You don’t so much enter a building designed by John Soane, as submit to it. The eccentric Regency architect used light and colour as others less capable in the field did mere brick and stone, and at Pitzhanger Manor, the country seat he created for himself at Ealing in 1804, they mould the interior to magical effect.

A new exhibition at Pitzhanger pairs Soane – man and work – with the contemporary Scottish artist Alison Watt, whose meticulous still life paintings share not just his particular regard for light, but the quality his architecture had of being all the grander for its reticence.

The opportunity to reflect on a possible like-mindedness between the two artists is a rewarding and intentionally poetic one. ‘From Light’ is the show’s title, but it embraces other harmonies besides, such as absence, and history, memorialising and memento mori. Watt is attuned to the memento mori in a way that’s rare for this era.

Installation shot of Roman (2024) and Vanitas (2024) in the Small Drawing Room. Photo: Andy Stagg

The display is divided into two chapters: one in which Watt’s paintings have been placed in dialogue with the house proper, the other in the part of the site that since 1996 has functioned as a gallery for contemporary art. Watt is unaccompanied here, and this is where the exhibition begins.

What’s in the paintings then? On first looking, not much. White cloth, blank paper, a teacup, flowers, a porcelain cherub’s head. Suspended in plain, unmodulated grounds they feel self-contained, mute, ice-cold. Watt manipulates paint with dizzying skill, but if that and the range suggests an academic exercise, wait a little. Very quickly, the work’s formality is subverted by an oddity that edges into the surreal.

Consider the paintings of white linen. There are five of them, the cloth variously folded, hung, flapping with a mind of its own. There are irrepressible, uncontainable things beneath their forms. Glanville (2022), Holland (2021–23) and Pendant (2024) retain the impression of table edge, but no table. Of course they look like ghosts.

Glanville (2020–22), Alison Watt. Courtesy Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery; © the artist

Facing them is a quartet of rose sprigs, pink and mouthwateringly pretty. Or so it seems: in a wall text, Watt explains that ‘in the history of painting, the rose can be read as a symbol of beauty, innocence and transience, but also decline and decay, echoing Soane’s preoccupation with themes of death and memorialisation’ and so it is here, petals yellowing, leaves spotted, the roses overblown and on the brink of rot.

The exhibition’s saturnine complexion peaks in the adjoining room, where three theatrically lit paintings of a death mask hang on the far wall. Beautiful in their play of light and shadow, the plaster a subtle flux of greyish, blueish, brownish whites; they make for eerie, intoxicating viewing. Variations in Watt’s vantage point give the face an oddly kinetic feel – as if it were some kind of ghoulish stop-mo or flip-book animation.

Installation view of Parker (2024), by Alison Watt, Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery. Photo: Andy Stagg; © the artist

Soane – a famously omnivorous collector – bought the mask thinking it the face of the failed mutineer Richard Parker (captured, tried and hanged in 1797) though it turned out to be that of Oliver Cromwell. The three iterations, a wall text tells us, are meant to echo Van Dyck’s triple portrait of the Parliamentarian’s arch-enemy, King Charles I.

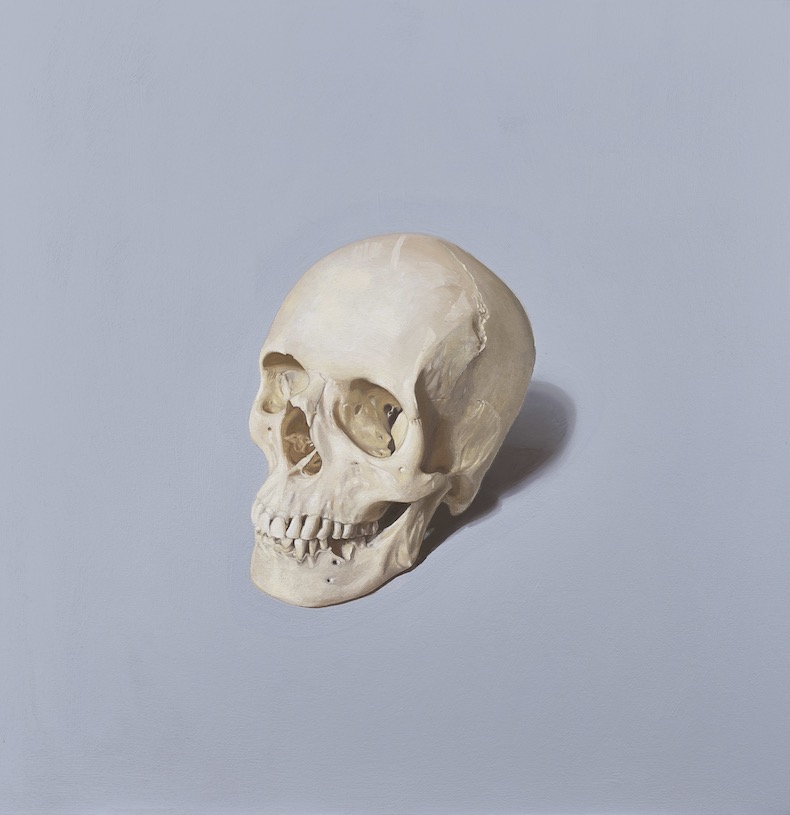

The show continues in Soane’s breakfast room, where objects from Watt’s Edinburgh studio are displayed in the niches he designed to showcase prized pieces from his own collection. A trio of skulls (real, cast, drawn), a close-up painting of an eye. It’s a meeting of two minds across the centuries, a meditation on art and history and, like the opening of a brilliant play, whets the appetite for the acts that follow.

Soane’s breakfast room, where objects from Watt’s Edinburgh studio are displayed in niches. Photo: Andy Stagg

Wander from here into a library, conservatory and a small drawing room, and the show begins to acquire the feeling of a treasure hunt, or an intellectual puzzle in which the riddles get more surreal. Watt’s paintings here are of Soane in absentia; the figure no longer present, only implied.

Vanitas (2024) refers to the skeleton that Soane was given by the sculptor John Flaxman, for instance. Roman (2024), meanwhile, isolates a quill from the background of a portrait of Soane by William Owen that hangs today in Soane’s London townhouse at Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

Vanitas (2024), Alison Watt. Courtesy Pitzhanger Manor & Gallery; © the artist

There is no set route here, or heavy-handed wall texts. It’s easy to lose sense of where you are, in fact, and much of the exhibition’s pleasure is in succumbing to that. To stumble across Watt’s paintings, rather than trudging compliantly from one to the next, is sweet every time.

In the Upper Drawing Room, you’ll see too that her pastel blue and green grounds are borrowed from its Wedgwood-style geometric ceiling, and that Le Ciel (2024), of a white rosebud on a leafy stem, mirrors both the hand-painted wallpaper on its walls and the blitz of real green framed by the large windows in the Georgian Eating Room downstairs. Wherever you turn, in fact, whichever route you follow through the house, Watt and Soane – present and past – seem to be in conversation. There’s an eeriness to that, but also real beauty.

‘Alison Watt: From Light’ is at Pitzhanger Manor, London, until 15 June.