerei.’ Not a fan then.

It’s violent, it’s unpleasant. [People] saw it as this really violent, polemical, deliberately ugly art and completely rejected it. This had major consequences for people like Schwitters. He basically stayed alive in the Lake District after the war on a stipend from the Museum of Modern Art. No one here really knew who he was.

I’ve darted around a bit because I wanted people to get a sense of how much ground you cover. When you mentioned wanting to write a proper history book, it reminded me of the kind of synoptic histories that some of these émigrés were responsible for and championed to get published.

I really like that particular style of history writing where rather than [someone saying] I am going to concentrate on this one small thing and everything about it, they do these quite intricate books about historical interconnections. I only mention Eric Hobsbawm a couple of times in the book, but Hobsbawm was a big thing for me when I was writing it: the Age of quartet, which reviewers on the left very much saw as a waste of time for Hobsbawm to be writing. But I love those sorts of books and you can follow them, if they work, into the more specific highways and byways. A lot of those émigrés – Hobsbawm, Gombrich, Pevsner in particular – created these huge maps to subjects that people didn’t know much about. That was very much at the back of my mind.

Were there any subjects or people you didn’t know much about before that you were pleased to discover?

The thing I most enjoyed, which surprised me, was the book-publishing end of it and finding that émigrés are everywhere. There’s something quite fun about going into second-hand bookshops and finding that this thing is everywhere, that it was such a mass-market thing, even though the people involved were largely intellectuals from quite rarefied backgrounds. They were really into this idea of mass communication.

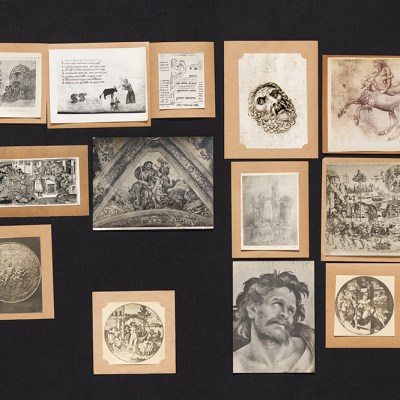

Inside Newport Civic Centre, The History of Newport, a series of murals designed by Hans Feibusch and painted by him and Phyllis Bray in 1961–64. Photo: Owen Hatherley

You have a line towards the end that, regardless of their specific politics, the figures in your book all believed in ‘public culture and public luxury’. That’s something you clearly believe in, too, but it’s vanishing, if it hasn’t already gone?

I tried quite hard not to bring in too many contemporary resonances. I wanted to be read by people who disagreed with me. Then, at the end, I felt, if there’s anything all these people were absolutely against – with the exception of Hayek – it’s laissez-faire and austerity, this idea that the market dictates. That was pretty universal, with that one very big exception, whether they were liberals like Gombrich, or communists or socialists like Josef Herman. They very much believed in communicating with a public, they believed that it was the role of government to provide for that public and that the role of artists and intellectuals was to get in there.

Right at the end I wanted to come up with somewhere, a place, of which I could say: this is everything we’re currently lacking. And that was Newport Civic Centre, which to my mind is by far the best of Hans Feibusch’s murals of Britain, because it’s not Christian. They’re just this fabulous work of abundance and generosity in a place where – you can’t walk around Newport and not see how much it has been screwed over in the last few decades. It’s a completely different way of seeing the world, the state, the community, the city, than the one that is being rammed down our throats by all of the main political parties and the media that serves them. I couldn’t resist right at the end expanding out, but mostly I tried not to.

The Alienation Effect: How Central European Émigrés Transformed the British Twentieth Century is published by Allen Lane.